Buddhism

Part of the Koyasan temple complex, the spiritual and physical center of Shingon Buddhism which greatly influenced Japanese culture

Buddhism is the second large religion present in Japan, and arguably the one which is unambiguously a religion by any definition. While Shinto is a modern incarnation of indigenous beliefs, Buddhism is a world religion that originated from areas of present day India and Nepal. As it happened in many places where Buddhism became introduced to, it assimilated local practices and in turn influenced how locals viewed their own traditions. Over time Buddhism and Shinto have over time become to complement each other. In the popular practice, Shinto is concerned about this life, and Buddhism about the ultimate fate of the individual. In practice many Japanese ”live Shinto and die Buddhist”, and Buddhist institutions handle most of funerals.

The two religions have not always had such a coexistence, and have at times been violently at odds with each other. The history of Japan has seen everything from near total Buddhist domination to warlords turning against powerful Buddhist organizations to persecution of Buddhism at the start of Meiji Restoration.

In modern Japan, Buddhism has become a kind of funerary religion and bullwark of cultural heritage. That isn’t to say that there are not practitioners or lay believers who are interested in the core of Buddhism, which deals with the ultimate nature of reality, human perception, ethics, the afterlife and ultimately liberation from samsara, the cycle of birth, struggling, craving and death.

Buddhism rather diverse, and there are three main larger branches of Buddhism, Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana. All three however share the same origin and certain core ideas, so they shall serve as a natural starting point.

The birth and core ideas of Buddhism

Buddhism was founded by Siddharta Gautama, often simply called the Buddha. He is thought to have lived around the 5th century BCE in present day India and Nepal. According to Buddhists, he was born a prince who was raised in a very sheltered environment. When he discovered how life outside of the palace had things like old age, disease and death, he became shaken and started to wonder if there was more to life. He renounced his nobility and became an ascetic hermit. The severe asceticism failed to bring him the enlightenment he sought and he renounced it too. He started to seek a path of moderation, realized that the eightfold path is the key to liberation and achieved enlightenment or awakening while meditating under a tree.

From this experience the central ideas of Buddhism started to formulate. They can be represented as follows: All things are reborn into different forms in an endless cycle. Life is filled with ”suffering” or ”unsatisfactoriness” (dukkha), a constant cycle of craving and disappointment. It's however possible to become enlightened and become awake to the true nature of reality, which leads to nirvana, the extinguishing of dukkha and the termination of the cycle of death and rebirth. This termination of the cycle is mysterious, but not an annihilation, but rather a transcendence.

In the Buddhist view, the cosmos is divided into multiple layers or planes. There are differences between the various branches in how this is conceptualized, but common elements are that there are various lower realms of suffering, the human realm and a realm of devas, deities. Some branches also posit further layers inhabited by semi-enlightened and enlightened beings. The Buddhist worldview includes transmigration, not of the soul as the concept implies a permanent, unchanging essence, but a kind of ”mindstream” that is shaped by it’s conditions and willed actions – karma.

Based on one’s karma, conduct in life – generally understood to be through conditioning caused by actions and not as judgement by outside force – the various entities can move from one realm to another. The Buddhist cosmology tends downwards, and it’s exceedingly difficult to get out of the realms of suffering. As everything is impermanent, even the mighty devas, non-enlightened deities, living in luxury are subject to suffering, old age and death.

Buddhism is sometimes erroneously regarded as being ”atheistic”, because Buddhism lacks notions that are broadly comparabled with Western idea of ”God”, and some forms of Buddhism disemphasize reverence of deities, particularly the unenlightened devas. However, Buddhism does not deny the existence of the devas or other supra- or inframundane entities like ghosts, demons, nature spirits or the wrathful asuras who try to usurp the rule of the devas. Sometimes these entities are understood to be "mental constructs", but the Buddhist ideas surrounding what exactly the ”mental” is and the non-dual nature of reality make this much less straightfoward than one would assume. "It's all in your mind" in the common Western sense is not right, as "it", "all", "you" and "mind" are interpreted in a rather different manner from the current Western ideas. While some forms of Buddhism disemphasize devotional practices, other forms place emphasis on reverence towards enlightened beings, including otherworldly entities, that is similar to practices of many other polytheistic religions.

A core Buddhist idea is that of ”emptiness”, which often gets misrepresented in a nihilistic way. However, there are very major differences between the difference major branches as to how exactly this concept is interpreted. The differences between interpretation will be looked in detail further on, but broadly speaking emptiness in Buddhist context means that things are thought to lack an essential, unchanging instrinct nature of their own.

The Buddhist idea of emptiness is related to the core idea of dependent origination. This is a deeply relational form of ontology that could be contrasted with Western notions of causality where instead of isolated causes and outcomes, everything is conditioned by everything else. An example of this could be ”the carpenter made a chair”. This can be represented as a linear, simple causational process, but the view of dependent origination would be something like this: there is no chair without trees or a carpenter, no trees without soil, water and sunlight, no carpenter without his parents or his tools or the food he eats… Certain interpretations of the concept of emptiness would actually posit that the category of ”things” is a kind of illusion to begin with, as lacking instrinct nature, there is simply an undivided, profoundly interconnected reality that is simply cleaved into ”things” by human perceptions.

Buddhist ethics

Buddhism is very much occupied with ethics. Buddhism is notable for featuring quite many numbered concepts as mnemonic devices for remembering it's teachings. The central teachings of Buddhism are thus often presented in the formula of ”four noble truths, eightfold path”. The four noble truths are as follows:

1) Life is ”suffering” or ”dissatisfaction” (dukkha)

2) Suffering arises out of craving

3) Suffering can be stopped if craving is stopped

4) The way to extinguish craving (to reach nirvana) is to follow the eightfold path

This eightfold path then is as follows:

1) Right view (or wisdom)

2) Right intention (or motivation)

3) Right speech (in particular honesty and kindness)

4) Right conduct

5) Right means of livelihood (not harmful to others)

6) Right sustained effort (to avoid evil thoughts)

7) Right mindfulness

8) Right concentration (or meditation)

This practice of the eightfold path is thought to promote self-examination and a spiritual life. While the list is numbered, it's not really an ordered list. All the elements are thought to be interwoven, and the eighth fold, meditation, is thought to be crucial. It's thought that meditation sustains the other efforts and brings matter into proper perspective. Sometimes it has even been presented by Buddhists that sustained meditation alone can lead to the adoption of the Buddhist ethical system.

Buddhists tend to be divided into lay people and monastics (sangha). While the various ethical guidelines are much stricter for the monastics and historically lay people were not expected to meditate, both groups are expected to adopt a baseline of five precepts. These precepts are:

1) Do not kill

2) Do not steal

3) Do not commit adultery

4) Do not lie

5) Do not take intoxicants

There’s some variation on these precepts, particularly in Japan where many lay practitioners take a variant known as Ten Precepts, which notably does not forbid intoxication. Owing to a mix of doctrinal and historical reasons, the Japanese monastic wovs are not as restrictive as in other forms of Buddhism.

These precepts are complemented by four virtues to be cultivated: friendship, compassion, wishing happiness for others and equanimity.

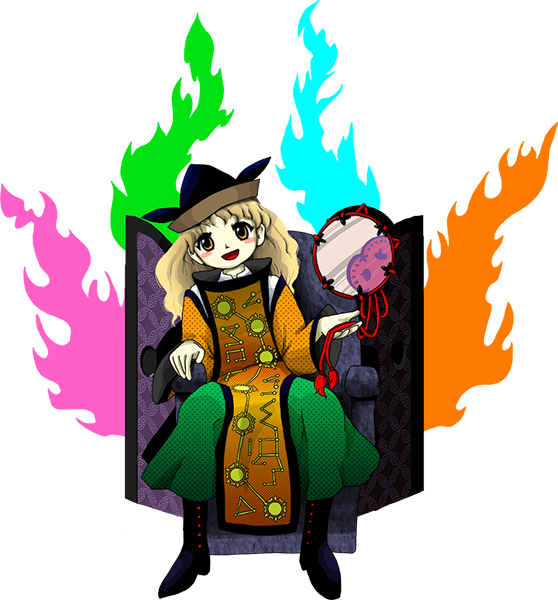

The idea of upholding the ”three treasures” tends to be a central part of identity for most Buddhist groups. While the phrase is familiar to anyone who has played Undefined Fantastical Object, the three treasures are:

1) The Buddha, as an ideal model for each follower

2) The Dharma (teaching, universal truth or law)

3) The Sangha (the religious order, but also more broadly the Buddhist community)

The two main branches: Theravada and Mahayana

As mentioned before, Buddhism is split into two major branches. They are the Theravada (”Council of Elders”) and Mahayana (”Great Vehicle”). While they share certain core ideas, including the ideas of samsara, nirvana, eightfold path and the broad outline of ethics they have rather large differences in views regarding some topics such as buddhahood, nature of reality and aproriate types of practice.

Theravada is a branch of Buddhism based around the Pali Canon, the most complete existing early Buddhist canon. Geographically speaking, Theravada is the dominant form of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Out of all the branches Theravada tends to be most conservative regarding doctrine and precepts. What essentially separates Theravada from other branches is that they reject the Mahayana and Vajrayana sutras, and do not recognize the canonicity of doctrines and practices in these sutras or the existence of many buddhas and boddhisattvas found in them. Viewing Theravada as the ”original” Buddhism however isn’t quite right, as there were forms of Buddhism and Buddhist texts predating Theravada, and the Pali Canon was written after Siddharta Gautama’s death. Current scholarly consensus is that Theravada and Mahayana ideas developed in parallel, not in sequel.

Theravada regards buddhas as beings who discovered the path out of samsara themselves and then taught it to others, and it rejects the idea of there being multiple presently-manifest buddhas and regards boddhisattvas as exceptionally rare beings who made a wov in front of a living buddha. Thus the highest presently-achievable ideal for theravada practitioners is the arahant, ”worthy ones” who have realized the way out of samsara by following the dharma as taught by the most recent buddha, Siddharta Gautama.

An important part of Theravada is the abhidharma, a highly systematic treatise on combinations of physical an mental processes known as dharmas that is found in the Pali Canon. It has been described as being simultaneously ”philosophy, psychology and ethics” and a ”framework of a program for liberation” from samsara. The goal of the abhidharma was to create a complete description of all the phenomena that make up the world.

There is a Buddhist concept called jhana which has become recently popularized. This refers to different states of meditative absorption. While the idea of meditative absorption is in some way present in all branches of Buddhism, it’s specificaly the Pali Canon concept that has become popularized. They are divided into jhanas with form and formless jhanas. The jhanas with form are states where the meditator progressively sheds various attachments, desires and ”unwholesome states” and enters a state of mental clarity and equanamity, while experiencing sukha, a pleasant bodily state. The formless jhanas are much more difficult to describe and include things like ”infinite space” and ”infinite consciousness”. There’s however some debate within modern Theravada over the importance and necessity of these states.

Third formless jhana is a "vast emptiness beyond space or consciousness".

Mahayana is the other major branch of Buddhism, and is the dominant form of Buddhism in East Asia. The major difference between Theravada and Mahayana is that while Mahayana accepts the early Buddhist core teachings, it also incorporates the Mahayana Sutras. These sutras have a more inclusive idea of bodhisattvahood, focus on achiving enlightenment for the benefit of all beings, and have divergent ideas compared to Theravada on fields such as the nature of buddhahood and ontology.

The origins of Mahayana Buddhism are unclear, but it developed in India. Earliest unquestionably Mahayana iconography is from 180 CE. It’s very likely that for a very long time Mahyana was a set of texts, practices and doctrines that existed within early Buddhist schools. Over time these developed into discrete schools of thought under the Mahayana umbrella. Mahayana is very internally diverse, and over time the differences between different sub-branches have become rather large. As Mahayana became disseminated throughout East Asia, it likely picked up influences from local cultures and religions which further shaped and diversified it.

The bodhisattva path is perhaps the defining difference between Theravada and Mahayana, and it’s from this idea that the ”great vehicle” of Mahayana gets it’s name. In Mahayana context, boddhisattvas are beings who seek attain awakening in order to help other beings reach awakening. While in theravada, the boddhisattvas require the presence of a living buddha, in Mahayana the genuine intention to develop boddhicitta, a mind directed at bringing enlightenment to all beings through wisdom and compassion, is the start of the boddhisattva path. There’s some differences in Mahayana as to how inclusive this path is, with some seeing it being open to everyone, and some to a very dedicated few.

The Mahayana Sutras feature a vast cosmologies and mythological histories, which include numerous different realms of existence, multiple celestial boddhisattvas and buddhas and new ideas regarding the nature of reality and buddhahood. Mahayana views buddhas and very accomplished boddhisattvas as having a kind of transcendental or supermundane character, existing outside of the cycle of death and rebirth, but still reaching out to assist and teach others.

The inclusion of various celestial – and in some cases even lower realm – buddhas and boddhisattvas and different realms associated with these beings has given rise to diverse and rich tradition of deity-related practices and ideas. For example, a popular subset of Mahyana Buddhism is Pure Land Buddhism, which focuses on salvation through faith in Amida Buddha and the practice of nembutsu, the chanting of Amida Buddha’s name. Amida Buddha is a boddhisattva who made the promise that any who with sincere faith and intent calls out to his names will be reincarnated into this Western Pure Land. Popular exoteric view holds this to be a kind of paradisical world or alternative dimension, while some esoteric interpretations see it both as a different place and something that is immanent in everyday reality. The concept of Pure Lands is refered to in Touhou, albeit with a meaning that is different from the Buddhist one.

Mahayana sutras themselves are also objects of reverence and veneration, and it’s believed that copying, reading, reciting and contemplating them will bring merit and protect practitioners from harm. This has led some to postulate that Mahayana started originally as a kind of sutra faith. Many of the Mahayana sutras contain elements urging reading, copying or reciting them, and such form an important part of Mahayana practice for many. Many of the sutras also contain dharanis, shorter incantations which are believed to bring beneftis when recited. For example, the ”gyate gyate” that Kyoko Kasoudani in Touhou chants is part of the Heart Sutra mantra, intended to awaken a kind of transcendental wisdom in the one who recites it. The whole Heart Sutra is an extremely popular subject of recitation and copying in Japan.

Please gyate gyate mindfully!

While Theravada viewed Siddharta Gautama as the most recent buddha and buddhahood as a kind of personal quality of awakening, Mahayana views buddhahood as a buddha-nature that is understood as a latent quality in all sentient beings, or as all beings being allready enlightened but this quality being hidden by afflictions. Afflictions here refer to mental states that cloud the mind and result in unwholesome actions. This buddha-nature is a kind of primordial, luminous mind or a potentiality for awakening that is the true nature of all things.

A good example of the Mahayana idea of buddha-nature comes from the Lotus Sutra, a foundational Mahayana sutra. In it, the historical Siddharta Gautama is revealed to be just a particular manifestation of an incomprehensibly ancient, transcendental buddha that achived awakening countless aeons ago and has ever since sought to awaken every being in countless realms. In more modern terms, one could call this idea of buddha an all-encompassing mind, perhaps even a kind of cosmic mind. This is a radicaly different idea from awakening as something that is achieved as a human, and buddhahood becomes a process of realizing one is part of this immense cosmic mind.

The Mahayana schools have a much broader range of interpretations for emptiness in the Buddhist sense. In Theravada, this is seen as emptiness of the five aggregates that make up the human experience. In Mahayana, emptiness is seen in broader terms. These include interpretations of emptiness as the impermanent, changing nature of all things and even concepts, the lack of duality between the perceiving subject and perceived object and the idea that everything but the buddha-nature is subject to emptiness.

This concept of emptiness in Mahayana sense is part of the idea of prajnaparamita, ”perfection of wisdom” or transcendental knowledge. This term comes from a corpus of sutras known as Prajnaparamita Sutras, which explore the things that make up this perfection of wisdom. They include topics such as things lacking an unchanging essence, the illusory nature of concepts humans place upon things, things being ”unborn” ie. an absence of origin, and the madhyamaka philosophy of Nagarjuna, a philosopher who was essential to the development of Mahayana. Nagarjuna’s thinking is a summation of emptiness and interdependent becoming: things lack an independent unchanging essence because they arise in infinite chains of co-dependence with everything else. ”Emptiness” too is empty, and does not exist somewhere elsewhere our outside of the world of phenomena, it is simply a categorization. Prajnaparamita Sutras link the development of this transcendental knowledge with the bodhisattva path, and later additions to the sutras make provisions for developments such as Pure Land practices.

There is a type of Buddhism known as Vajrayana, or Esoteric Buddhism, which is sometimes considered a subset of Mahayana, sometimes a branch of it’s own. ”Vajrayana” means ”vajra vehicle”, which is a reference to a mythological diamond-thunderbolt weapon, used as a metaphor for sudden and lasting enlightenment. Vajrayana shares the broad outlines with Mahayana, but they incorporate tantric practices and have a number of sutras unique to Vajrayana schools.

Tantra is a broad group of spiritual practices originating from the Indian subcontinent that have been adopted by multiple traditions, the name meaning ”expansion-device”, ”salvation-spreader” or simply ”weave”. The types of tantric techniques used in Vajrayana include mantras, dharanis, mudras, mandalas and visualization techniques. It should be noted that not all of these are exclusive to Vajrayana, but they are especially prominent in Vajrayana or used in different context there.

The context for these practices in Vajrayana is to hasten the process of awakening. However, at least historically, and still likely outside of Western context, these included more ”magical” practices intended for achieving particular outcomes through spiritual means. Vajrayana practitioners, which sometimes include people operating outside of monastic contexts, also engaged in practices such as healing, exorcising hostile spirits and protecting people from spiritual threats. These practices have had a tendency of leaking out of the official context and becoming part of folk spiritual practices. The mantras and mudras also influenced Japanese depictions of magic in fiction, sometimes in forms closer to reality, sometimes in more fantastic manifestations. If you have ever in Japanese fiction run into a character chanting while making hand gestures, you are witnessing echoes of Buddhist history.

Vajrayana is the dominant form of Buddhism in the Himalayas, but it’s also found in Japan as a minority branch. Tibetan Vajrayana has split into multiple schools, and Tibetan Vajrayanas has a number of sutras and teachings particular to these schools. These are outside the scope of this text. The Shingon school represents Vajrayana in Japan, and the Tendai school incorporates elements of Vajrayana. Japanese and Himalayan Vajrayana diverged from each other, and Japanese Vajrayana lacks the more transgressive and outwardly sexual elements present in the Himalayan Vajrayana.

Shingon and Tendai had tremendously large impact on Japanese culture, and were for centures the dominant forms of Japanese Buddhism. These days they are no longer so powerful, yet remain part of Japanese Buddhism. The various mudra hand gestures, chants and entities associated with Vajrayana saturate much of Japanese popular culture, including Touhou. This influence and specific things referenced will be explored later, but first an introduction to how Buddhism spread to Japan and how it influenced Japanese culture and society is required to set the context.

Buddhism in Japan

Buddhism spread to Japan via Korea and China. The introduction of Buddhism to Japan began in the 5th century, roughly a thousand years after the life of Siddharta Gautama. While the introduction of Buddhism was slow at first, it did eventually raise great interest. The arrival of Buddhism is generally dated to either 538 or 552, the arrival of a Buddhist mission sent by the Korean king Seong of Baekje. The support of the powerful Soga clan and Korean immigrant clans like the Hata helped the initial push for introduction of Buddhism. A prominent figure in the establishment of early Buddhism was Prince Shotoku (574-622), who in alliance with the Soga clan defeated the Nakatomi and Mononobe clans who opposed the introduction of Buddhism.

While Buddhism faced initial resistance, even a violent one, it eventually became the dominant religion, first of the court, and then spreading out to the commoners. However, Buddhisms’ approach to dealing with local pre-existing traditions has generally speaking been very different compared to Western monotheistic religions. It has generaly speaking tended to assimilate or syncretize with local beliefs, and the same happened in Japan.

Early on the local kami were seen as unenlightened beings that needed to be saved, and this included things like reading sutras to the kami. Eventually this changed into a process where the local deities became seen as fully enlightened or ”provisional” emanations of buddhas and boddhisattvas. This has sometimes been represented as linear process where the kami took on more and more enlightened qualities. In reality this process was much messier and occasionally featured ostensibly Buddhist entities escaping the confines of orthodoxy and developing popular faiths of their own. Sometimes the process was one of Buddhist deities becoming ”nativized” and adopted into local practices under names or roles divergent from their canonal roles.

Over time Buddhism would gain great influence and status, but would also start splintering into numerous smaller sects. Sometimes the sectarian process would be initiated by a monk visiting China to get the newest Buddhist scholarship, while sometimes it would begin from a desire to popularize Buddhism or to reform the practices. Sometimes it was even caused by strong outside intervention, such as secular military interventions against powerful sects that had their own armies of warrior-monks.

It’s this split into various sects and their competition and intermingling that is particularly notable in history of Japanese Buddhism. While sectarianism also happened in other Buddhist countries, the late and sequential adoption led to a rise of exeptional numbers of different sects whose influence and importance varied over time.

For around 200 years after the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, it was mostly limited to elite circles of the court and immigrant clans. The imperial system, especially the Soga clan, established and patronized temples, but also regulated Buddhist religious life. Rituals centered around various sutras and providing magical protection to the ruling class formed an important part of this prototypical Japanese Buddhism. Around the Hakuho era from 645-710, Buddhism slowly started to spread out of the Yamato province but also became more strongly centralized around imperial family.

The earliest traces of sectarian Japanese Buddhism started to rise during the Nara period from 710 to 793. Rather than being discrete religious sects, these are best understood as kind of ”study groups” who focused on different elements of or approaches to Mahayana Buddhism. Temples often had monks versed in several schools of thought. These early schools have today largely gone extinct or evolved into new forms of Buddhism. The new imperial capital of Nara saw the construction of many impressive Buddhist temples, some of them surviving to this day. The Nara period also saw the appearance of Buddhist preachers operating outside of the state-sanctioned system, who sometimes incorporated indigenous or Daoist practices. Some of these self-ordained monks were critical of the state Buddhist system, and were thus persecuted by the state.

The Heian period from 794 to 1185 saw the imperial capital being moved to Kyoto, and the emergence of the first Japanese sects of Buddhism. The monk Saicho (767-822) studied Tiantai Buddhism in China and brought it to Japan, establishing the Tendai school. Saicho made an extremely influential decision to use the boddhisattva vows instead of vinaya precepts for ordination. The vows place greater focus on the bodhisattva ideal as opposed to the strict monastic rules of the vinaya. Future sects would largely inherit the use of these wovs, and Japan has ever since seen repeated debate whether Japanese Buddhism should return to stricter precepts. As Tendai became the Buddhism of the Imperial family, it had an incredibly powerful position. Under the leadership of Kukai (774-835), the Shingon school of Vajrayana Buddhism was established. Shingon also became influential over time, supported by nobility. These two schools managed to develop with less direct state control, and would grow to become extremely influential and powerful over time. Changes in laws also saw requirements for Buddhists priests to specify which school they belonged to, sowing the seeds for sectarianism.

Later Heian era would see Buddhism spreading more widely among the population. The two forces contributed to this. The first one was the popularization of Lotus Sutra veneration, spread by hokke hijiri, ”Lotus Holy Ones”, Buddhist preachers who operated outside of formal structures. The other factor was the emergence of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism, which offered very accessible forms of practice to even commoners. Syncretism between Buddhism and native traditions emerged in forms of new spiritual groups like the shugenja mountain ascetics. Many shrines started incorporating Buddhist clergy. At this point Buddhists sometimes viewed the kami as earthly beings in need of salvation, and at other times manifestations of enlightened beings. The Heian period was also a culturally rich time, and Buddhism exerted strong influence on performing arts and poetry of the era.

As the influence and power of Shingon and Tendai grew, they started competing for influence both on worldly and spiritual domains. Both produced produced rituals and theological framings intended to shape the course of the nascent Japanese nation. However, often the various deities which Shingon and Tendai tried to fit into their reality-defining mandalas would escape their confines. This lead to the emergence of various popular faiths centered around certain deities, some of which were regarded as quite lowly and troublesome beings by earlier Buddhists. The growth in the power of Shingon and Tendai also included these two schools establishing armies of sohei warrior monks.

The Kamakura era of 1185 to 1333 saw the transfer of power from the imperial court to the shogunate. This era was marked by social instability and the attempted Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281. This mood of social crisis contributed to the emergence of new schools of Buddhism. The new forms of Buddhism were also motivated by perceived corruption, earthliness or philosophical shortcomings of the dominant schools of Buddhism, especially Tendai.

The new forms of Buddhism that emerged during this time include the transfer Chan Buddhism from China, becoming Zen in Japan. Eisai (1141) established the Rizai school of Zen and Dogen (1200-1253) the Soto school. New forms of Pure Land Buddhism emerged, such as Honen’s (1133-1212) Jodo shu and Shinran’s (1173-1263) Jodo shinshu. Both were heavily focused on chanting Amida Buddha’s name, and believed in the idea of mappo, or dharma decline, and that Japan was entering an age where other forms of Buddhist practices were becoming fruitless.

A wholly Japanese form of Buddhism emerged from Nichiren’s (1222-1282) teachings. He was driven by belief in dharma decline, and believed that the various disasters Japan was facing were caused by people practicing and corrupt form of Buddhism. He believed that veneration of the Lotus Sutra was the only form of Buddhist practice suitable for the age of dharma decline. He faced much resistance and was exiled twice, but he would leave a lasting legacy in the form of Nichiren Buddhism.

Interestingly enough, all the founding figures in these new schools were formed Tendai monks. In a sense, this process can also be seen as a shattering of Tendai’s attempt at grand synthesis of Mahayana and Vajrayana thought. Beyond the emergence of new schools of Buddhism, there were also people within Tendai and Shingon who attempted to return to a more disciplined, traditional, meditation focused Buddhism. Others within these sects started reaching out to and caring for marginalized, lower class groups of people and the ill.

The late medieval era in Japan from the start of the Muromachi period in 1336 to the start of the Onin war in 1467 saw the various new schools of Buddhism consolidating their power. Many of them remained somewhat marginal or strongly associated with more established forms of Buddhism, such as many Pure Land schools being seen as kind of offshoots of Tendai. The exception to this was Rinzai Zen, which managed to gain considerable influence during this time as the shogunates patronized it. Decentralization of power led to certain powerful temples developing great local influence, and at times wielding great armies. The Muromachi period was also an era of increased mobility, and despite the emerging sectarianism, some monks ended up studying in multiple lineages. Thought about the relation between buddhas and kami also evolved during this era, and the various manifestation theories were further developed during this time. These include the idea of gongen, or ”provisional” manifestations of buddhas and boddhisattvas as local kami.

The Onin war of 1467-1477 saw the start of the Sengoku era which lasted untill 1603. This was a state of prolonged civil wars in Japan, which saw the dissolution of central political power as competing daimyo warlords fought each other for power. During this time, many Buddhist temples and monasteries were destroyed. A notable incident is the destruction of Enryaku-ji by Oda Nobunaga in 1571 which ended Tendai dominance in Japanese Buddhism. This destruction cleared way for the ”new” Kamakura era forms of Buddhism to rise to greater prominence. The Zen, Pure Land and Nichiren schools developed more comprehensive doctrinal curriculum which allowed them to become more independent.

The increased need for funeral services also led to the dissemination of the newer forms of Buddhism, particularly Zen and Pure Land sects. This era saw the emergence of mortuary temples, which were intended to specificaly serve the needs of the dead. Another change temples faced was loss of court patronage. This led to new practices like offering viewings of relics and esoteric items in exchange of a fee for broader audience.

This era also saw the rise of militant Buddhist leagues, the Ikko-Ikki who were Pure Land leagues and the Nichirenist Hokke-Ikki. The dissemination of firearms enabled leagues formed by a core of merchant and farmer classes to rapidly become dangerous military forces. These forces clashed with both secular forces, but also with other Buddhists, including Tendai warrior monks.

The Sengoku era ended with the battle of Sekigahara and the ascension of Tokugawa Ieyasu to the role of the shogun. This led to the Edo period from 1603 to 1868, which saw substantial changes in Japanese Buddhism. The armed leagues and warrior monks were defeated, and Buddhist instituions would no longer take up arms. Another important change were the head-branch and temple affiliation systems, which required all temples to be affiliated with a government-recognized lineage and attempted to bring them under political control of the government. Furthermore, all households were forced to register as affiliates of a Buddhist temple. Certain sects were treated more favorably, while Nichiren and Jodo shinshu sects were seen as contributing to social disturbances during the Sengoku period.

The development of printing techniques and support granted by Tokugawa shogunate to Buddhist scholasticism led to a boom in Buddhist print works and studies. Buddhist temples broadened their means of acquiring funding, including sale of things like talismans, medicine, prayer petitions and posthumous names. These forms of funding persist to this day.

There were also developments within Buddhist practices and doctrines. New generation of public preachers tried new, more narrative aproaches. These even included humorous anecdotes. Development of print culture led to reinvigorated studies of Sanskrit, the language of many older Buddhist sutras. Some schools of Buddhism made efforts to move to tighter monastic precepts. The Obaku school of Zen became a late addition to Japanese Buddhism, being established by Ingen (1592-1673), a Chinese monk who fled the Manchu conquest of China to Japan.

The Tokugawa shogunate ended with the start of the Meiji restoration in 1868 which returned political power to the hands of the emperor, and saw numerous reforms patterned after Western nations in pursuit of rapid modernization. This was an era of repression of Buddhism, and of very forcefully aligning Buddhism with the state interests.

Early Meiji era saw the forcible separation of Shinto and Buddhism, starting immediatedly from 1868 onwards. There was a mix of reasons for this. The Shinto advocates saw Buddhism as a foreign element that was corrupting the Japanese spirit. Essentially, Japan was going through a kind of indigenous equivalent of the nationalist surge that Europe saw during the 19th century. There was also widespread popular resentment towards Buddhism. Many temples had abused the obligations for donations that had come with the temple affiliation system. Buddhism was also seen as backwards, contributing to Japan’s weakness in front of the technological advanced Western nations, and affiliated with the unpopular shogunate.

This popular resentment boiled over into a violent movement that went beyond the orders to separate Buddhist and Shinto religious institutions. The haibutsu kishaku movement caused the closure ordestruction of up to 40 000 Buddhist temples. In some areas, this was 80% of the temples. Land of the temples was seized, artifacts and books destroyed. Buddhist monks were stripped of their status and sometimes attacked or killed.

The most intense period of this repression lasted untill 1871. In 1872, the Meij government ended the status of Buddhist precepts as state law and allowed monks to marry and eat meat. This led over the coming decades to the Japanese peculiarity of temples becoming essentially family run. As Buddhism was on the defensive after the period of persecution, many institutions and individuals sought to reinvent Buddhism in ways that would support the Japanese national, later imperial project. This saw the emergence of many new movements pushed by lay people. Some of these aimed to align Buddhist with the Japanese national project or modernism.

Meiji era also saw the emergence of Buddhist studies in Japan, in the sense of modern academic studies. However, often the term ”indian studies” was prefered over to Buddhist studies, and Buddhism was frequently treated as a philosophy, not a religion. This was done to avoid religious Buddhism having influence over education. There were also movements seeking to integrate Buddhism with Western philosophies.

The short Taisho era from 1912 to 1926 saw further development of trends that emerged towards the end of Meiji era, including various popular movements to align Buddhism with the Japanese national project or modernity. The early Showa era from 1926 to 1945 saw a 15 year period of Japanese expansionism, starting with the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and ending with Japan’s surrender to United States in 1945. The wartime period saw the government tightening it’s grip on Buddhism, but also many of the Buddhist institutions aligning with the imperial efforts. The severe persecution of early Meiji era had left Buddhist institutions largely compliant with the state. Some were however involved beyond compliance, and saw the war as an opportunity to spread Buddhism and revitalize it in parts of Asia where it had lost influence. At the same time, veneration of the Emperor and relics from Ise Grand Shrine became obligatory. Those Buddhists who resisted these policies were ruthlessly persecuted.

Japan’s defeat in the Second World War brought large changes to the religious landscape of the country. The connections between state and religious life were largely severed, and freedom of religion was enforced on the country. This lead to emergence of many new religious movements, as well as changes within Japanese Buddhism. For example, the Houryuji temple established it’s own Shoutoku denomination. Another big trend was the emergence of fully lay operated Buddhist organizations. Buddhism faced problems post-war, including physical devastation brought by the war, changes in demographic distribution following industrialization as well as loss of trust due to complicity in war efforts, for which many Buddhist institutions have demonstrated repentance for.

From the 1960s onwards, many forms of Japanese Buddhism shifted essentially towards providing funeral services. This has been termed ”funerary Buddhism”. While it was done out of institutional necessity, some felt this left a certain kind of spiritual vacuum in Japanese society. This vacuum has been filled by various new religious movements, some of the derived from Buddhism. The rapid social and economic change during the 1970s and the 1980s ”occult boom” fueled interest in divergent forms of spirituality. Some of these became quite notorious. For example, the Aum Shinrikyo cult that committed the 1995 Tokyo sarin attacks mixed elements of Buddhism into its teachings.

In the present day, Japan has the third largest Buddhist population in the world, after China and Thailand. About 46% of Japanese identify themeselves as Buddhists, and many of the other 54% take part at least sporadicaly in Buddhist activities such as temple visits. The forms of Buddhism with most followers in this religious sense are the various forms of Pure Land Buddhism and Nichiren Buddhism, most likely because they have features that are more in line with Western ideas of religion. Some Nichiren sects are extremely sectarian and do not allow participation in other forms of religion, an anomaly in Japan where people generally freely take part in religious activities as they feel like it.

While Buddhism was in a process of decline for a while after the Second World War, there has been something of renewal of interest towards Buddhism along with Shinto in recent years. Buddhists temples have also tried various new forms of outreach, including popular culture collaborations (at least once with Touhou project), and an android preacher. These have at times caused controversy, and there has also been – once again – debate about whether Japanese Buddhism so move towards stricter precepts and be reformed away from Mahayana ideas.

To some extent all of Japan’s Buddhist heritage has shaped Touhou. The motifs of less than perfect Buddhist clergy and dangers of religious corruption or coercion are very much motivated by the real-life failures of religion in Japan. However, Touhou’s treatment of Buddhism isn’t all negative either. Certain elements of Japanese Buddhist culture simply matter-of-factly exist in Gensokyo. Byakuren’s attempt at bringing the dharma to youkai reflects broader Mahayana tendencies at seeing all beings worthy of salvation, as the efforts how those in Japan who sought to tend to the needs of those who were considered ”nonhuman”. Matara Okina originally creating Gensokyo as a refuge for the discriminated also reflects the humane side of Japanese Buddhism.

While Touhou does draw in a lot from general Japanese Buddhist culture, there are three schools in particular which are referenced to in Touhou. These are the Shingon, Tendai and. Zen The Shingon and Tendai sects heavily shaped medieval Japanese religion, culture and mythology. The Myoren temple crew is based on a Shingon legend, while Matara Okina is based on a deity that was heavily featured in medieval Tendai, albeit escaping it’s confines. The character of Nippaku Zanmu is based on a historical Zen monk, there are some potential Zen connections in the Wild and Horned Hermit manga, and ZUN has in later years stated that Byakuren is a Zen monk.

Beyond these more sectarian forms of Buddhism, Touhou also references the popular Shoutoku faith. In Japan, Prince Shoutoku is widely revered as a boddhisattva, and while ZUN presents the ”legend of Prince Shoutoku” as Taoist for reasons which will be explored later, even his depiction includes some elements of the Buddhism that grew around Prince Shoutoku’s legend. Touhou also contains numerous elements from inter-sectarian and folk religion aspects of Japanese Buddhism.

Shingon

As stated before, Shingon Buddhism is a sect of Vajrayana or esoteric Buddhism. In this context the esoteric refers to three things. First, it refers to the idea that the masters of Shingon Buddhism possess an unique understanding of Buddha's true message that can be transmitted only through oral tradition that is revealed to initiates who are considered ready to receive it. Secondly, it refers to the use of ”Three Mysteries” of mudra (hand gestures), mantra (sacred utterances) and mandala (visual spiritual tools). Thirdly, it refers to the idea that various Buddhist teachings have an exoteric, outward-facing aspect and an esoteric aspect that requirest particular knowledge and practice to understand. The exoteric elements of teachings are considered to means to teach the dharma to those who do not yet have the capacity to understand the esoteric elements.

While Shingon shares certain elements with Himalayana Vajrayana Buddhism, it lacks the most transgressive elements of Himalayana Vajrayana such as the use of sexual tantric practices or charnel ground practices. This is because Shingon is based on early Indian Vajrayana, and the form of Vajrayana that became disseminated into Tibet is based on later Indian Vajrayana. Shingon cannot however be understood as an early or ”primitive” form of Vajrayana. Kukai, the monk who established Shingon in 816 made considerable philosophical and practical innovations, synthesizing elements from a broad base of Mahayana and Vajrayana teachings. And while there are less outward-facing sexual elements, medieval Shingon made use of symbolism alluding to human sexuality, reproduction and gestation. Shingon also shares with Himalayan Vajrayana the idea of transmuting baser desires into more enlightened ones through spiritual practice.

The central aim of Shingon is to achieve ”Buddhahood in this very body”, or enlightenment in a single lifetime. The practice of the Three Mysteries is thought to accelerate this process. This enlightenment is in Shingon context considred becoming one with Mahavairocana, or Dainichi Nyorai, the Cosmic Sun Buddha, named so because its presence is thought to pervade everything like sunlight does. Dainichi Nyorai is seen as the dharmakaya, ”truth body”, an universal, primordial Buddha who constitutes the basis for all phenomena, or is all phenomena. It is formless, omnipresent, self-existent, eternal, indestructible, unable to be defiled and the source of all manifestations.

In other words, Dainichi Nyorai is the universe itself. As Shingon conceptualizes the mind to be one of the six elements that make up the universe – and thus Dainichi Nyorai – Dainichi Nyorai has been sometimes at least in popular understanding conceptualized as being or having a kind of cosmic consciousness. This interpretation likely lend its name to Byakuren’s theme song Emotional Skyscraper – Cosmic Mind. Another term that appears in Undefined Fantastic Object, Hokkai or World of Dharma, might have it’s origins in Dainichi Nyorai too. One of the attributes given to Dainichi Nyorai is the ”Wisdom That Perceives the Essential Nature of the World of Dharma”. More explicitly, in the various games, Byakuren has several spellcards directly referencing Mahavairocana.

The heavy focus on esoteric teaching, use of mudras, mantras, mandalas and rituals have sometimes led to Vajrayana Buddhism being conceptualized a kind of ”magical” form of Buddhism. While one religions rituals are another one’s magic, this isn’t an exactly wrong interpretation either, as these practices attempt to effect a change in the world through spiritual means. While Shingon practices these days are mostly about the pursuit of awakening and the cultivation of boddhicitta, compassionate mind that works to further the enlightenment of others, historicaly Shingon practitioners did also perform practices for more worldly ends. They prayed for the health and safety of the emperors, performed acts of spiritual purification and protection, conducted rituals for worldly benefits and even prayed for the surrender of enemy nations during the Second World War. An element of this that lingers is the goma fire ritual. During this ritual, a Shingon practitioners burn wooden boards that have prayers written on them in a fire pit usually dedicated to the deity Fudo Myoo. While it has an element of spiritual cultivation and eradication of obstructions and delusions, the lay participants are allowed to ask for worldly benefits.

Touhou’s main connections to Shingon come from the game Undefined Fantastic Object and the characters associated with Myoren temple. In particular, these connections are inspired by the tales of the Shigisan Engi Emaki, and the Chougosonji temple that houses this picture scroll.

These tales tell of the miraculous deeds of a monk called Myoren, and Hijiri Byakuren is a fictionalized version of his sister, which is featured in one of the tales. In the story as it is told in Shigisan Engi Emaki, the nameless sister of Myoren, a Buddhist priestess is worried for her brother. In her dream, the priestess sees a vision of Daibutsu and a purple cloud alongside a mountain. This is a sign to her that Myoren will return safely. One might remember one of Byakuren's spell cards, Omen of Purple Clouds and see the connection here. Purple is thought to be associated with spiritual growth and powers more broadly in Japanese and Chinese culture.

Byakuren’s surname hijiri comes from a class of itinerant Buddhist preachers known as hijiri, or ”Holy Ones”. They were ascetics who came from Shingon or Tendai backgrounds, but retired from temples into the wilderness and mountains, where they intensively studied and recited holy texts. Some were oriented towards the Lotus Sutra, some towards Pure Land practices. This ascetic practice was believed to give them supernatural or holy powers, which included the power to subdue malignant spirits. Ideally these spirits could be made to understand the dharma, and therefore make them use their powers for enlightened and compassionate purposes. This idea is an extrapolation of the idea that base desires could be transmuted into more enlightened ones. Byakuren preaching specificaly to youkai, though initially for selfish reasons, is a playing on these themes. Another potential reading on Byakuren becoming immortal via youkai is a cynical take on how religion needs "the unknown" and "monsters" to survive, as much as people might try to make these things "pass into fantasy". In later works, ZUN has certainly offered views along these lines.

Byakuren's holiness is a hotly debated topic among fandom, but her aims and actions are more in line with Mahayana thinking than a lot of people involved in these debates realize.

While Byakuren’s surname comes from the hijiri, she is described as being a magician whose repertoire include abilities not derived from Dharma, or orthodox forms of Buddhism. This to some extent reflects real-life medieval Shingon occasionally developing into forms that were considered ”heterodox” or ”heretical”. Often these included reverence of various devas or entities that walked the line between devas and demons for worldly gains. The idea between rituals involving devas or potentially troublesome entities was that since they were closer to the material, human world, they could be used to better to induce change in material reality. This was seen as risky and something that alienated people from Buddhism’s ultimate aims of liberation from samsara. Still, various rituals for things like love and subjugating enemies were performed for the patrons from nobility and warrior classes. There’s a kind of strand in contemporary Japanese thought that sees the decline of Shingon coming from practicing ”dark magic”, an exaggeration of historical fact. This kind of thinking likely influenced Byakuren being depicted as magician, as well as Hokkai being accessible through the demon-world Makai, and Byakuren’s spellcard ”Devil’s Recitation”.

Another prominent member of the Myoren temple is Shou Toramaru, who is very likely inspired by the Chougosonji temple. This particular Shingon is dedicated to the dharma guardian Bishamonten, and is filled with iconography related to tigers. This is because according to legends, the temple’s site is where Bishamonten first made himself known in Japan on a day of the tiger during the hour of the tiger. While Bishamonten is widely revered outside of Shingon, he does have a strong association with Shingon through the Chougosonji temple.

Bishamonten or Vaisravana is one of the Four Heavenly Kings, and the ruler of the northern quadrant of the universe. He is the king of yakshas, a type of nature spirits which are often depicted as troublesome ogres. He is a protector of Buddhists, punisher of evildoers and a god of warfare. Because of his association with the northern direction, which is in East Asian culture associated with wealth and sovereignity, he is also seen as a deity incorporating these features in popular religion. As such, he has left strictly Buddhist context and is one of the Seven Lucky Gods. While Bishamonten is compassionate, he is also depicted as being something else than a fully-fledged boddhisattva, and legends tell of him not only using violence on those threatening Buddhism, but also punishing Buddhists who fail to uphold their promises.

Shou is described as the ”tiger-striped vaisranava”, and is a discipline or avatar of Bishamonten. In a way she outranks the leader of the temple, Byakuren. Shou’s design has many common elements associated with Bishamonten, including the pagoda and a spear. While she does uphold Buddhist ideals, she is also less than perfect follower of the Buddhist precepts. This is likely influenced by Bishamonten’s reputation of being a more ”worldly” being. Shou’s spellcards contain references to the mythical weapon vajra. The vajra is a form of a ritual tool, but it also serves as a metaphor for sudden enlightenment. It’s from this where the ”vajra” in Vajrayana comes from.

Another character associated with Bishamonten is Nazrin, though the association is much looser. ZUN said that since the Mouse of Chinese Zodiac is associated with North, just as Bishamonten is, it would make sense that Bishamonten would have a mouse servant. In Chinese culture, the direction of North was associated with sovereignity and wealth, and Nazrin being a ”tiny commander” who finds treasures fits these themes.

The character of Kumoi Ichirin may also have an association with Bishamonten via Shigisan Engi Emaki. One of the stories features a flying messenger of Bishamonten called Ken no Gohou who flew on a wheel and was followed by clouds or winds. It's also possible that her depiction was influenced by a story about a buddhist rosary becoming alive as tsukumogami called Ichiren Nyuudou A prominent source of inspiration for her character are tales about the Nyuudou youkai masquerading as monks and how to defeat them by using one's wits. Ichirin's appearance, especially her original appearance in UFO, is influenced by real-life garb of Buddhist nuns in Japan.

As for the two last members of the Myoren temple, Minamitsu Murasa does not have quite a direct Shingon or Buddhist association. Tales of ghost ships however are a trope in Japanese culture, and there is a wide tradition of various Buddhist figures running into trouble at sea, and then being rescued by some Buddhist deity or another. Byakuren subduing a ghost ship youkai is potentially a subversion of these type of stories. The very founder of Shingon, Kukai, faced perils at sea. It's because the expedition that took him and Saicho into China ended up drifting apart because of terrible weather, with not all ships making the journey, that the two ended up in different parts of China, studying different forms of Buddhism in the first place. Perhaps some of those ships lost at sea ended up contributing to Japanese legends of ghost ships...

Houjuu Nue does not have a direct Buddhist association either, being based on the Nue youkai. However, her ability to create ”Seeds of Unknown Form” that cause things to assume an illusionary appearance that looks different to every observer based on their projections is an extremely Buddhist idea. Buddhism likes to compare the everyday perception of things to illusions. This isn’t to say reality is somehow ”unreal”, but rather that people constantly project judgements and assumptions onto reality. A good example is this how different the whole world appears when one is in a great state of grief, anger or joy.

The Chougosonji temple is also a likely reason why Toyosatomimi no Miko's senkai ends up under the Myoren Temple. That particular temple is said to be founded by the historical Prince Shotoku, on whom Miko is based on. Another possibility is some kind of strange commentary on the influence of Taoism on East Asian Buddhism.

Tendai

Tendai is Japanese school of Buddhism based on the Tiantai lineage from China. Founded by Saicho in 806, Tendai attempts a grand synthesis of various Buddhist practices and ideas that existed during the time of it’s founding. In Tendai, this is called the Four Integrated Scools, which are meditation, Pure Land practices, tantra and Buddhist precepts. The integration of tantric elements means there exists an esoteric dimension to Tendai. However, unlike pure esoteric Buddhism, Tendai doctrine sees all paths towards awakening as valid. Rather than being a question of supeority or infeority, it’s a question of what is suited to which circumstances. Tendai Buddhism emphasizes the importance of the Lotus Sutra, a foundational Mahayana Buddhist sutra, and writings of the Chinese Tiantai patriarchs. Out of these patriarchs, the works of Zhiyi are considered of particular importance. Zhiyi is considered an exceptional systematizer of Mahayana Buddhist thought, who interpreted the Lotus Sutra as the central Buddhist text that would provide a framework for understand all the other texts.

The Lotus Sutra is a foundational Mahyana sutra that includes several key features of Mahayana Buddhism. These include the idea that all Buddhist teachings and practices eventually lead to Buddhahood, the concept of skillfull means, the potential for all beings to awaken, that the historical Shakuyamuni Buddha was a manifestation of an immeasurably older, vaster, undying buddha that achieved enlightenment countless aeons ago, and an expanded cosmology and pantheon.

When it comes to all Buddhist teachings and practices eventually leading to the same end, the Lotus Sutra treats these as skillfull means or upaya. This means that they are teachings that are tailored to suit particular people. There’s widespread metaphor of an ideal Buddhist educator as a skilled doctor who can diagnose the ”patient” and give aproriate medicine. This isn’t to be understood in a manipulative sense, but rather that different people have different kinds of apparent needs and hopes, which can be revealed to align with the Buddhist path. Fundamentaly, this is derived from the idea that the experience of samsara is universal, but the particular ways it is experienced are unique. One can of course make cynical readings of upaya, and this is actually done in Touhou, where Toyosatomimi no Miko offers a very manipulative view of the idea.

In the context of Lotus Sutra, skillfull means are in particular expressed through the ekayana doctrine. Here, it is specificaly the paths of the discipline (including lay people), the solitary buddha (one who achieves awakening without teachers) and the path of the bodhisattva which are thought to form the ”ekayana”, the ”one vehicle” which eventually leads all to buddhahood. This doctrine very likely influenced the later Tendai project of grand Buddhist synthesis. The various divergent forms of Buddhism that emerged could be conceptualized as different forms of the three paths which ultimate are just a single vehicle to awakening.

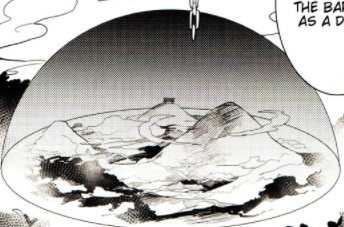

The Lotus Sutra posits that all beings have the possibility of reaching true buddhahood, and this was a clear break from earlier views on Buddhism which saw this as an exceptionally rare event, and that each age would only have a single buddha. In Lotus Sutra, there are multiple buddhas and boddhisattvas active in the world, and in the Lotus Sutra sense the world is a breathtakingly massive cosmos sometimes interpreted as a kind of multiverse that also incorporates the layered upper and lower realms of earlier forms of Buddhism. The buddhas and boddhisattvas described in the Lotus Sutra include celestial entities operating outside the cycles of death and rebirth, but still able to reach into the world of samsara to teach, guide and help other beings. These beings have their own buddha-fields, kind of parallel worlds or pocket dimensions where practice of Buddhism is easier than in the Human Realm.

Lotus Sutra turns Buddha preaching his final teaching on the Vulture Peak into a multiversal event that spans all of time and space. Shakuyamuni Buddha is revealed to be a manifestation of a kind of cosmic buddha that achived enlightenment an innumerable aeons ago. It’s revealed there are countless buddhas manifest throughout all of time and space as a kind of flow of this eternal buddha. This interpretation has rather notable parallels with Mahavairocana Sutra where the ageless, timeless Vairocana Buddha is the basis of all existence and all manifestations.

An important chapter of the Lotus Sutra is chapter 25, where the boddhisattva of mercy Avalokiteshvara, also known as Kannon Bosatsu in Japan, reveals that it is capable of taking any form conceivable to teach and help other beings. This is an extreme expansion of the idea of skillfull means, opens up the possibility of learning dharma from every encounter with a sentient being and that the reader themself might act with qualities that manifest the work of Avalokiteshvara, become a manifestation of Avalokiteshvara in certain times or place. This chapter also quite likely influenced later Buddhist ideas about various buddhas and boddhisattvas manifesting as different types of entities.

Tendai Buddhism developed the idea that there exists an exoteric as well as an esoteric reading of the Lotus Sutra. While Tendai-specific texts related to the matter remain untranslated and highly inaccessible, the idea of there being a kind of "hidden" meaning to Lotus Sutra has influenced many different takes on the sutra's themes. For example, there exists an interpretation regarding the buddha-fields that rather than being entirely separate from the everyday reality, they are in some sense immanent in it, as inaccessible a place without decay, danger or suffering might seem from the everyday point of view. There also exists a kind of esoteric interpretation of the lotus Sutra as a whole, owing to the immense themes of the sutra as well as it’s structure. In this interpretation, the Lotus Sutra as it is written in text is seen as an "introductory text", and that life itself is the real Lotus Sutra.

The Lotus Sutra is considered an important sutra by all Mahayana schools of Buddhism, but it’s specially popular and influential in Japan, owing to Tendai Buddhism seeing it as the single most important Buddhist sutra and Shakuyamuni Buddha’s final teaching. Nichiren, who initially studied Tendai but went on to become the primogenitor of his own lineage of Buddhism, saw the mere recitation of the sutra’s title as approriate practice. Because Tendai was extremely influential and the Lotus Sutra was also an important text for Shingon, the influence of this sutra completely infused Japanese culture.

One way that this shaped Japanese culture and which is related to the teachings of Tiantai patriarch Zhiyi is the idea that certain places in material reality were also part of other realms of existence. Zhiyi advocated an idea known as 3000 Realms in a Single Thought-Moment, which basicaly states that all the ten realms of existence are completely interpenetrating, existing as not only literal and physical realms, but also realms within realms and as states of mind or existence you can go into. For example, a human can fall into a hellish or animalistic state and in a sense go to hell or animal realm on this very Earth. Of course, it’s also possible for a human to go into a deva-like or even enlightened state. And for a deva to go to a hellish state, a demon into a deva state and so on…

This idea of realities intermingling with each other found a physical interpretation in Japan. Some sacred mountains were seen as replicating the entire ten-layered cosmos, and certain valleys and dry riverbeds were seen as manifestations of hellish realms on Earth. There were even extraordinarily holy places which were considered as pockets of buddha-realms on the Human Realm. The very idea of Gensokyo as a kind of pocket dimension that however still mingles with Outside World is very much in line with this thinking, though Gensokyo is harder to place directly onto Buddhist cosmology. In a Buddhist framework it’s perhaps best interpreted as a more magical version Human Realm, where the distance to other realms is shorter.

The biggest, most direct Tendai-related reference in Touhou is the character of Matara Okina. She is based on a deity known as Matarajin, that while not exclusive to Tendai, was heavily associated with this school of Buddhism in medieval times. The way Matara Okina is depicted in Touhou is also much more in line with how the historical Matarajin was depicted in Tendai, as opposed to the three-headed yaksha ogre he was depicted as in Shingon.

Praised be the Hidden Star.

Matarajin deserves a much longer writeup of his (or her – there are indications he might have originally been a she) own, but to offer a brief overview, Matarajin was a deity associated with obstacles, destiny, stars and also the performing arts. Over time perception of the deity shifted greatly, and he developed a popular faith of his own that came eventually be declared heretical. While many medieval Japanese deities underwent drastic changes in identity and perception, Matarajin stands out because his origins are exceptionally murky. He’s neither an indigenous Japanese deity, nor from established Buddhist canon. It has been speculated that the deity might have originated from Korea or China. As Matarajin seemed to integrate influences from both Buddhism and outside of it, this section will go over details relevant to Buddhism.

The initial appearance of Matarajin was a kind of demonic deity of obstacles who would obstruct rebirth into Pure Land unless placated. However, when placated, he would become a protector of Buddhist practice, in particular the recitation of Amida Buddha’s name, and the places where this nembutsu was performed. In particular he was thought to guard and protect the ushirodo, the ”backdoor area” behind the honzon or main image of Buddha Amida. This role of protection within the Tendai sect was eventually extended to the Tengu warding ritual, tengu odoshi, that is referenced to in Touhou in rather straightforward manner. However, in history it was a bit unclear if it was about trying to suppress or to placate the Tengu. Matarajin might have also been seen as a kind of Tengu that had to be appeased.

He was however also seen as a pestilence god. This likely came through association with the matrikas, highly ambivalent female deities of Indian origin who were seen as embodiments of nature’s capacity for creating and taking life. This ”taking” also included epidemics. It’s indeed from these matrikas that Matarajin’s name comes from – the name essentially means ”god of matrikas”. Another potential origin for Matarajin’s name is the Indian deity Mahakala – known as Daikokuten in Japan – who subdued the dakinis, human-lifeforce eating spirits that are sometimes seen as hostile manifestations of matrikas. It’s unsurprising that Daikokuten is one of the deities associated with Matarajin.

As the matrikas were associated with the Pleiades and the Big Dipper, Matarajin became associated with the Big Dipper. The association with Big Dipper brought an association with Myoken Bosatsu, the Buddhist personification of North Star. This astral association intertwined with earlier ideas of Matarajin as a deity of obstacles to create the idea of Matarajin as a deity of human destiny. He became seen as a koujin, a type of deity that ”covers the human like a placenta covers the fetus”, an entity that follows one throughout the whole life. Matarajin’s appearance became that of an old man with two attendants. He became associated with the performing arts, particularly the noh character of okina, old man, who is a kind of generic stand-in for ancestral kami.

This non-exhaustive list of Matarajin’s various associations and shifting perceptions should not be taken as a linear description, but rather it’s likely that the various elements that constituted his identity were present in different ways in different contexts where he was revered. While Matarajin being a deity that had characteristics that can be described as malevolent attracting popular worship seems confusing, it’s good to keep in mind that Japanese religion has always assumed that deities have both benevolent and malevolent characteristics. Even the merciful boddhisattva Kannon has wrathful manifestations.

In Matarajin’s case his obstruction of reincarnation into Pure Land became seen as a kind of enabelement of this reincarnation. The earlier unsavory liver-eating that the demonic Matarajin was associated with turned into consumption of human impurities and impediments. Because Matarajin’s threat to obstruct rebirth into specificaly Buddha Amida’s pure land seems to circumvent the promise of a much mightier being, Matarajin eventually became in some circles to be seen as a wrathful manifestation of Buddha Amida.

This opens up a deeply fascinating possibility regarding the origins and purpose of Gensokyo. In an interview ZUN descriped Matara Okina as the original creator of Gensokyo, who created it as a refugee for discriminated people. As Buddha Amida is capable of creating an entire world of his own, it opens up the possibility that his wrathful manifestation could create some kind of a ”wrathful pure land”. While no such concept exists in canonical Buddhist sources, there are ideas regarding various degrees of pure lands, and that pure lands can be entangled with and manifest in other realms.

The Matarajin of our world lost popularity after being denounced as a heretical deity. This was partly because Matarajin was part of a failed political play that the Tendai priest Tenkai (1536-1643) attempted. He established the Toushogu shrine and temple complex at Nikko which enshrines the deified version of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the warlord who unified Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate. To protect the Tokugawa shogunate, Tenkai enshrined Matarajin and Sanno, another Tendai deity. Matarajin was in this context seen as a kind of deity of rulership, and his origin might have been as deity worshipped to protect the birth star of a ruler. By enshrining these deities, Tenkai sought to provide the shogunate with a revised Buddhist ideology and to shift the Tendai center of power closer to the new secular power center of Edo. The failure of this play likely contributed to the criticism of Matarajin faith. The critics of the faith were given support by Hekija Hen, a treatise by Reiku Koken (1652-1739) that condemned initiation rituals practiced by Matarajin worshippers. These were said to include sexual explicit elements and antinomial elements. However, little actual evidence of orgiastic elements being involved exists. Whether there is truth to this or not, the opposition led to Matarajin worship being banned at the main Tendai temple complex at Mt. Hiei and Matarajin being pushed to the margins.

There is one more interpretation of Matarajin worth mentioning, as it relates both to themes of Touhou and ties together the various identities and function he acquired during the course of history. That is the role of Matarajin as a dream king, a Buddhist deity that would grant dream visions. Documents discovered in Togakushi, Nagano, revealed that in Tendai Buddhism Matarajin was also treated as one of such dream kings. A particular role of the dream king was the present confirmation for the right to undertake the vaipula samadhi ritual. The idea of the dream king comes from the Golden Light Sutra, where boddhisattva Shinso dreams of a shaman beating a golden drum, the reverberations of the drum revealing wondrous visions of the ten realms. This interpretation of Matarajin as dream king has been in modern times suggested as a way to tie his multiple roles: he inspires dreams of religious visions to priests, imaginative dreams to inspire entertainers and dreams to inspire rulership and new mythologies to bring the people together for rulers. Video games would definitively go to the category of entertainment, and interestingly enough Togakushi is in Nagano where ZUN lived his childhood.

Very little of the Matarajin faith remainds to this day, but it’s still possible to pay your respects to him at the nembutsu hall in Nikko Touhoushogu. In addition, the Motsu-ji temple has a hidden statue of him, and the Koryu-ji temple is still associated with him, even though the Ox Festival once dedicated to Matarajin is no longer performed.

Matarajin’s ambivalent nature, shifting perception, changing representation and at times total reversal of roles from a troublesome demon to a compassionate being are representative of the highly mutable nature of medieval Japanese religion. And if one is to place their faith in such things, perhaps it is a story of an entity changing it’s nature. After all, Buddhism does not believe in eteternal unchanging essences, not even for yakshas.

When it comes to Matarajin, Touhou has caused things to pass out of fantasy. There’s a book called Matarajin of Darkness: Pursuing the Myster of the Changing Gods. Some among the Japanese Touhou fandom speculated that the cover of the first edition might have influenced the cover art of Hidden Star in Four Seasons. The release of the game caused the first edition to be sold out. The 2nd edition added the subtitle ”The Ultimate Absolute Secret God!” and a new afterword that shows the staff and author are aware of Touhou and it’s impact on the book’s sales. Beyond this, Touhou caused a tiny revival of the Matarajin faith, as multiple people have conducted pilgrimages to sites that are still associated with him, some even acquiring the exceptionally hard to get ofuda of him.

Zen

Zen is a form of Japanese Mahayana Buddhism that has become very popular outside of Japan. It’s quite likely you have in some way or another heard of it. Often the Western representation of Zen has been incomplete and distorted, and it’s highly likely that whatever preconceived notion you have of Zen isn’t quite right. While Zen doesn’t have a very large footprint in Touhou and what is to be found is rather scattered, it’s still has a presence. As Zen is very popularly misunderstood, this is also a good opportunity to straighten out some misconceptions.

Zen is the Japanese evolution of Chan Buddhism, which developed in China during the Tang dynasty of 618 to 907. The potentially legendary, possibly real Bodhidharma is regarded as the founder and first patriarch of this form of Buddhism. He was an iconoclastic figure who denied the possibility of acquiring karmic merit by doing things such as building temples, emphasizing that the only way to enlightenment was through practice. This idea carries on the Zen to this day, and Zen is distinctive for it’s extreme focus on meditation practice.

Chinese Chan synthesized madhyamaka emptiness philosophies with the Yogacara mind-only philosophy, and was also most likely influenced also by Taoist thought and meditation practices. For example, the emphasis of putting attention to the hara, a point int lower stomach correlating to the lower dan tien in Taoism, is of most likely Taoist origin. Chan, later Zen, also tend to hold the view that the true nature of reality can only be experienced, and that even the best of descriptions of it are merely a description, an incomplete picture. This is very reminescent of the Taoist idea that the true Tao (the way things are) cannot be described, only experienced.

Because the true nature of reality is seen as something that can only be experienced, Zen tends to disemphasize elaborate conceptual constructs and very heavily emphasizes practices intended to foster this experience of the true nature of reality. The Zen idea of awakening as something that can be reached through practice (or sometimes spontaneously), but which once acquired is not some permanent transformation or transcendence but something that must be maintained and cultivated. This is perhaps the most ”accessible” Buddhist conceptualization of awakening. In a way, while Shingon aims for ”Buddhahood in this very body”, Zen aims for ”awakening in this very decade” – though naturally how long it would take for one to experience such depends on myriad factors.

While other schools also tend to make distinctions between different "levels" or "types" of awakening, Zen is notable for the idea that insight into true reality, kensho or satori, is usually extremely fleeting and must be honed with practice. Many people can stumble into some kind of a kensho and not even realize what is happening. History of Zen knows of people spontaneously getting their first state of Kensho when grappling with the big questions in life, often in the fits of some kind of existential crisis, sometimes even as children. There are also accounts of people experiencing some kind of kensho with minimal Zen practice, or even just exposure to Zen ideas. However, in the Zen view, achieving a brief kensho can be detrimental, as it can lead to slackening of practice and increase in egocentric notions following an exceptional experience. In contrast, the Zen term for final, absolute awakening, the kind of historical Shakuyamuni Buddha is said to have achieved is daigo-tettei or "great awakening".

When it comes to Zen terminology, satori is also used in other contexts for "knowing", as it's derived from the verb satoru, "to know". It's a bit unclear whether the everyday term or Zen concept inspired the Satori youkai that the Komeiji sisters in Touhou represent. Historically, all kinds of supernatural powers were attributed to advanced Buddhist practitioners (Zen itself tends to downplay these aspects though). The Zen idea of "mind-to-mind transmission of teaching" could have roused all kinds of telepathic interpretations. This could have contributed to the naming of a mind-reading youkai after a specificaly Zen interpretation of satori.