Shinto

Part of the Suwa Grand Shrine, a venerable Shinto institution that is very relevant to the Lore of Touhou.

Numerous Touhou fans have made a pilgrimmage to there.

Shinto is the term that is most commonly used to refer to the indigenous religion of Japan. However, the term Shinto is somewhat controversional, even and perhaps especially in Japan. Some see Shinto as an organic continuation of ancient spiritual traditions that first started to be formulated from the 5th century onwards as a response to spread of Buddhism. Others see it as a 19th century invention built to support imperial nation-building attempts, enforced at the cost of supressing local, organic traditions. Perhaps Shinto is bit of both, shaped by both tension and harmony between the imperial and local, the central and the peripheral, the modern and the ancient. I have chosen to go with Shinto, as it is the most established term.

Shinto has been variously described as an animistic religion, tradition or worldview. Many in Japan dislike Shinto being called a religion. Partly this is due to cultural and historical baggage. Before the arrival of Christianity, the Japanese didn’t really have a term for religion, and they associate ”religion” heavily with Christianity and monotheistic ideas. The term has later also acquired cult-like connotations. Furthermore, during the era of State Shinto, Shinto was not defined as a religion to circumvent laws regarding religious freedom, and this likely has contributed to the idea that Shinto isn’t a religion up to this day.

Another reason for the hesitation to label Shinto a religion is due to how Shinto lacks some common Western characteristics of a religion, lacking a singular founder and definitive body of holy texts. A third factor why some do not see a Shinto as a religion is its extreme focus on doing things rather than belief itself. So while in the West many identify as Christian but never go to the church, in Japan many don't consider themselves religious at all yet attend all the core matsuri (Shinto festivals) and visit the shrines.

Whatever Shinto might be, it’s at least extremely culturally influential in Japan to this day. One can find shrines of all sizes and shapes even at the heart of modern cities, and it’s worldview still impacts people. Touhou’s treatment of the Japanese spiritual traditions that can be justifiably called Shinto is notable in how central part it forms the worldbuilding and lore, and how the various internal tensions and conflicts are repsented within the games and printworks.

Shinto representation in Touhou

Influence from ideas, beliefs and mythology that are featured in Shinto saturate all of Touhou. Our red and white default protagonist is a shrine maiden (miko) taking care of a shrine (jinja). While in real life the miko mostly work in assisting roles to the priests (kannushi) and perform certain rituals, Reimu seems to be stuck taking care of the Hakurei shrine by her lonesome. ZUN, curiously enough, calls himself ”the Kannushi of Hakurei shrine”. The two of them apparently have some kind of an unique arrangement where ZUN takes care of shrine business in the outside world and Reimu in Gensokyo.

While miko do not ”exterminate youkai” in real life, youkai in itself are part of the Shinto view of the world. Youkai are strange spirit creatures of ambigious but often fearful and hostile nature. They are often thought to be spirits that could not be successfully appeased or who became irreversibly scorned. The category of youkai is fluid: youkai can turn to kami, kami can turn to youkai, humans can turn to youkai and not all youkai are hostile. And while the miko may not be flinging iron needles or ofuda at youkai in real life, historically Shinto purification rituals were thought to keep youkai at bay.

The Hakurei Shrine is not the only Shinto institution in Gensokyo. There is also the Moriya Shrine, the important characters within there drawing heavily from the lore of the Suwa Grand Shrine, a very real, very old Shinto shrine. The Aki sisters, Hina-sama, Keiki-sama, Chimata-sama and many more are all based on Shinto deities or amalgamations of them. The lore connected to the Moon and Lunarians features many Shinto kami very prominently. There's even a shrine dedicated to the extremely popular real-life Inari Ookami in the Human Village. Touhou's idea of fairies who are born and reborn with natural cycles and who represent various natural phenomena is also very much in line with Shinto thinking.

Going over every single reference in Touhou to something also found in Shinto is not practical, so instead I will introduce some core features of Shinto and highlight their connection to Touhou when aproriate.

Tama, mi and mono, spiritual power entangled with the material

There are several words in Shinto for what in West could be called spiritual power: tama, mi and mono. Tama is a type of spiritual power that infuses the material world, while maintaining both the integrity of itself and physical matter. This makes tama somewhat similar to Western ideas of ”soul” or ”spirit”. An analogy of beach sand suspended in seawater can be used to describe tama. Here tama is the seawater, and matter the sand: the sand might be completely immersed in the seawater, yet does not dissolve in it.

Mi and mono refer to a type of spiritual power that is intertwined with materiality. Matter does not exist without mi or mono, and mi and mono do not exist without matter. An analogy of seawater is useful again here, but this time it is of water and salt. Salt dissolves into seawater, and seawater is salty everywhere. Mi and mono are subtle and easy to overlook, and Shinto praxis aims to sensitize the practitioner to this spiritual aspect of reality.

Sometimes however, the mi becomes something that starts to move on it’s on and call attention to itself, becoming more tama-like, developing an integrity of it’s own. It moves within the physical world but does not fully disappear into it, developing into an individual ”soul” or ”spirit”. These are called mitama or tamashii in Japanese. They can refer both to individual souls or something collective. Yamato damashii, ”the japanese soul” as an example of collective tamashii.

Mono can have a meaning of it’s own. It can refer to a kind of changeling spiritual quality that moves among the forms of ghosts, monsters, animals and humans. Much like mi, mono too can become particularized enough to resemble tama. This kind of mono is particularly manifest in cases of spirit possessions.

The Japanese use tama, mi and mono in ways where they blur together, and it’s possible to view them as modes of being rather than sharply delineated categories of their own. These modes of being are manifest in how things are related. Tama is spiritual power in reference to external relations, while mi and mono are spiritual power in reference to internal relations.

A mundane example of external relations would be a bridge over a river connecting two roads. Remove the bridge, and the connection becomes severed, yet the two roads and the river would continue to exist. Internal relations are such that severing them changes the nature of the related things. The human body and it’s organs can be used as an example here: the organs cannot survive the body, and the body cannot survive without the organs.

So to sum up these concepts, in Shinto, the spiritual is deeply enmeshed with the material world and manifests in relational ways. The spiritual can manifest and be felt in many different ways, and one way for it to manifest forms a very particular concept in Shinto: the kami.

The kami

At the heart of Shinto are the kami, which is a concept with no direct translation. It appears to be variously interpreted as the felt presence of spirits of things, or just a kind of awe-inducing quality that things possess, but sometimes as more discrete and autonomous entities. In Shinto, due how the spiritual saturates all of reality, there are an innumerable amount of kami: a tree can be a kami, a revered object can be a kami, a human can be a kami, a force of nature can be a kami, and there is even at least one case of a fictional character becoming enshrined as a kami. Some kami are very abstract or local, such as the land kami of a single house. Some however appear to be closer to gods in many other religions in how they are portrayed. The Shinto mythology is full of human-like, but immensely powerful, kami living out drama reminiscent of many other polytheistic religions.

In Shinto, the kami are divided in three categories: the heavenly amatsukami, the earthly kunitsukami and myriad kami yaoyorozu no kami. The amatsukami and kunitsukami are described as human-like, but mythical and powerful, occasionally representing archetypal primordial forces. Various lines of interpretation exist for what exactly they are. A common interpretation is that the amatsukami are the mythologized forefathers of the imperial Yamato lineage, and the kunitsukami are forefathers of people the Yamato conquered or assimilated. The Japanese creation myths are after all in part a story of the conquest of the kunitsukami and the pacification of the land. Some however interpret the amatsukami as kind of celestial, cosmic deities and the kunitsukami as terrestrial deities, and view the conquest in more metaphorical terms. Thus the story of the amatsukami and kunitsukami is not to them of Japan’s origin, but of all humans on Earth.

In contrast to the amatsukami and kunitsukami, the yayorozu no kami or myriad kami are not usually depicted traditionally as human-like, in fact, there’s very little time spent describing them in itself. This is because the ”eight million kami”, signifying infinity, are ominpresent, in every place and every thing. As such, the myriad kami include things such as the kami of a door or the kami of a cucumber. Thus it’s thought that all things should be treated with respect to ensure their proper function. Over time a yayorozu no kami can become more powerful and individuated, such as in the legends of tsukumogami where beloved items acquire a more individuated presence of their own, becoming animate. This concept is referenced in multiple places in Touhou, but especially the game Double Dealing Character.

The kami are neither evil or good by nature, but rather have both a gentle (nigimitama) and a rough (aramitama) side to them. A rain can water the crops or bring a devastating flood and the sun can sustain life but also destroy it via droughts. Furthermore, it’s thought that kami also have a ”happy” (sachimitama) nature and a ”mysterious” (kushimitama) nature that emerge when the relationship with kami is good. This idea is known as the ichirei shikon, or one spirit, four souls. Shinto practitioners see these features also manifest in humans (as we are also considered at least potential kami), and some ascribe all kinds of potential effects to imbalances of these natures within people or things.

As the concepts of sachimitama and kushimitama suggest, in Shinto it is thought that it's possible to cultivate a relationship between humanity and the kami where the kami become favorable to humans. This is done via various rituals, offerings and prayers. Over time the relationship between humans and kami can become such that it's possible to ask the kami for favors.

An example of this process is the myth of Tenjin, the kami of scholarship. He was originally Sugawara no Michizane, an influential scholar and statesman of the Heian period. After his death in exile, he became revered as a kami to prevent him from imposing his wrath beyond the grave. Over time this reverence shifted, and he became to be regarded as patron of scholarship. These days it's very common for students to make offerings and pray to him in pursuit of academic success. In Touhou, Kanako-sama's ambition of becoming a kami of technological progress is perhaps an intentional, self-directed form of this process.

It should be noted that the Touhou canon contains references to some of these anthropomorphized Shinto kami in an unfictionalized way. In particular Silent Sinner in Blue contains numerous references to these kami. These include relatively obscure ones such as Ooguninushi no Mikoto and Izunome, but also very well known ones such as Ame no Uzume no Mikoto and even Amaterasu Oomikami herself. The kami and other ideas to Shinto feature very prominently in Silent Sinner, and there are also entirely unseen and more abstract or monstrous depictions of the kami within there too.

A selection of anthropomorphic kami from Silent Sinner in Blue whom Watatsuki no Yorihime (a kami herself) calls to aid her.

Form left to right: Izunome, Ame no Uzume no Mikoto and Amaterasu Oomikami.

The origin stories

While Shinto does not have quite anything like the Bible, Quran or the various Buddhist canonical sutras, it has origin stories that can be read as symbolical, allegorical elements and guidance for life in pre-modern agricultural society. Over time, new meanings have been found in these myths. These stories are compiled in two central texts: the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki. These two mythologies are partially overlapping, partially divergent, and with a different focus, intended for different audiences.

Nihon Shoki focuses more on the imperial lineage and the emperors and was modeled after Chinese court histories. It was written in Chinese and aimed at establishing Japan as a political entity recognized by audiences capable of reading Chinese – that is, basicaly everyone who was an educated East Asian at the time of it’s compilation in the 8th century.

Kojiki focuses more on the ancient mythological times and the creation myth. It was written in an early attempt at creating a written Japanese language. In fact, it used three separate attempts at such a system, creating a text almost incomprehensible by later generations. Compiled by the court historian-storyteller Hieda no Are, Kojiki was squarely aimed at the Japanese itself, offering the nation an origin story of it’s own, likely influenced but also set against Chinese influences. Many have found influence of Daoist thought in Kojiki.

While I will not go over the entire Japanese creation myth, I will offer a condensed version that should give the reader an idea of its contents. From only vaguely described origins of self-generated precursor kami arrive the first man and woman, Izanagi and Izanami. They create children who represent different islands – often thought to be specificaly Japan, sometimes Earth – and children who are primordial kami of various natural forces.

While giving birth to the kami of fire, Izami is horribly burned and dies. From her corpse emerge kami representing what have been interpreted both as necessities of early civilization, but also the wu xing five phase cycle of Taoism. These are the kami of soil, kami of water, kami of wood, and kami of metal, the kami of fire completing the cycle. Haniyasushin Keiki of Touhou is a fictionalization of the soil kami, and her depiction likely contains references to her siblings.

Enraged Izanagi slays the fire kami, which creates eight volcanoes and several new kami. Grieving, he wants to see his wife again, and travels to the underworld of yomi no kuni. There he finds her, but she is terribly disfigured and eaten by maggots. Enraged by Izanagi’s reaction, Izanami swears that every day she would take take every day the lives of Izanami’s descendants, but in turn, Izanagi declares that every day there would be more life born than taken.

Izanagi is driven out of the underworld by spirits dispatched by Izanami. After emerging from the underworld, Izanagi performs the first misogi, purification ritual, to remove the kegare, impurity or perturbance, he acquired from visiting the yomi. From this act of purification more kami are born, including sea kami and the three central figures of the next phase of the myth: the sun kami Amaterasu Oomikami, the moon kami Tsukuyomi no Mikoto and the kami of storms and seas Susanoo no Mikoto.

Amaterasu Oomikami and Tsukuyomi no Mikoto are happy with the celestial domains granted to them, but Susanoo no Mikoto is upset with the domain given to him. He storms the heavenly plane where Amaterasu Oomikami resides, and challenges her. They compete by creating children, and Amaterasu Oomikami’s children turn out to be stronger. Not accepting his defeat, Susanoo no Mikoto goes on a rampage and commits various tsumi, acts that create kegare. He ends up causing the death of one of Amaterasu Oomikami’s servants.

The death of her servant disturbs Amaterasu Oomikami so much that she decides to hide in a cave. This plunges the world into darkness and lets evil spirits roam free. The kami gathered together to deliberate a course of action. The wisdom kami Yagokoro Omoikane no Mikoto (lending surname to Yagokoro Eirin of Touhou) comes up with a plan. Amaterasu Oomikami is lured out of the caved by racket caused by the wild dance of the dawn kami Ame no Uzume no Mikoto. As she steps out of the cave, she is dazzled by her sight in a mirror. The kami of strength Ame no Tachikarao throws the stone sealing the cave and leads Amaterasu Oomikami out. In Touhou, this myth is referenced to in Silent Sinner in Blue, where calling forth Ame no Uzume no Mikoto is necessary for the process of calling out Amaterasu Oomikami.

From here on out the myths start moving towards the redemption of Susanoo no Mikoto through slaying of the monstrous serpent Yamata no Orochi, the birth of the more direct ancestors of the Yamato imperial lineage, and the conquest of the kunitsukami by the amatsukami. As the early part of the origin myth wraps up, the world has been created, life, death and nature have emerged, the conditions for civilization have been set up, social norms and definitions of aproriate and inaproriate behavior have been established, and the ways to interact with the kami have been described.

The very beginning of the origin story describes the emergence of various primordial forces. Here it is of interest how Izanagi and Izanami fail their two first attempts at making children, and how the emergence of civilization-enabling forces that allow for metalworking and agriculture are born out of destruction. It’s also possible to read these sections of the story as a kind of emergence or emanation of natural forces by division and refinement of an original undivided source, likely influenced by Taoism or sharing older Ancient North Eurasian influence with Taoism.

An important part of Shinto worldview, the idea that in the end life triumphs over death comes from Izanagi’s promise to overcome Izanami’s curse. This idea of life triumphing over death leads Shinto to place a great important on renewal and facilitating this renewal. Likewise, Izanagi’s first misogi forms the basis for a very core Shinto idea, that of purification and return to an unperturbed state, which I will go over in greater detail later.

The details of how the kami lured Amaterasu Oomikami out of hiding served as a kind of blueprint for how the early shamanic miko would summon the kami with their wild dances. While the kagura of the miko are no longer wild nor shamanistic, much of the various objects described in the story are still used in Shinto religious context. For example, the idea that mirrors are kami-reflecting objects comes from this particular myth.

Kegare, harae and misogi – cleaning of the kokoro

Let’s now move to Shinto concepts revolving around impurity and purification, or disturbance and return to normal. What Izanagi acquired in the underworld in yomi and his descendants have ever since accumulated is called kegare, a kind of both literal and metaphysical dirtiness. Accumulation of kegare is thought to lead to all kinds of negative things such as diseases, disharmony and bad luck. What exactly kegare is and consists of is difficult to pin down, as it includes both very literal dirt and more metaphysical ”contagion” that is caused by things like misfortune, childbirth, death and exposure to unclean things. To make things even more vague, not only people but also places can acquire kegare.

You can accumulate kegare by your own actions, but also by accident. These actions can include essentially harmless things or even positive things (such as getting dirty from work), but also a particular type of kegare called tsumikegare which is accumulated from doing tsumi, a kind of ”sin” or breach against norms. The literal idea of tsumi includes things like damaging rice fields, certain types of incest, zoophilia and ”skinning an animal backwards” but also things like getting struck by lightning, having tumors and being bitten by snakes. Tsumi leaves an impression that it's mostly things that would have been disruptive to an agricultural society. There are also elements of fear of sorcery and things believed to be infectious such as disease and bad luck in there too.

Over time interpretations around kegare have shifted, and there exists a diversity of opinion regarding what exactly it is. Some interpretations are closer to ideas of ”metaphysical impurity”, some see it perhaps in a way as some people speak of ”negative energies”, while some see kegare as something that cuts off people from their original state of being and connection to the surrounding world. Perhaps one way to see it is a kind of wear and tear of life that leaves one exhausted, disturbed, cynical and struggling to connect with the world if a critical mass of it is acquired.

As kegare is basically unavoidable, it's therefore very fortunate that kegare can be, and is, routinely purified through acts known as harae and misogi. Harae is the broader category of purification rituals, and it can include forms such was the ritual washing of hands and mouth when entering shrines, or purification done by Shinto priests. Often salt, water or the gohei rods (as wielded by Reimu, and the unusual variant Sanae uses) are used in harae. Some even speak of the kami itself doing harae with divine lght. Misogi is purification by full body immersion in water. This can be done in waterfalls, rivers or the sea. Often a place where a river and the sea meet is considered the best.

The ultimate aim of the purification is return to a state known as makoto no koro, or magokoro. This is related to the Japanese idea of kokoro, which literally translates to ”heart”, but in practice means something like ”heart and mind”. There isn’t a convenient single Western analogous term, as Western history has tended to separate mind and heart, body and soul. Kokoro is not only embodied within humans, but also within the world itself. Kokoro can be seen as something that exists akin to a field between a person and the world, the human and the world being in some way distinguishable only as the poles between which the kokoro resonates.

Makoto means ”true”, ”genuine” or ”sincere” and thus a state of magokoro is of ”true heart”. To be in such a state is to be truly receptive to the kami-filled world. A metaphor of a mirror is often used for describing the kokoro. When the kokoro become makoto, the human will realize they too are part of kami, they will reflect kami, not just reflect on kami. Conversely, a state of disconnection or distortion from the kami-filled world, a state of kegare, is often described as being like a mirror covered in dust that does not reflect the world properly. To sum it up, the aim of the various purification practices is to return the individual human to state that is receptive to the world.

These ideas of kegare and harae are also found in Touhou. In particular, the Lunarians are obsessed with purity and kegare causes them to weaken and age. It was the fact that Earth was so full of kegare that caused them to leave for the Moon in the first place. In Touhou, kegare is described as something that is born from predation, conflict and violence. This also includes entirely natural things such as animals hunting other animals for sustenance. This makes life itself a source of kegare.

One can also find references to Shinto purification rituals in Mountain of Faith. Yasaka Kanako-sama's large shimenawa hoop is likely partly a reference to the large chinowa reed loops used during the oharae, ”great purification” ritual. It's a very important ritual held twice a year, generally during summer and winter. Part of this ritual involves the shrine visitors being given paper dolls known as hitogata. It's thought that the hitogata will take the person's kegare. If there is a body of water nearby, the hitogata are deposited there at the end. This ties this ritual to the character of Hina Kagiyama. She is described as a nagashi-bina, a type of doll associated with another matsuri known as hinamatsuri, but there are similarities between the two festivals. She is also described as creating paper dolls in Symposium of Post-Mysticism, a likely reference to hitogata.

It should be noted that historically the idea of kegare and tsumi were much more stricter and literal, and certain groups of people such as the burakumin were considered irreversibly ”impure” because of their constant exposure to things that were considering kegare.

Prayers, offerings and matsuri

The various forms of purification are not done only for the well-being of the individual, but also as form of ritual purity that allows one to approach the kami in an unburdened, undistorted state and make offerings and pray. Offerings depend on the situation and purpose, but include money or food items, most commonly rice, water, salt and sake.

Likely the single most common form of offerings made in Shinto are small monetary donations left to the donation boxes at Shinto shrines by visitors. Most commonly these are coins, often five yen coins as ”go-en” is a homophone for ”honorable”. As the laws for religious freedom in Japan stipulate that government shall not support religious organization, the various shrines depend on these donations. Hakurei Shrine’s permanent state of poverty reflects a real plight faced by many smaller shrines in Japan.

After the offering has been made, the kami can be prayed to. Prayers are an expression of gratidute, and can be – and often are – used to ask for some kind of favor. These favors are of worldly nature, health, prosperity for family, success at education or work and finding love. The more worldly nature of these requests is related to how the kami are thought to deal with matters related to human affairs, but also as a way to make a distinction from Buddhism.

A perhaps unexpected type of offering the kami are said to enjoy is the company and joy of humans. This is why the various matsuri festivals form an important part of Shinto. While many Japanese regard these largely as irreligious communal festivities, there is still a core of a ritual at them. The participants of a matsuri at a shrine receive harae and prayers are read to the kami. Often offerings of sake to the kami are also shared with the participants of the matsuri. There's a small number of common Shinto matsuri including saitansai, setsubun and oharae. There are also an innumerable amount of local matsuri held by the various shrines. These local matsuri are known as reitaisai. Coincidentaly or not, there is a also popular annual Touhou fan event in Japan called Reitaisai, named so by ZUN himself.

The many forms of Shinto and the tension between imperial and local mythology & faith

Despite the founding myths centering around the origin of the imperial lineage, as evolution of an ancient and essentially animistic belief system, there are a great many local variations of Shinto. In fact, part of the controversy around the term Shinto comes from whether it is justified to roll all these divergent forms of spirituality and tradition under a single term. As a kind of compromise, it has been presented that there are multiple layers or manifestations of Shinto. These include forms of Shinto centered around the imperial family and the major deities, forms of Shinto centered around worship in the shrines, forms of Shinto practiced outside of the shrines as folk religion. It's very much possible for a person to engage in all of these. There are also a number of discrete sects of Shinto. Some purport to be purist, traditionalist forms that go back to Shinto without external influences, others incorporate practices found in other traditions such as breathing exercises.

This split into layers is in a way also reflected in Shinto beliefs and mythology, through the way the kami are divided into the heavenly amatsukami, the earthly kunitsukami and the myriad kami of yaoyorozu no kami. This hierarchy is seen fairly commonly to reflect a division between the ancestors of the Yamato imperial lineage, ancestors of those the Yamato conquered and kind of omnipresent life force or spirits of nature. The amatsukami would be the ancestors of Yamato, the kunitsukami those who were conquered and the yayorozo no kami are the everpresent nature spirits.

In Touhou, the amatsukami live on the Moon and are represented as being aloof, manipulative and occasionally cruel. The anthropomorphic kami found dwelling in Gensokyo would in turn be kunitsukami or yaoyorozu no kami – or amatsukami who abandoned life on the Moon, as in case of Yagokoro Eirin. This division between distant amatsukami and more involved kunitsukami can be seen to reflect certain tension between the imperial lineage centric aspects of Shinto, and the more folk religion centric aspects of Shinto. The attempts by Lunarians to use Gensokyo for their own ends can be seen as a re-telling of the tale of imperial and peripheral conflict.

Many of the kami who are featured prominently in Touhou are somewhat obscure, marginal or local in the real life. For example, the deity Haniyasuhime on which Haniyasushin Keiki is based on has no major shrines of her own. Even the fairly prominent Suwa sect is obscure enough that in one interview ZUN recalled how surprised he was to learn that almost nobody outside of Nagano knew of the deities of Suwa, which were very important to the culture of his childhood surroundings.

A smaller microcosm of this conflict found within Touhou is in Mountain of Faith, where Yasaka Kanako represents the imperial mythology, and Suwako Moriya the local native faith. The extremely rich Suwa lore deserves it’s own write-up, but one of the founding legends of the Suwa sect involves the conquest of Suwa by Takeminataka no Mikoto and the submission of a local malevolent deity known as Moriya. Takeminataka no Mikoto is a figure connected to the amatsukami and the imperia lineage, while Moriya is a wholly local figure. The reality of this situation is – as perhaps expected – more complicated, but this is how the narrative is portrayed, and how Touhou reflects it.

Sacred objects and locations

Shinto is very tied to very real, concrete locations in Japan where the kami are thought to reside, or descent to and be enshrined in. In fact, often the people do not so much revere a kami than rather all the kami in a shrine. While Shinto is practiced in many forms, it's widely thought that a person should revere the kami of at least two shrines: the shrine nearest to them and the Jingu. The nearest shrine (ujigami jinja) is thought to contain the kami that are most directly involved with protecting the individual and the Jingu enshrines Amaterasu Omikami who is thought to protect all Japanese. One can, and often does, revere kami from more than those two shrines. This can be done at the shrines itself, or then one can get ofuda (charms that in some way contain the kami) from the shrines and place them at the kamidana (home altar, ”kami shelf”) at their home.

A very important and particular category of sacred objects – and locations – in Shinto are the go-shintai. These are physical objects which are thought to be able to temporarily house the kami. These objects can be artificial such as gohei wands or shinzo sculptures of kami, but also natural objects such as trees, rocks, waterfall and mountains. Mountains are an especially important category of natural go-shintai in Japan. For example, Mt. Fuji is considered a sacred mountain.

Touhou project contains multiple references to go-shintai, both natural and crafted. The mountain that is the object of worship at Suwa Grand Shrine inspired the location of Touhou’s Moriya Shrine and gave the name to Mountain of Faith as a game. Reimu and Sanae both of course use gohei wands. The idea of go-shintai also most likely influenced the belief in tsukumogami, the idea that beloved items can develop a soul of their own. The Tsukumo sisters and Raiko Horikawa from Double Dealing Character are a reference to this belief. Go-shintai are also very straightforwardly referenced to in Wily Beast and the Weakest Creature, where Keiki-sama is described as creating items that can hold souls. She also offers to create a go-shintai of Reimu, apparently seeing Reimu as being a kami herself.

A common type of sacred objects in Shinto are various talismans, ofuda. A common type of ofuda are ones given to people to place in their home shrines, kamidana. These ofuda are thought to in some way contain the enshrined kami, allowing people to revere them outside of the shrine. In Touhou, Reimu uses various talismans, and the card-shaped projectiles are supposed to be talismans. This particular use might be more inspired by the fulu talismans of Taoism though.

Another very common type of go-shintai are objects modeled after the three treasures of the Japanese imperial family, the sword, the mirror and the magatama jewel. All of these three are commonly found in shrines, and small mirrors and magatama jewels are often also used at kamidana at home. These items are tied to the legend of Amaterasu Oomikami hiding in a cave and plunging the world into a darkness. The mirror and magatama were used in luring her out, and the sword was given to her by Susanoo-no-Mikoto as a reconciliatory gift. In Touhou, several of Keine Kamishirasawa's spellcards refer to these imperial treasures. The magatama are also featured prominently on Keiki-sama and Misumaru-sama.

An unusual feature of Shinto is that sometimes what exactly is enshrined at a shrine is completely unknown! Several factors contribute to this. The first is that what became Shinto is simply extremely ancient, and at times records have simply become lost over time. The second is that if the go-shintai is a small physical object, it is wrapped under increasingly layers of fabric and stored in increasing layers of boxes. Over time it's original nature simply becomes forgotten. The third factor is the Shinto tendency to place more focus on the shrines itself, as they can house multiple kami. In Touhou, this is reflected by the Hakurei god being essentially unknown.

It should also be noted that while Shinto is intimately tied with it’s sacred locations, it’s thought that kami can come and go from these locations, often seen as manifesting winds clattering the ema prayer boards at shrines. Some even think that kami essentially transcend human notions of time and space alltogether. The shrines are thus perhaps less containers and more simply the most favored places to be in.

Liminality and Holographic Animism

As Shinto very prominently features concrete sacred locations, be they a humble household kamidana or a large grand shrine, they are separeted from the profane world. Various ways exist to delineate sacred territory and objects in Shinto.

An extremely common and iconic way for marking sacred territory are the torii gates. Large gates mark shrine entraces, while smaller ones are used to make spaces sacred. These gates are treated with great reverence, and there are established customs regarding entering and exiting through them. Another way of marking sacred territory is the shimenawa rope, which is tied around or on certain sacred locations or objects. Commonly trees or rocks acting as yorishiro, places where kami can reside, are marked with shimenawa.

Because in Shinto worldview, the spirit world and material world are not separate but intermingled, this focus on delineating sacred territories creates a kind of focus on liminality. This is also reflected more broadly in Japanese culture. For example, the twilight hours are considered the time when people are most likely to encounter spirits. This interest in liminality is also rather strongly present in Touhou, and in multiple ways. An example of this the Great Hakurei Barrier separating Gensokyo from the outside world that divides common sense from the magical realm of Gensokyo.

The philosopher Thomas P. Kasulis who studied Shinto worldview made the case that Shinto worldview is essentially holographic, and that entering into sacred territory is entering into a kind of ”holographic entry point”. ”Holographic entry point” sounds like a term out of science fiction, but it actually comes from systems theory. There is a subset of complex internally related systems that are known as holographic systems. Within these systems, not only are the internal parts intimately linked, each part in some way or other reflects the whole. An example of this could be a hair from the body of a human. At first sight it seems like it hardly reflects the whole human being, but it’s possible to sequence a person’s DNA from a single hair. Therefore, a hair can be a holographic entry point to the biology of a particular human.

What does this have to do with Shinto? Kasulis presents that the Shinto worldview is essentially holographic. Since in the Shinto view we live in a tama-filled, kami-saturated world, all of existence then reflects the kind of wondrous qualities presented by the kami. Since all of reality is filled with kami, it is possible to perceive the kami-filled world in it’s wondrous totality everywhere. However, there are places, objects, even people who can act as kind of ”vantage points” or perhaps boundaries to be crossed, which will allow one to perceive the wondrous spiritual qualities of the kami-filled world with greater ease.

Shimenawa and torii gates are therefore examples of these holographic entry points. While shimenawa designates an object as being inhabited by kami, it also serves the function to call visible attention to the particular object in question. Torii gates serve as liminal spaces, and crossing one will ideally allow one to enter a place – or a state – where it is possible to perceive the kami-filled wondrous world in it’s totality.

Living kami and shamanic maidens

The ultimate expression of the idea of humans being part of the kami-filled reality is the idea of a human as a kami. While this idea is still present in some ways – such as sumo wrestlers being seen as kind of kami during the matches – it used to be historicaly much more porminent. The most famous example of these living deities were historically the emperors of Japan. After World War II Showa Tenno (Emperor Hirohito) declared that he is not an arahitogami, or a "presently manifest human kami".

In Touhou, Keine's spellcards that refer to events related to the imperial family might reflect this aspect of them "passing into fantasy". The imperial family and it's lineage still maintains an important role in Shinto by participating in certain rituals.

The imperial family however isn't the only family in Japan thought to have a divine lineage - and ultimately all humans are seen to be children of the kami. Of particular relevance to Touhou though is the fact that one family that is thought to have divine lineage include the priests of Suwa Grand Shrine. This is reflected in how Kochiya Sanae is not only a shrine maiden, but also a nascent kami in her own right. While the priests of Suwa Grand Shrine may not be seen as human kami anymore, many shrines are maintained by inherited lineages as a family affair. In Touhou, it’s at least implied that the position of the Hakurei Shrine Maiden is an inherited one.

Shamanism used to play a very prominent part in Japanese religion, and a trace of shamanism persists in Shinto up to this day. The kagura dances that are performed for the kami are a remnant of this. The miko originally filled a shamanic role, going into trance states through intense dancing. One of Reimu's spellcards in UFO is a reference to this, as are the dances she is forced to perform for the Lunarians at the end of Cage in Lunatic Runagate. Some more explicitly shamanic practices persist at the fringes of Japanese society to this day.

Eternal return and co-creation of the world

Shinto ideas about the spirtuality immersed in materiality, relationality, life overcoming death, renewal, purification and return to receptive state come to form a kind of core which could be said to be focused on the eternal co-creation of the world between humanity and the kami.

Because humans, the world and language are all part of the kami-filled reality and have kokoro, it’s possible to to use language to create connections between various parts of reality. Acts of creation are seen as acts of co-creation. If one were to write a poem about a landscape with genuine responsiveness, it would be the interactions between the kokoro of the poet, the landscape and the words that would create it. It’s no coincidence that Shinto prayers, norito, are essentially ancient poetry dedicated to the kami.

The deep relationality found in Shinto worldview gives rise to a final core concept. This is the musubi. Musubi can mean union, connection, tie, knot or even a rice ball in mundane sense. However, in Shinto, musubi is seen to be a creative power that exists in a vertical and horizontal way.

Vertical musubi is essentially a connection to the source of all creation. This source has been interpreted in various ways. Sometimes it’s seen to be the primordial kami that came before Izanami and Izanagi, and some forms of Shinto theology see all kami as ultimately being expressions or parts of a single kami that is the universe itself. This vertical musubi is thought to bring humans in relation with the kami. It’s said that it’s the kokoro allows humans to perceive or feel the vertical musubi.

Horizontal musubi are connections between things in the world of materiality, humans included. These connections that facilitate the act of life and creation are not less important than the vertical connection to the kami, and the world cannot exist without both. Sometimes the relationship between these two musubi has been compared to a tapestry, where vertical musubi gives the constant and continuing frame, and horizontal musubi gives the design that reflects the era and circumstances of it’s creation.

There are certain Shinto rituals which fullfill the role of eternal return, a concept coined by the anthropologists Mircea Eliade. While Eliade has been criticized for overapplying the concept, it is exceptionally fitting in the case of Shinto. In this context, eternal return refers to the belief that through ritual practices it’s possible to return to the mythical age. An example of this in Shinto would be sumo wrestling as a return to a battle between Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata to decide the ownership of Japan. One of the key figures in the development of Shinto, Motoori Norinaga, who deciphered the ancient written Japanese of Kojiki, saw himself as taking part in the creation of the world through his work.

As Touhou works with ancient mythology related to Shinto, one can see it as being part of this process of eternal return and weaving of musubi. Here Touhou would fullfill the role of horizontal musubi, giving designs and interpretations that reflect the era and circumstances of it’s creation.

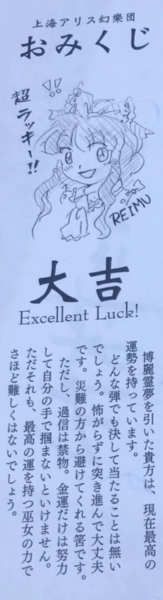

Omikuji

The last bit of Shinto related practice worth mentioning in relation to Touhou is the omikuji. Omikuji or O-mikuji (”sacred lot”) is a form of fortune-telling practiced by Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan. They are usually received by making a small offering and randomly choosing a paper strip from a box. They are one of the traditional activities of a shrine or temple visit.

The omikuji are commonly classified by how good or bad fortune they promise for the one who has drawn them. Generaly they are ranked from Misfortune to Great Blessing in a seven step scale. In addition to the general outlook, omikuji offer more specific fortunes for various fields of life. These can include things like travel, business, romance, studies, disputes, health and so on.

There is a canonical, fully functional Touhou fortune telling book based on the omikuji system called the Whispered Oracle of Hakurei Shrine. Before the release of the book, ZUN had sporadicaly produced and distributed Touhou-themed omikuji. The omikuji are of importance in Touhou canon too, as the Whispered Oracle ritual that Reimu performs is used to re-define and re-stabilize Gensokyo. This is reminescent of the idea of using rituals to restore the functioning of society after a crisis.

One of the old omikuji produced by the Head Priest of Hakurei Shrine himself.

You may draw your own omikuji online here!

Local or universal?

Since Shinto is extremely tied to Japan, physical locations there and it's culture, many see Shinto as an indigenous, if not an ethnic Japanese religion that can not effectively or meaningfully be practiced outside of Japan - or by non-Japanese. The shrines in Japan do welcome all people who perform the harae and behave themselves, so it's not exclusionary in that sense. The fact remains that practicing Shinto as an outsider, especially outside of Japan is difficult. For example, a proper home shrine is thought to require ofuda from an ordained Shinto priest. For those interested in practicing Shinto outside of Japan, performing yohai is probably the best option.

When it comes to shrines in Japan, I personally found them very welcoming, even beyond the usual Japanese hospitality. Acting respectfully, ttudying local social norms and dressing in an aproriate manner is however important. I'm not the only one who found shrines welcoming or experienced a kind of sensation of "returning home", as Kasulis' Shinto: The Way home was inspired by non-Japanese's peoples experiences of these feelings. So if you are interested in Shinto and plan to visit Japan, I strongly encourage you to visit the shrines.

There however do exist certain Shinto sects (which some might consider separate religions) that have a more international presence, and for example the network of Inari Ookami worshippers facilitate access to proper kamidana and ofuda even for people outside of Japan. There are also a small handful of Shinto shrines outside of Japan. So perhaps rather than being entirely "ethnic" religion, Shinto requires one to join the community of followers, perhaps as one would expect from such a community-oriented religion. This contrasts with certain "new religions" in the West, which many think of being very individualistic and self-identity based.

However, there have been certain modern movements, minority as they may be, making the argument that there are universal elements within Shinto that transcend the boundaries of nations and even religions. It has been argued that a certain kind of "natural religion", a spontaneous awareness of divine that can be found by observing nature and it's patterns, is at the core of Shinto. This can certainly be cultivated in any place, in any culture. While Shinto is often said to be sparse on ethics, it does encourage sincerity, honesty, dedicated work and gratefulness towards not only other people, but everything that makes human life possible. These too are values that can be cultivated by everybody regardless of place or culture.

Conclusion

Shinto is not an easy topic to write about. The very term Shinto itself might be contested, it’s origins might be murky and it is so entangled with Japanese culture that it’s hard to say where ”Shinto” starts and the ”local worldview” ends. In some way the struggle of these definitions might as well be reflective of greater reality, where all definitions are more or less contested, murky and bleed into other categories… However, whether ”Shinto” constitutes a religion or a political project or an umbrella term for traditions, it can be an useful analytic category, or at least as a starting point.

What the things that were Shinto a thousand years ago are obviously not entirely the same that are Shinto today, and studying Shinto and it’s development can reveal much about Japanese history and culture. Different elements move to the center or recede to the margins and time marches on and culture changes. However, there might very well be an ancient core that captures something truly eternal, something that can be very illuminating when it comes to the nature of reality itself. And no matter the origins, history or present day, if one aproaches the shrines with a heart and mind that can be quiet and present, filled with respect and curiosity, perhaps the kami will show themselves. Human terms and ideas can change, but they might just have always been there under various forms.

There is a kind of further liminality and internal tension within Shinto. It’s of between hidden and visible, of secret and known, of welcoming and obscure. Hidden and unknown kami, a rich mengarie of unseen spirits, the way of seeing the world itself as being alive, and the focus on location, lineage and ritual give Shinto a kind of secretive, esoteric air about it for the outsiders. At the same time, anyone who partakes in the purification rites, gives an offering and behaves is welcome to visit a Shinto shrine and take part in it. From the Western perspective it's a truly unusual mix of the hidden and welcoming, perhaps much like Touhou itself is.

Perhaps it’s even possible for one to experience that sensation of ”returning home” that inspired Kasulis to take a deep dive into Shinto in an attempt to explain it. Japan has this reputation of being a kind of insular society, and there is an element of truth to it. However, to some extent this is a kind of modern myth, colored by the sakoku period, an act of self-defence against attempts of christianization and colonization by European powers. Before that, Japan had for thousands of years integrated Ancient North Eurasian, Polynesian, Chinese and Korean influences and population that sometimes meshed, sometimes clashed, but ultimately always settled into a new equilibrium and became an organic, shared culture deeply shaped by the land of the islands themselves – and if you believe in such things, the kami there. If Korean merchants and Chinese Buddhist monks could feel and come to revere the kami, perhaps there is nothing but a barrier of ”common sense”, encultured expectations, stopping a modern Western person from feeling the kami of the islands and mountains. And perhaps the islands and mountains themselves are simply a microcosm, a holograph, that reflects a much larger shared reality saturated by what Shinto calls kami.