Taoism

The Seitenkyuu temple traces it's origins to the mysterious ancient past of 1995.

Taoism was historicaly more of an influence rather than an organized religion in Japan.

Taoism is a belief system of Chinese origin that incorporates elements of religion, philosophy, medicine, self-development, craftsmanship, astrology and magic. While Asia historicaly had much less stark division between things the West would regard as separate disciplines or fields of life, Taoism is exceptionally holistic in it’s aproach to existence. In a way, Taoism can perhaps be summed up as a ”way at conceptualizing how reality operates”. It's the third spiritual tradition present in the world of Touhou. In the outside world, the religious aspects of Taoism have had a much smaller presence in Japan than Shinto and Buddhism. However, the various other aspects of Taoism have had a notable impact on all of East Asian culture, Japanese culture included. These are such archaic and powerful cultural influences that they have seeped to the level of very language and worldview.

These days, there exists a conceptual division between philosophical and religious Taoism. While this division has been criticized, as the ”philosophical” elements are also present in more religious forms of Taoism, there is some merit to it. Early Taoist texts largely lacked liturgical elements and explicitly supernatural ontology or references to particular deities. This allowed Taoism to be adapted to different cultures and circumstances, sometimes as a philosophy, sometimes as a set of practices, sometimes as a religion and sometimes as all of this and more. While Taoism is very diverse, common goals in it include self-cultivation, deeper appreciation of the Tao and a more harmonious existence. It’s also in a sense rather undemanding system, as one does not have to engage with religious Taoism to for example practice Tai Chi or use the I Ching divination system. This has allowed Taoism to travel far and many are engaged in practices influenced by it, while being only dimly aware of what Taoism even is. So perhaps one could split Taoism down into even further categories, starting with ”practical Taoism” that is not so interested in either religion or philosophy...

Sometimes the history of Taoism has been represented as an arc where it starts as a philosophy seeking harmony with the way things are, and then slowly ”degenerates” into withcraft, superstition, religion and trying to hassle with the order of nature. I don’t find this kind of narrative convincing, as even the earliest forms of proto-Taoist practices were tied with spiritual practices of the day and trying to affect change on reality through them, namely shamanism. There is however a kernel of truth that over time Taoism became more elaborated on, systematicized, and developed elaborate religious orders, cultivation practices and a staggeringly vast textual corpus of canonical texts. Taoism has kept evolving, and it’s all-encompassing nature has allowed for interpretations that range from philosophical to religious to ideas that defy easy Western categories. Perhaps like the Tao itself, the Taoism that can be described is not the real Taoism. One has to go and see it’s lived multiplicity to get a glimpse of it.

As Taoism has been intertwined with other forms of Chinese thought and Buddhism for centuries, it can be at times very hard if not entirely artificial to try to cut apart Taoism from broader strands of Chinese thought. Are yin and yang a core Taoist concept, or a broad Chinese cultural idea that became core part of Taoism? Did Taoism influence Chinese folk religion, or did Chinese folk religion influence Taoism? Where do the limits of ”religion”, ”philosophy” and ”culture” lie in a culture that had most likely rather different ideas regarding these compared to the present day Western context that I am writing from?

These are difficult questions that pose a very hard practical problem for trying to write about the influence of Taoism on Touhou. This is because Taoism did not arrive into Japan as a mass religion, but rather as diffuse influences deeply intertwined with the broad wave of Chinese culture starting from the 5th century onwards. It might be entirely wrong to speak of Taoist influence on Japanese culture, and it’s fair to characterize it entirely as ”Chinese influence”. However, there is a reason to attempt to untangle some of these threads. First off is of course that Touhou treats Taoism as a separate influence on Japanese culture. Secondly, there are some very explicitly Taoist things that did end up influencing Japanese culture, some of them being rather archaic layers of Japanese culture.

As Touhou draws very broadly from Japanese culture, it has ended up referencing a surprisingly large number of things of Taoist origin or influence. Some of these influences are obvious and have been staring us at the face from the first game onwards, such as the game’s prominent use of yin-yang iconography. Other influences are considerably more murkier and at times rather surprising. The road to uncover these influences must start from somewhere, and the history and core ideas of Taoism shall server as a natural starting point.

History and core ideas

Taoism traces its existence to ancient times. It was born out of Chinese folk religion, shamanism and the observations regarding the working of natural systems, the the human body and society. Over time these beliefs and observations became codified into written works. Tao Te Ching is widely considered to be the foundational work of Taoism. It describes the Taoist worldview and the ideas of the Tao, effortless action and te, virtue. Oldest known portions of it are from the 4th century BCE. This work is attributed to the possibly mythological Laozi, ”old master”. Zhuangzhi is another foundational work, written in the late Warring States period (476-221 BCE). The text seeks to illuminate arbitrariness of dichotomies and praises human freedom and following nature. This text is attributed to Zhuang Zhou. Neiye, from 2nd century BCE contains the earliest known references to Taoist meditation and the various life and spirit energies of qi, jin and shen.

Taoism takes its name from its central concept, the Tao. This term can be translated as ”the Way”. In Chinese, it’s still used in its literal meaning to signify “road”. It has been described as the natural order that enables everything to exist and as ”the most abstract concept”. It can be seen as the source of all existence, unnamable mystery, all-pervading sacred presence and the universe as a cosmological process. Tao Te Ching famously opens with ”the Tao that can be named is not the true Tao”. Indeed, the exact nature of this ”dark, indistinct, obscure and silent” idea is thought to be impossible for humans to name or fully comprehend. Instead, the Tao can be observed by observing its myriad manifestations, including the observer themself. It can be seen in the rhythms and patterns of the natural world. Change is seen as the fundamental nature of all things, and it's the Tao that enables and manifests in these changes.

Te, often translated as ”virtue” or ”internal character”, is another important Taoist concept. As most Taoists see human nature as inherently good, this te is thought to emerge from living and cultivating the Tao. Te can include more conventional ethical virtue, but also a kind of sagely, spontaneous virtue that comes from wu-wei, effortless action. Action is seen to be effortless when it's not against the Tao, the nature of things. In practice this includes things like letting go of egoistic concerns and forceful, disruptive methods that cause tension. Instead, gentleness, adaptation and ease are to be followed. Taoist ethics treasure effortlessness, naturalness, spontaneity and simplicity. Taoism also has its own ”three treasures” of compassion, frugality and humility.

Taoism would over time incorporate observations from nature and the human body, leading to Taoist concepts related to astrology, medicine and meditation. Over time efforts were made to turn this into a systematic worldview built around different types of energies and the ways they are patterned. The ideas of the patterning of energies, their correlations and how these could be influenced practices we would consider spiritual and magical such as divination and spellcraft.

Through Taoist attempts at systemizating the patterning of energy, these different fields became interlinked with each other in ways rarely seen in other systems of spirituality. The ideas of yin-yang, the five Wu Xing phase changes, and the trigrams of the Bagua, the hexagrams of the I Ching and various forms of energy act as conceptual links and correspondences between these various fields.

Later Taoism would see the various sources of these energies as being personalized by different kinds of deities. As Taoism intermingled with the Chinese imperial system and folk religions, a rich Taoist pantheon mirroring the imperial bureacracy, but also featuring some unconventional figures, emerged. Because it was believed that the various life energies could be purified and cultivated, the pursuit of spiritual immortality, becoming one with the Tao, and ascending into a kind of godhood, became the highest aim for the more esotericaly-minded Taoists. We will explore these ideas in more detail next next.

Emanations, patterns and energies: from wuji to bagua

There are forms of Taoist explanations for the birth of the world that are emanationist in nature, describing how the functioning of the universe in the broadest possible sense, the taiji, proceeds from a kind of infinite singularity to the ”myriad beings” which define the world as we perceive it to be. In the beginning there is wuji, the non-polar all-encompassing infinity. The wuji gives rise to yin and yang, two opposing yet complementary forces that serve as the basis for further patterning of energy, matter and interactions. Yin is associated with things like passivity, retraction, contraction and darkness while yang is associated with their opposite: activity, repelling, expansion and light. These two forces are interconnected and exist in a kind of active, opposing balancing act. They can be conceptualized as two polarities of energy, sometimes even called the ”negative” and ”positive” energy. When one of these forces reaches its peak in some phenomena, it begins to dwindle. An easy to understand example would be the fact that after the sun reaches its peak during the day, it starts to set.

Often yin and yang are also thought to represent feminine and masculine qualities, but some strains of Taoist thought see that all humans can manifest either of these qualities. Others see men as having an external yang essence, but an internal ying one, and vice versa. Yin and yang are frequently referred to with the symbol ☯ , but this symbol, instantly recognizable to all Touhou fans, is actually a simple taijitu, taiji diagram, depiction of the universe encompassing both it's dual and monistic features.

Touhou frequently uses a white and red version of the symbol. These colors are considered lucky in Japan, and it’s said that the origin for this is a legend about the birth of emperor Oujin. It’s said the red and white clothes fell from the heavens when he was born. A deeper origin for these being considered lucky might come from medieval esoteric Buddhism, where they were associated with reproductive metaphors and therefore fecundity and fortune. Thus ZUN might have made an interesting Taoist-Buddhist syncretic innovation of his own, likely unintentionally.

The interactions between yin and yang are seen to give rise to more refined, divided patterns via a process of transformation and coupling. Yin and yang can transform into each other and be present in different phenomena and objects in different quantities. This makes all kinds of yin-yang combinations possible, which gives rise to the concepts of younger and elder yin and yang, related to the Bagua trigrams. Younger forms of yin and yang possess some of the other, while the elder, mature forms are purer. These are often represented by combinations of two lines, ⚊ unbroken for yang and ⚋ broken for ying. They form the combinations of ⚌ elder yang, ⚍ younger yin, ⚎ younger yang ⚏ elder yin. These four combinations are also sometimes known as the Four Faces of God or Four Images of God in a Westernized context.

These combinations of yin and yang are capable of self-generation, and when they generate a further ”line”, they give rise to the eight Bagua trigrams formed out of three lines of yin and yang. Bagua can be roughly translated as something like ”Eight Revelations”, and considering their connection to I Ching divination, this translation seems quite apt. These eight trigrams are thought to encapsulate the fundamental nature of all matter. These trigrams are massively important to Taoism and wider Chinese culture, and they have correspondences in astrology, medicine, divination, astronomy, geography, anatomy, arts, feng shui geomancy and martial arts.

The eight trigrams and their associated qualities are:

☰ Heaven – Qián – Expansive energy, the sky

☴ Wind – Xùn – Gentle penetration, flexibility.

☵ Water – Kǎn – Danger, rapid rivers, the abyss, the moon.

☶ Mountain – Gèn – Stillness, immovability.

☷ Earth – Kūn – Receptive energy, that which yields.

☳ Thunder – Zhèn – Excitation, revolution, division.

☲ Fire – Lí – Rapid movement, radiance, the sun.

☱ Lake – Duì – Joy, satisfaction, stagnation.

The naming of these trigrams might at first seem unusual from a Western perspective. Some of these overlap with the classical Western elements, but others such as Mountain and Thunder would be considered part of Earth and Air elements in the West. While it’s exceedingly difficult to say where exactly they got their names, as they correlate with phenomena manifest in the material world, it’s entirely possible this is from Taoism’s shamanic origins. They might represent a kind of archetypal ”soul landscape” of China.

These trigrams are traditionally arranged in two different ways: the ”primordial Bagua” or earlier heaven arrangement of Fuxi, and the later heaven arrangement of King Wen. Fuxi was a mythological first emperor of China, who along with his sister-wife Nüwa are attributed with the creation of humanity and giving them many gifts of culture, the earlier heaven arrangement of Bagua included. King Wen of Zhou is an important figure in Chinese history, but for our interests here, he is credited with the creation of the I Ching hexagrams. The later heaven arrangement of the Bagua was revealed to him while he was imprisoned by King Zhou of Shang who was afraid of his growing power.

These two arrangements use the same trigrams, but they are arranged differently and are thought to represent different aspects of reality in the various arts and practices where they are used. The earlier heaven arrangement is arranged using the He Tu mystic square, sometimes called the Yellow River Map because of its association with the myth of Yu the Great who saved China from the Great Flood. In fact, the ”river” of the map is the Milky Way, and it's a map of the constellations. This arrangement is thought to reveal the innate flow of yin and yang, and in Chinese medicine the earlier heaven arrangement refers to conditions that affect one before birth. The Luo Shu mystic square is used to arrange the King Wen later heaven arrangement, and it is thought to demarcate the key patterns of change of yin and yang. By knowing this arrangement, the sage could have control over the four directions, the four elements and space and time. In traditional Chinese medicine, this arrangement refers to conditions which affect one after birth.

As mentioned before, King Wen of Zhou is attributed with creating the I Ching hexagrams by stacking the trigrams of Bagua while in imprisonment. The I Ching, or the Book of Changes, was originally a divination manual from the Western Zhou era of 1000 to 750 BC. It contains a set of 64 hexagrams, and their accompanying text. This text offers an overall description of the hexagram, as well as line by line readings. The line by line readings form little narratives, and some of the hexagram narratives seem to refer or continue each other, creating a web of associations from which people have sought a broader narrative. The text is heavily laden with cultural references, some which have become completely obscure over time. These narratives can be thought of as a kind of a stock of archetypes for events.

These hexagrams are cast using various methods, including but not limited to yarrow stalks and three coins. They are used to construct whether the lines are yin or yang lines, and if they are changing or unchanging. This process of unchanging and changing lines generaly leads to each casting resulting in two hexagrams, the initial one and a change one. This process of change underpins the system, as the first hexagram is thought to describe the current situation and the changing one a potential future. The hexagrams can be interpreted using the narratives (Meaning and Principle), analyzing the component trigrams and their associations (Image and Number) and a kind of numerological-astrological approach known as the Plum Blossom method.

The way I Ching has been interpreted has changed over time. This does not apply to just the methods for divination, but also the understanding of the book itself. The Ten Wings commentary which was added roughly between 500 to 200 BC added a philosophical, cosmological dimension to the work, describing it as a microcosm of the universe and that by taking part in the divination, the sage will cultivate an ability to understand deeper patterns of change. Confucians and Buddhists added their own interpretations, and some later interpretators such as Carl Jung have seen a psychological dimension to it.

There multiple references to the Bagua system trigrams and the I Ching hexagrams derived from them in Touhou. Perhaps the most prominent use of them is Yukari Yakumo's tabard, which has the trigrams for Lake and Earth. Together these form the hexagram ”Ts'ui”. It has the meaning of gathering together to persevere for a goal. This hexagram also signifies great wisdom which is necessary for leadership when directing an assembly together to create overall prosperity for everyone. Whether one thinks of Yukari, this is certainly a hexagram that someone who sees herself as the overseer of Gensokyo would like to display.

Another character whose outfit incorporates the trigrams is Eirin Yagokoro. Her skirt features the trigrams for Heaven, Wind, Fire, Mountain, Earth and Lake. This is similar to the first six gua of the Fuxi arrangement, but with Fire replacing Water. What this sequence is meant to communicate is up to your interpretation. Is it a sequence of changes? Three hexagrams waiting to be stacked?

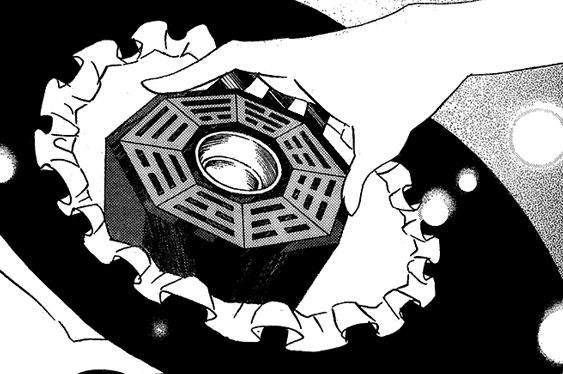

The trigrams of the Bagua are often arranged in an octagonal pattern. Marisa Kirisame’s Mini-Hakkero, the miniature alchemical furnace she uses for spellcasting, is patterned after this arrangement. In fact, the name translates into something like “Mini Eight Trigram Furnace”. Taoist alchemy, both internal and external, uses the Bagua trigrams as conceptual tools, which is likely why she has a tool like this. Another instance of the full octagonal arrangement of the Bagua trigrams making their appearance is Hakurei Reimu’s sigil in Touhou Hisoutensoku. It’s depicted in the primordial Bagua of Fuxi arrangement.

Another reference to the Bagua is how Kanako-sama and Suwako-sama are described as being able to create ”heavenliness” and ”earthliness”. These are a reference to the Bagua trigrams of Heaven and Earth, and their corresponding I Ching hexagrams. The Heaven, Qián, is an active, pure yang force while the Earth, Kūn, is a receptive, pure yin force. These Heaven and Earth have a particular lore in Taoism and wider traditional Chinese beliefs. They are thought to be two of the poles that maintain the three realms of reality. These three realms are the Heaven of the celestial deities, the middle realm of humanity and the chthonic underworld of Earth occupied by ghostly and demonic entities. Rather than being opposed, Heaven and Earth are complementary forces, and themes of the union of the two maintain a very central role in Taoist spirituality.

A considerably more obscure character featuring the trigrams is the ”Moonlight's Anti-Soul” Hourai Girl. The Hourai Girls were a series of characters that ZUN drew between the PC-98 and Windows era Touhou games, which share design features with later Touhou characters. Miss Moonlight's Anti-Soul has the trigram for Water on her chest, fitting her association with the Moon. On her cap she has the trigrams for Wind, Earth and Fire. While not perhaps Taoist per say, the name Hourai comes from Chinese myths about an island of immortals somewhere in the Eastern seas.

A final and slightly tenuous potential reference to Bagua is the name of the fifth Touhou game, Mystic Square. While all sorts of mystic and magic squares are featured in many different cultures and Japan is no exception. An example of such squares from Taoist tradition would be the He Tu and Lo Shu squares, kind of star maps used in rituals.

It’s perhaps a bit surprising that I Ching fortune telling itself is referenced to only indirectly in the Fortune Teller story arc from Forbidden Scrollery. The wooden rods used in Fortune Teller’s method are sometimes used for generating I Ching hexagrams. This method is the same as using the yarrow stalks, but substitutes them for wooden rods.

Before we move on to the five phase changes or wu xing, it's quite worth noting that this system of constructing increasingly elaborate information from binary alterations has some similarities with modern binary code representations of information. In fact, there’s a deeply fascinating connection between I Ching and the development of computer science. The German multitalent Gottfriend Wilhelm Leibniz wrote the earliest Western commentary on I Ching in 1703. He had been working on binary systems before his exposure to I Ching, and noted the binary construction of the hexagrams. Leibniz had also been working a characteristica universalis, an attempt at creating a kind of universal language of logic. Discovering the link between his own mathematical pursuits and I Ching made him realize that binary could serve as a form of communication. This inspired later developments in formal logical systems of Boolean logic and predicate logic, which in turn led to the development of computer logic systems. If you want to follow this line to it’s, the fact that a series of computer games called Touhou Project even exists is because of Leibniz’s exposure to I Ching!

Some have even drawn parallels between the constituent parts of human DNA and the Four Images of God combinations of yin and yang lines. The idea of the universe being patterned around alterations of yin and yang gives rise to a kind of cyclical, spiral-like view of the world. In many ways this is simply factually true – the natural world goes through cycles and growth and decay, and human societies too seem to follow patterns that may not repeat exactly the same seem like elaborations on old themes. It's also remarkable how common spiral structures are in nature, up to them being a rather common galaxy shape.

The Wu Xing cycle

The wu xing, sometimes called Five Elements, Five Phase Changes or Five Agents, are another part of Taoist cosmology. They represent the five phases of change that energy undergoes as it transforms into matter. It can also describe more literal material cycles too. While some consider it similar to Western idea of elements, what divides it from the Western elements is that it's concerned with process and quality rather than substance. ”Tree” is not literal trees, it's rather ”the quality of trees” such as growth and flexibility that is also found in other things.

The wu xing originally referred to the five planets of the Solar system visible to the naked eye (Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars) which along with the Sun (yang) and the Moon (yin) were seen as creating the five forces of life on Earth. From there it became generalized and abstracted into the five phase changes. The phase changes and some of the features and correspondences attributed them are as follows:

The phase changes and some of the features and correspondences attributed them are as follows:

Wood – Growth & Renewal – Jupiter – ☳ Thunder & ☴ Wind – Spring – East.

Fire – Expansion & Assertion – Mars – ☲ Fire – Summer – South.

Earth – Equilibrium & Stability – Saturn – ☶ Mountain & ☷ Earth – Intermediate - Center.

Metal – Harvesting & Gathering – Venus – ☰ Heaven & ☱ Lake – Autumn – West.

Water – Contracting & Retreating – Mercury – ☵ Water – Winter – North.

Once again, the naming of the parts of the Wu Xing cycle are somewhat odd to Western eyes. Some of these are again part of the classical Western elements, yet wood and metal are not, and might initially seem very strange to present as some kind of deeply archetypal qualities. It appears that the components of the cycle are based on the material cycle of metalworking, a revolutionary civilization-enabling technology. This highlights Taoism’s connection to material reality of early Chinese society. The cycle’s most curious feature, metal generating water, is often said to come from condensation. It however might be more specificaly related to items known as moon mirrors, metal objects which were used for gather condensing water at night.

The wu xing can further be divided into yin and yang versions of each other, and each of the Wu Xing have a rather long list of correspondences in the various fields where they are utilized, be it medicine, astrology, geomancy, martial arts... Listing all of them here would make this rather long section much longer. The thing of interest to note here is how heavily reliant Taoist and the broader Chinese thought is on various correspondences, and how Fire and Water phase changes are both associated with singular trigrams. While this might seem just an annoying asymmetry to some, I suspect it has something to do with the role of Fire and Water in Chinese mythology and spirituality. It was after all the clash of gods of fire and water that caused the great flood and forced the reconstruction of the world. Thus there is something very raw, powerful and primordial to Fire and Water.

Before we move on, there is one last important feature of the Wu Xing to be noted. They are thought to exist in a variety of cycles, the most commonly known ones being the inter-promoting and weakening cycles. In the inter-promoting cycle, wood feeds fire, fire produces earth, earth bears metal and water nourishes wood. In the weakening cycle, wood depletes water, water rusts metal, metal impoverishes earth, earth smothers fire and fire burns wood. This underlines the dynamic nature of the system – it really is a process of change. Furthermore, in the various fields where the idea of wu xing is applied, it's thought that deficiencies in certain areas can be supported by bringing in things with qualities from the supporting cycle.

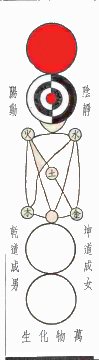

A taijitu chart showing how the world emanates from primordial unity into the yin and yang, the wu xing and then the myriad things.

Stellar Taoism and Chinese astrology

The idea of the wu xing being represented by or emanating from stellar objects highlights the important role astrology used to play in Chinese society. For pre-industrial civilization, knowledge of various cycles of nature and agriculture was crucial for survival. Because the various stars and planets form predictable patterns that correlate with cyclical events in nature, people eventually learned to predict these events. Like all early agricultural civilizations, China developed it’s own form of astrology, and this art was highly esteemed. Knowledge of the ”Will of Heaven”, astrology, was considered a crucial skill for early emperors. Even in later times, only imperial authorities were allowed to make calendars, and making unsanctioned calendars was punishable by death.

China however did not develop in a vacuum, and the dissemination of Buddhism and exposure to different cultures and ideas through Silk Road trade led to dissemination of Indian and Hellenic astrology into China. Buddhism brought with it also the Indian system, and the Chinese merged their system with the Indian one. The Hellenic system got disseminated into China twice, with the first dissemination being of unclear origin and failing to take root. The second dissemination came from the Manicheans and had a more lasting impact. While the native framework rooted in Taoist concepts was the dominant one, all these systems ended up influencing what is Chinese astrology today.

The important components of Chinese astrology are the sun and the moon, the classical planets and the 28 lunar mansions, constellations of the Chinese system. The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar system which divides the year into twelve months based on lunar cycles, with occasionally a 13th month added in to make the calendar be in sync with the seasons. Along this lunar cycle, there are the 24 solar terms which mark the position of the sun in the skies and are related to climate patterns.

The Chinese had two different systems for weeks. One is the older Shang dynasty era ten day week, and the later is the seven day week that is familiar to people of Western origin too. In fact, this seven day week is from dissemination of Hellenic astrology. Much like in the Hellenic system, the days of the week are named after sun, moon and the five classical planets associated with the wu xing. This system got disseminated from China into Japan, where it however was used mainly for Buddhist ritual contexts before 1876.

While the Chinese moved away from the classical naming convention for the days of the week, the Japanese still use the planetary names for weekdays. One can also find traces of the planetary names in many Western names for the days of the week, and the Japanese names for weekdays match these exactly due to the shared origins. In Touhou, this system is referenced in the character of Patchouli Wisdom, called the ”Weekday Girl”. While she is an ostensibly Western mage, she uses the energies of the wu xing and sun and moon for her spells.

The 28 Mansions are a group of constellations derived from the movement of the Moon through the skies. The Chinese system splits the sky into four regions corresponding with the cardinal directions. These regions are assigned the Four Symbols, guardian deities of the directions which are also representations of various attributes given to the directions and their corresponding seasons. Each of the four regions has seven mansions, making for 28 in total.

The Chinese zodiac, or more accurately the Twelve Earthly Branches, is a distinct and popular element of Chinese astrology, used in the naming of years. The Early Branches are a symbolic system of twelve animals that makes a twelve year cycle. In astrology, each of these animal symbols is thought to embody certain characteristics which are imparted to people born on that year. This system is truly ancient, and it’s origins are somewhat murky. It has been suggested that the division of twelve comes from the rougly twelve year orbital period of planet Jupiter, the third brightest natural object in night skies. Besides the calendrical and astrological functions, the system was used for directions and prefered by Chinese astronomers and sailors. This is similar to using the division of a 12 hour clock for directions.

Another distinct feature of Chinese astrology are the Ten Heavenly Stems. They were used for the names of the Shang ten day week. As the Chinese no longer use the ten day week or the Heavenly Stems for names of the days, this system finds use mostly in astrology and related arts and certain types of lists and naming conventions in China. Historicaly the Heavenly Stems might have been ten asterisms marking the progression of the moon through the skies. They might also be related to the Chinese legend about the ten suns and the archer Houyi. After the Shang dynasty collapsed, the system changed and became associated with the wu xing and yin and yang. In the astrological system, the Heavenly Stems are essentially two sets of wu xing, one of yang qualities and one of yin qualities. So for example 甲jiǎ is Yang Wood, like a strong and robust tree, and 乙yǐ is Yin Wood, softer and more pliable, like grasses and leaves.

Combining the Ten Heavenly Stems and the Twelve Earthly Branches leads to the third distinct, perhaps the most defining feature of Chinese astrology. That is the sexagenary cycle, a cycle of sixty years. In this system, a Heavenly Stem is combined with an Earthly Branch. People with even surface level knowledge of Chinese astrology have probably heard of things like ”Year of the Metal Dragon” or ”Year of the Fire Horse”, and it’s exactly from these combinations that these naming conventions come from. The English translations tend to lose some nuance, as the Heavenly Stems are commonly translated with the base wu xing instead of their full yin or yang flavored qualities. These two systems are combined via a process of least common multiple, the smallest number divisible by two different numbers, in this case ten and twelve. This number is 60, leading to the sixty year cycle.

The sexagenary cycle however isn’t restricted to only years, and it has a kind of fractal nature. There is a sexagenary cycle of hours, days and months within the system too. In fact, the system was in ancient times used first for counting days. The Heavenly Stems are from the ten day week, after all. Using the cycle for years was a later innovation. Earliest example of using this cycle for years is from around 168 BC, and it became more widespread for timekeeping towards the start of the common era. In Japan, the sexagenary cycle was taken into use in the year 604. The Japanese had been aware of the system before this, but waited untill the first year of a sexagenary cycle to take it into use.

In the sexagenary system, the twelve months of the year are associated with the Earthly Branches. This is a newer practice than using them for a twelve year cycle, dating back the 2nd century BC. The Earthly Branches were coordinated with the orientations of the Big Dipper in the skies. These days, these ”Branch Months” are not used for usual month names and are of astrological function. To make full use of the astrological function, these are combined with Heavenly Stems, this time in a cycle of five years.

The traditional Chinese hours are two Western hours, and thus the day has 12 hours instead of 24. These twelve hours are also associated with the Earthly Branches. Much like the months for five-year cycles, the combination of Stems and Branches creates a cycle of 60 Chinese hours, or five days.

As one can see, the system is rather symmetrical and beautiful, with the 60 hour cycle making for half of a ten day week, making kind of yin and yang halves of the week. Six ten day weeks makes a sexagenary day cycle, and such cycle covers two of the twelve months of the year. Thus each year has six sixty day cycles. The months have their own sexagenary cycle of sixty months, or five years. The whole sexagenary year cycle is then five sexagenary month cycles. Of course, in reality the year is not 360 days, and the perfect harmony of the system falls apart, leaves a gap. Whereas in the West the calendars have leap days, the Chinese have opted for a system whole extra 13th month appears every 2-3 years. These months are given the same name as the preceding month.

In Touhou, this sexagenary cycle is referenced to in Phantasmagoria of Flower View and works referencing the Flover View incident. In Flover View it’s stated that a similar incident took place in ”sixty years before”, or 1945, the end of Second World War. Season Dream Vision goes deeper into the idea of the cycle. It’s described as being the time it takes for natural processes to run their course and revert back to start, and thus something like the Flower View incident is implied to repeat every sixty years. The origin of the cycle is also explained as being derived from the three lights (sun, moon, stars), four seasons and the wu xing cycle. It’s quite likely that this is some kind of real life justification for the construction of the sexagenary cycle.

In Touhou, Gensokyo uses a youkai calendar that also runs in sixty year cycles. While it’s constructed differently, the idea of a sixty year cycle most likely comes from Chinese astrology, especially as it contains the wu xing. The youkai calendar doesn’t use Stems and Branches, but rather it uses three components: Light, Season and Agent. The Light refers to the Three Lights, or Sun, Moon and Stars, a concept of apparently Japanese origin, possibly influenced by Chinese thought, about how these objects endow different qualities into the world. The Sun has an overwhelming, assertive presence, the Moon is cooperative and indecisive, and the Stars are erratic and uncooperative. Four seasons are self-explanatory and the Agent is simply one of the wu xing.

While the Chinese sexagenary uses the least common multiple, the youkai calendar runs the three cycles simply in parallel, which lines up into a 60 year cycle. The two systems have some mathematical commonalities, as Multiplying Season by Light results in 12, which then multiplied by Agent turns into 60. The youkai calendar curiously lacks hours or days, as it’s said that due to the youkai’s long lifespan, they consider a month their ”day”, the lowest amount of time worth measuring.

The youkai calendar is said to accurately predict various natural phenomena, including things like earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The given reasoning for this is that it’s constructed out of natural cycles. This cycle is also apparently related to the creation of the Great Hakurei Barrier, as it’s sixty year cycle lines up perfectly with it’s given creation year of 1885. The cycle also includes some kind of element of mass deaths occuring towards the end of the cycle. In Phantasmagoria of Flover View, it’s said that every 60 years there is a great surge in the amount of phantoms traveling to the afterlife. This causes the flover view incident to repeat in 60 year cycles. Flover View’s release year of 2005 was close to one of the worst natural disasters ever recorded, the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. The previous cycle would have ended in 1945, towards the end of the Second World War. The 1885 cycle would have been relatively close to the 1883 Krakatoa eruption, and the reforms of Meiji era that aimed to curb ”superstitions” would have likely triggered a mass dying – or exodus – of youkai and other supernatural creatures.

It should be noted that the sixty year cycle of the youkai calendar, driven by some kind of cycle of natural energies, is offset from the Chinese sexagenary cycle by 22 years, so it’s not the same cycle. It’s unclear why this was chosen. It might be to create a 60 year gap between the events of Flover View and end of Second World War. It’s also possible that there are some kind of theories regarding the predictive power, construction and the possibility of a more ”real” sexagenary cycle floating around in Japanese occult circles. The two cycles seem to have one thing in common though, and that is the time around Chinese lunisolar new year being the startpoint of a year. Flover View and it’s incident take place around spring higan, a Japanese Buddhist holiday on spring equinox, which close to the lunisolar new year.

The idea of a sixty year cycle reflecting some kind of broader cycle of nature might very well be rooted in real ideas about the Chinese sexagenary cycle. Astrology has always had aspects to it that went beyond predicting repeating seasons and weather cycles. Chinese astrology is no exception, as the time and date of birth was thought to influence the type of person. Particular characteristics of Chinese astrology in this regard is the influence of the 12 year zodiac cycle, and the idea that the stars and planets determine person’s internal wu xing and their balance. So for example, it would be possible for someone to have a very low amount of Wood in their chart. This would mean that the Fire wu xing would not have ”fuel”, which would lead to lethargy and the situation would be worsened if there was a strong Metal presence which the Fire would need to ”melt” for a balanced cycle. Such deficiencies or excesses would not however doom a person, as it was thought one could acquire more of particular types of wu xing from their environment. Thus a Wood deficient person would be recommended to spend more time in nature and to get plenty of houseplants.

Chinese astrology of course also found applications in fortune telling, as the idea of celestial objects patterning life energies on Earth was believed to forecast events beyond the start and end of harvest season. There exist so called Three Styles of Chinese divination based on astrology, and they are the Da Liu Ren, Tai Yi Shen Shu and Qimen Dunjia. The last of these, Qimen Dunjia, is referenced to in Touhou. Originally, this system was used mainly for strategy in war, and the system is regarded as being rather complex. In essence, it’s a system for determining the right time and right place for planned actions. In Wild and Horned Hermit, where Tenshi uses her knowledge of the Qimen Dunjia to locate Reimu when she disappeared into Hell.

The Taoist Pantheon

Chinese astrology is directly linked into the Taoist pantheon, as many of the deities found in it are personifications of the various planets, stars and constellations. Other deities are personifications of primordial forces, venerated ancestors or more complex, ambiguous figures. Some deities are ascended beings who were born as humans or other entities and rose to became celestials. Some forms of Taoism also absorbed some Buddhist deities, perhaps most notably the popular Chinese version of Avalokiteshvara, Guan Yin, known as Kannon in Japan. While Taoism never became a mass religion in Japan, some Taoist deities reached Japan, and became part of other religious and mythological contexts there.

The most venerable of the Taoist deities are the Three Pure Ones. They are considered the most primordial manifestations of the Tao, the primordial, impersonal, undivided wuji splitting into three deities that then shape the universe. They are considered the sources of all existence and have control over time, and sometimes each of the three are seen as representing the past, the present and the future. In the process of creating the world, the three create the universe, divide it’s energies and set natural laws and then pass on knowledge of the universe to humanity. These deities are also seen as representing the energy of the Heaven, the energy of the human world and the energy of the Earth.

The division of the cosmos into Heaven, the Humanity and the Earth is an important, recurring theme in Taoism. Heaven represent yang principles, and is procreative, putting things into motion and shaping them. This was seen in how various celestial phenomena were thought to rule the events on Earth. Many Taoist deities are therefore personifications of various stars and planets. Heaven was seen to be most manifest in the northern night skies, full of stars. Earth was seen to be with yin qualities, receptive and nurturing, acted upon and shaped by Heaven. This yin world is however also imbuded with cthonic qualities, being a place of ghosts and demons, a kind of inframundane side to what humans commonly perceive to be Earth.

The world of humanity sits in the middle, and humans are beings of both yin and yang qualities. The role of humanity is seen to be a harmonizing force between these two, both on a collective and an individual level. This idea is slighty referenced in Touhou, with the qualities of the two Suwa kami representing Heaven and Earth, and Sanae as an implicity Humanity between the two. More outright, it’s referenced in Tenshi’s powers and Sword of Hisou.

The broad idea of celestial realms being inhabited not only by deities but also be ascended beings is present in Touhou. Hinanawi Tenshi is a delinquent celestial who became bored with life in the heaven and descended into Gensokyo to fight for fun. She is returned into the Heavens, but gets banished for eating a Peach of Immortality before a banquent. She was a member of a clan known as Hinanawi, who served the Nawi clan. When the Nawi became enshrined as divine spirits, the Hinanawi too were raised to the celestial realms. They were however seen as lesser celestials due to them ascending through association with the Nawi, and not training. In Touhou, the heaven is ”full” and closed to outsiders, making it impossible for any more people to ascend there. These kind of ideas can be found in some Chinese folk mythologies.

If the Three Pure Ones are revered as the creators of the world, the Jade Emperor is revered as it’s ruler. In the legends, Yuanshi Tianzun, the most primordial of the Three Pure Ones, delegated the rulership of the universe to the Jade Emperor. This can perhaps be seen mirroring the idea that the Emperor of China ruled China as a representative of the forces of Heaven, Humanity and Earth, and that ultimately this right came from extremely primordial celestial forces. Much like the Emperor of China would rule over a complex bureacracy, so did the Jade Emperor rule over a celestial bureacracy. In some Chinese mythology, he is equated with Yu the Great, who brought order to the world after is faced a catastrophic flood. In Chinese Buddhism, he is associated with Indra, a supreme celestial deity of Indian origin. The Jade Emperor and certain legends associated with him spread over to Japan, but his influence on Japanese religion as a whole was limited.

The Jade Emperor was historicaly often seen to be the same as Shangdi, an earlier supreme deity of the ancient Shang dynasty. The Shang ruled from roughly 1600 to 1046 BC, and their reign saw the development of many formative features of Chinese culture, such as the earliest Chinese script. Shangdi was considered so distant and abstract that he could be reched only through various intermediaries. He was not completely without representation though, and he was associated with the Big Dipper and the Pole Star. Shangdi himself was associated with the Pole Star, and the Big Dipper was seen to be his throne.

This association with a supreme deity endowed the Big Dipper with

great importance in Taoism that went beyond it just being the throne of

Shangdi. The Big Dipper's role in Taoism can be roughly split into four

categories:

1) The Big Dipper indicates the proper direction for performing rituals

or meditation through the movement of its ”handle” through the year. In

the earliest forms of the Chinese calendrical system, the Big Dipper was

the ”timekeeper” whose rotation determined the seasons.

2) The Big Dipper is believed to open the way to Heaven via it's seventh

star, Tianguan, Heavenly Pass, in rituals and meditation

3) The Big Dipper is a recipient of invocations of forgiveness for one's

sins and to have one's name erased from the ”registers of death”,

siji.

4) The Big Dipper is believed to have strong exorcistic powers due to it

being a divinity of the North, but also the underworld. The direction of

the Big Dipper orientation determines from which direction the thunder

is summoned in the exorcistic Thunder Rites.

In certain Taoist beliefs the Big Dipper is also associated with the creation of the universe, as well as ensouling humans. Some find traces of Big Dipper in the human bodies, equating the seven stars with things like the seven holes of the human head.

As one can imagine from this multitude of roles, the Big Dipper was considered to be of utmost importance and vast power. Thus many practices for invoking its might came to be developed. An example of these are the Bugang rituals, a form of Taoist ritual dance. In one version of these rituals, the practitioner paces through a pattern made in the likeness of the Big Dipper. Many great benefits are thought to arise from this practice: the ability to avoid blame, weapons and death itself and command over vast spiritual powers and the ability to reach out to the gods.

A particular feature of Taoism is how the otherworldly is ruled in a bureacracy that is strikingly similar to bureacracy of the Chinese Empire. This hierarcy covers both the celestial realms and the underworld. While Jade Emperor is the obvious chief of the heavenly bureaucracy, the bureacracy of the underworld is led by Dongye Dadi, the grandson of Jade Emperor. He holds the Book of Life that holds the death dates for all of humans. He is the ruler of the Judges of Hell, who judge dead humans for their merits and decide their fates. The Chinese belief in Dongye Dadi and the Judges of Hell became syncretized with Buddhism, and as mentioned in the Buddhism section, these beliefs also spread into Japan. Dongye Dadi also made his way to Japan also on his own, becoming known as Taishan Fukun and becoming revered in Onmyodo.

Religious Taoism also incorporates reverence towards a deified version of Laozi. In such form, he is called the Heavenly Lord of the Tao and it’s Virtue, and is considered a deity predating Heaven and Earth who chose to manifest as a human to teach humanity. It’s said that Laozi’s mother was a princess who had a dream of a god entering her. She became pregnant and carried Laozi in her for whole 81 years, untill he was finally born through her armpit, his mother dying in the process. Thus Laozi would have appeared in the human world already as an old man with perfected wisdom and knowledge.

An interesting part of the Taoist theology is the idea of internal deities, also known as body gods. As the name suggests, they are deities that reside within the human body. These internal deities replaced older ideas of organs as impersonal storehouses of qi. This development can be seen as an attempt to illustrate the microcosmic-macrocosmic principles of Taoism. Just as the world was seen as a place where various deities acted on, so was the human body one where various deities acted on. These deities too were seen to follow a bureaucracy of their own. Practices surrounding these deities emerged, including ones aimed at clearing out excess emotions and desires from organs to make space for the internal deities. There are ideas in Japan that are similar, and it’s likely the idea of Taoist internal deities became disseminated into Japan over time.

Xiwang Mu is a Taoist deity with possible connections to Touhou through the character of Yakumo Yukari. This ancient deity is considered a mother goddess and an ambiguous deity of life, death and immortality. She holds court at the mythological Mount Kunlun, residing at a palace that serves as a meeting place for deities and a cosmic pillar through which humans can communicate with deities. It’s also said that her gardens held orchards for Peaches of Immortality. She was initially seen as a fierce goddess of death, but eventually her image changed. A mythology developed around her where she was seen as a demonic being who had ascended her own nature and became a celestial being by doing so. She’s tasked with guarding the herb of immortality.

Was Yukari-sama the first ”troublesome one” that ”moved on her own”?

Xiwang Mu is associated strongly with the planet Venus, and Yukari is associated with Venus through her second theme song, Evening Star, Night Falls. Evening Star is the name for Venus’ phase where it’s visible in the evening. The two phases of Venus inspired mythologies about divinities associated with Venus who would go through some kind of transformation process. Xiwang Mu’s association with Venus might reflect this mythological arc, as does Yukari’s implied origins as an ordinary human being. This change in character and ambiguous status as a deity of life and death gives Xiwang Mu a kind of liminal nature, much like Yukari’s abilities reflect her nature as a liminal being. In fact, in her first appearance, Yukari manipulated the boundaries between life and death, allowing for a state of not alive or dead. This idea of immortality being a state beyond or between life and death can be found in Taoism. Xiwang Mu is depicted as having two raven servants, as is Yukari. Xiwang Mu’s status as a queen of her realm can be seen as being analogous with Yukari’s role of sage of Gensokyo. Yukari’s tabard with hexagrams situates her within the influence of Taoism, and her otherwise Western appearance might be a kind of pun on Xiwang Mu being the Queen Mother of West. Lastly, purple is seen as a color associated with spiritual power and authority in Taoism.

One Taoist deity that is directly referenced in Touhou is Chang’e, the Moon goddess. Interestingly enough, Chang’e is one of the ascendant deities. There are many variations of her tale, but she was the wife to legendary archer Houyi who saved the world from destruction by shooting nine out of the ten suns when they one day rose up all at once. There are two versions of the story on how she became a moon goddess. Both have to do with an elixir of immortality that Houyi possessed. In one version, Houyi left Chang’e to guard the elixir because he did not want to become an immortal without his wife. However, Houyi’s apperentic Fengmen breaks into his house while Houyi is on his quest to shoot down the suns, intent on stealing the elixir. In order to prevent this from happening, Chang’e consumes all of the elixir. In an older version, Chang’e is apparently less happily married and steals the elixir herself.

Qi, shen and jing, the life energies

As has been established, Taoism views reality as a process of patterning of energy. For some Taoism is all about understanding this flow and patterning and becoming part of it in an effortless manner. For others, it’s more about intervening in this flow, whether by human efforts or by petitioning deities. But what exactly is this energy that gets patterned in this increasingly complex process? The Taoists would call it qi. It literally means ”vapor”, ”air” or ”breath”. Broadly speaking, qi is seen as the fundamental thing that makes up the universe and all the things in it. In the end, all the things eventually dissipate back into qi again. It's thought that as qi becomes patterned by the processes of patterning and change, its fractions acquire different characteristics such a coarseness or heaviness. The most ethereal fraction of qi was thought to be the qi that gave life to living things.

It's indeed this qi of life that is perhaps most well known, and within Taoist thought, this qi is divided into various forms of qi. There is the primordial qi, acquired from parents, the qi of air, the qi of food... The human body in general is seen as having both corporeal and incorporeal aspects, organs and parts, elixir fields, inner substances, animating forces and energy channels.

Because qi, both as qi of air and the life-giving version, was so strongly associated with air, it likely explains why something analogous to Western element of Air is absent from the bagua and Wu Xing. Air was simply conceptualized to be something different, perhaps even more fundamental than what the bagua and Wu Xing represent.

Beyond qi there also is shen, which is a spiritual force that is responsible for power, agency and capacity to connect with the spiritual aspects of reality. There is also the jing, which is a kind of personal life force, some of it acquired from parents at birth, some of it acquired later in life via metabolizing qi. Jing is continuously consumed by everyday life, and can be consumed in excess by things like stress, illness, substance abuse and excessive sexuality.

Energy Medicine and Immortality Elixirs

Taoism developed a very elaborate ideas of energetic zones and channels within the human body, which acts as a conduit for various life energies. It’s also seen that the ways these different energies manifest in humans correspond with the Wu Xing phases, and that various external conditions such as environment and food impact these internal energies. These ideas formed the basis for Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Chinese Traditional Medicine relies on the idea of working with these life energies. While some of the ingredients used in these treatments are conventionally pharmacologicaly active, some have no known pharmacological activity correlating with expected effects. The idea is rather to supplement the body energies it is perceived to be lacking, or to suppress energies that are present in excess.

Some forms of Chinese Traditional Medicine, such as acupuncture and massage, rely on manipulation of various energy channels and centers directly in the human body. Here the idea is to redirect energy from one place to another in order to facilitate healing. There’s also even more occult forms where the practitioner attempts to directly project energy in to the recipient.

A culmination of these ideas surrounding life energies and preservation is of course the idea of preserving the life energies and therefore life itself forever. The pursuit of immortality led to the creation of Taoist alchemy. While the obsession of Western alchemy was the creation of gold, Taoist alchemy was involved in the pursuit of creating the elixir of immortality. As with the Western form of alchemy, the pursuit eventually took on a more spiritual, transcendental character while never entirely abandoning the material work either.

For a long time, the pursuit of the elixir of immortality was one of outer alchemy, or waidan. These were mixtures of metallic or herbal medicines, containing things such as cinnabar (a form of mercury), mercury, sulfur, lead and gold. The end results of these operations were more often than not toxic in conventional medical sense, and it’s been thought that the erratic behaviors of certain emperors who ingested them could have been caused by heavy metal poisoning. The negative effects of waidan practices are referenced in Touhou, where Toyosatomimi no Miko resorts to more arcane means of achieving immortality because her body has been ruined by cinnabar consumption.

The Chinese of old were not unaware of the toxic effects, and it’s unclear why the culture of consuming such concoctions persisted. Several theories have been presented as to why these alchemical practices persisted. One theory is that the elixirs would lead to an initial perceived increase in well-being and virility. Other theories are related to the elixirs creating conditions where bodies became extremely resistant to decay. An undecaying corpse could have be been seen as proof of immortality in a more spiritual sense. Some claim that the consumption of elixirs was in fact a kind of ritualistic act of self-sacrifice.

There developed a myth that the true elixir of immortality could be found in the island of Penglai, known in Japanese as Hourai. There has been speculation that legends of Penglai were shaped by early Chinese visitors to Japan, but the many fantastic characteristics given to Penglai are not found in Japan as we know it.

The Penglai/Hourai mythology as well as the elixir of immortality as a broader idea is of course referenced to in Touhou. The character Houraisan Kaguya has consumed such an elixir, created by Yagokoro Eirin. For this, Kaguya was exiled from the Moon to the Earth. Fujiwara no Mokou also drunk this elixir, which she took from soldiers trying to destroy the elixir on the orders of the Emperor of Japan.

In Touhou, the elixir of immortality’s actual function is as a tool of influence by the Lunarians. They used promises of the elixir to manipulate various groups of humans in order the create chaos and conflict, stirring the development of society. For a Lunarian to drink the elixir, it would signify they lack faith in the perfectly unchanging conditions of the Moon. To do so would invite the impurity they dread, and thus Kaguya was exiled for drinking the elixir.

It should be noted that Zun has also referenced the Hourai mythology elsewhere, including things like Alice Margatroid’s Hourai Doll and the ”Hourai Girls” he drew in between the PC-98 and Windows eras of Touhou. This fascination might come from Lafcadio Hearn’s retelling of Hourai as a place based on wintery Japan, as Zun’s work contains references to Hearn. Hearn’s depictions were likely influenced by later Japanese re-interpretations of the Hourai myth that gave it a considerably less paradisiacal interpretation, painting it as a cold island inhabited by fairy-like creatures.

Inner Alchemy

The other side of the Chinese alchemical coin is the art of inner alchemy, or neidan. Since humans are seen to be manifestations of an energetic reality, the idea that these energies present in humans could be cultivated, purified and alchemized through internal methods. These methods include meditation, visualization, breathing and posture excercises. It's thought that through these practices it's possible to improve health, extend life and even cultivate supernatural talents. These abilities included things like being able to clearly perceive the spirit world, and being able to manipulate various energies for feats such as levitation or setting things on fire. The ultimate feat however was the attainment of immortality.

Internal alchemy’s pursuit of immortality took on a more spiritual character. In Taoism, the human is thought to have several of what in Western context would be called ”souls”. Just like yin and yang are present in everything, so they are present in these souls, divided into three hun and seven po. Hun is the spiritual yang soul, and po is the corporeal soul. Aging is seen as a process where the hun weakens, and death as the ultimate separation of the hun and po. Thus if one could prevent the weakening of the yang and the separation of the souls, one would become immortal. Ultimately in some sects the aim came to be seen as the creation of a kind of ”spirit fetus” inside oneself, an unification of the many different component souls that would weave together a form of consciousness capable of surviving physical death. As abstaining from sex was part of these practices, a logic of spending one’s life energies to perpetuate onself and not to create offspring perhaps underpinned this form of cultivation. The idea of hun and po also reached Japan, where they existed alongside native and Buddhist ideas regarding the human soul, death and afterlife. In Japan, they became known as kon and haku, often refered together as konpaku the very same ”Konpaku” as is in Youmu’s surname.

This tradition of inner alchemy persist to this day, and over time it merged with Taoist martial arts, turning into the internal martial arts, neijia. These internal arts went on to influence also later developments such as modern qigong. The Taoist or Taoism-inspired internal arts that exist today range widely in aims and qualities, from the accessible to extremely demanding and esoteric. Ideas derived from Taoist thought regarding the life energies and qi have also made their way into the ”hard”, external arts, or martial arts as they are more widely known.

The archetype of a martial artist who has supernatural talents, popular both in China and Japan, comes from these ideas regarding self-cultivation and their application to martial arts. At the extreme end these supernatural talents suited for combat include projecting energy in a harmful manner. Even today there are claims of masters of the arts being able to push people or set objects on fire with qi. This idea of projecting energy out of the body likely had a very broad influence on fictional depictions of magic, perhaps even including the energy projectiles of Touhou.

In Touhou, the character of Hong Meiling is a rather archetypal neijia fighter who can ”manipulate chi”. She’s also described by Akyuu as practicing Tai Chi in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense. Tai Chi is an example of a Taoist internal art that enjoys some global popularity these days. The slow, relaxed, deliberate movements of the form and supporting practices are thought to make the body more conductive to a healthy flow of chi.

Another character that is portrayed with features associated with cultivators, practitioners of inner alchemy, is the character of Ibaraki Kasen. While her religious affiliation is ambiguous at best and she is an oni, a supernatural being, she is described with powers and practices associated also with Taoist mystics. She’s called a hermit, a translation of the Chinese xian, a term which more fittingly would mean ”immortal” or ”transcendent” or ”ascendent”. Not all xian were hermits, though social seclusion was thought to be conductive to practice. Taoism has a long history of practitioners withdrawing from society to nature, and later to Taoist monasteries. Laozi himself is often seen as having been a hermit. This way, one would not be dispersing their energies all over the place and there would be less distractions for practice.

Kasen’s process of cutting of her arm, sealing her most evil urges there, but eventually being forced to come to terms with her past and re-integrate herself could be read as a kind of process of internal alchemy, particularly as a modern interpretation of a kind of shadow integration process. Her demonstrated power of guiding and transfiguring a youkai sees her act as a mentor, much like seasoned real-life cultivators often end up guiding others. This can even be seen a manifestation of the spirit guide archetype, a role that sometimes the mythical xian and real-life cultivators also take up. A last detail when it comes to Kasen is that there are Chinese legends of advanced cultivators developing non-human physiology, including horn-like bone nubs on their foreheads. This might have influenced her design.

The many types of Immortals

Ibaraki Kasen is not the only character described as a hermit or immortal, and other characters described as such include Kaku Seiga, Mononobe no Futo and Toyosatomimi no Miko. Their immortality however does not come from typical neidan cultivation or a succesful waidan operation, but rather more arcane means. This reflects Taoist ideas that there were multiple, some more perfect than other, paths towards immortality or transcendence.

Traditionally, immortals were grouped into celestial, earthbound and corpse-liberated. The most perfected of immortals would ascend to heavenly realms, sometimes described going there in very grandiose ways, such as being taken in there by dragons. They would essentially become deity-like beings. Earthbound immortals achived their immortality through cultivation, but were less perfect than the celestial ones, thus remaining on Earth.

The Taoist clique of Toyosatomimi no Miko are part of the group of corpse-liberated immortals. Essentially these immortals would trick death with magic, substituting their corpse for an object that was buried instead of them. This object in Chinese is called shijie, and in Japanese shikaisen. The shikaisen objects of these characters are known: for Seiga, it was a rod of bamboo, for Futo, a porcelain plate and for Miko, the sword she carries around. Soga no Tojiko is a failed corpse-liberated immortal, as Futo betrayed her and tricked her into using an unifred clay jar as a shikaisen object. This jar dissolved, but Tojiko’s spirit survived as a wrathful ghost.

Beyond the degree of ”perfection” of immortality, there were also seen to be many different means to achieving it, not limited to ones described here. Some immortals described in literature and Taoist canon were rather unconventional figures, at times detached from broader society, building on the hermit tradition. Some immortals were also described as unfortunate figures, perhaps unexpected of their transcendent status. An example of this is the tale of Qin’e, on which is story for Kaku Seiga is based on.

Qin’e’s tale is from from Pu Songlin’s collection of stories known as Liaozhai, ”Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio”. Written during the Qing dynasty, with work starting in late 1600s and ending in early 1700s, it’s collection of around 500 tales of the supernatural. While some of the tales have qualities reminescent of Western horror, they are not intended to be scary, but rather to blur the lines between ”natural” and ”supernatural” worlds.

In the story, Qin’e is a teenage girl whose father is a Taoist practitioner. Qin’e secretly reads his father’s texts and starts to admire He Xiangu, one of the Eight Immortals. When Qin’e’s father leaves for the mountains to become an immortal, Qin’e declares that she will never marry, perhaps mirroring He Xiangu’s legend. Unfortunately for her, a young man called Huo Huan becomes obsessed with her. The two end up eventually married after several unsavory turns of events, which include Huan invading Qin’e’s home using a tiny magical spade that can cut through solid rock. The unhappily married Qin’e eventually has a child with Huan, but she is not interested in raising him, trusting to son to a nurse and declaring that the time these two have together will end soon. Qin’e seemingly dies. Huan however ends up finding a house in a cave mountain, and Qin’e in there. It’s revaled that Qin’e used Taoist arts and buried a bamboo rod in her stead. Qin’e eventually ends up going back with Huan and has another child with him.

After becoming familiar with the story of Qin'e, it's easy to understand why Seiga would choose to become a ”wicked hermit”.

While there are differences between these two stories, and ZUN doesn’t include the most unsavory aspects of the tale into Seiga’s background story, it’s a relatively straightforward adaptation. Seiga’s name is in fact a Japanese reading of Qin’e’s personal name with her husband’s surname. The difference seems to be that in the world of Touhou, Qin’e escaped the unhappy marriage and fled to Japan.

The He Xiangu that Qin’e admired is one of the Eight Immortals, legendary xian who are revered in Taoism and popular figures in more secular Chinese culture. They are essentially seen to be deities who ascended their human natures through various means. These eight too are quite the varied bunch. Some of them are said to have achieved their immortality through more ”conventional” means. He Xiangu is said to have reached her status through eating mica powder and staying virgin, while Zhang Guolao became immortal through mastering the occult arts. Some of the legends are a bit more unconventional. Lan Caihe, a wandering ambiguously-gendered wandering street entertainer has several legends about how they became an immortal. In one of them, drunken Lan Caihe throws down their possessions to the ground and is taken to the heavens by a cloud. The legend of Li Tieguai tells how his spirit went to the celestial realms to meet with other immortals. Returning to Earth, he is dismayed to find his body burned, and is forced to enter the fresh corpse of a decrepit beggar, and becoming fully fledged immortal in such a form.

The Eigh Immortals are revered, but they are also very human, having character flaws, and are generally depicted as being fond of fun and drinking. Their paths and personalities are also very different from each other. In this sense, the message of Taoism seems to be that there are multiple ways to even the most highest forms of achievement.

Magic in Taoism

Taoism’s elaborate ideas about the flows and patterning of energies and how they could be controlled and shaped led to an elaboration of early shamanic and folk magic practices, and what followed was the birth of Taoist magic. ”Magic” is of course a highly ambiguous term to begin with, and one could argue that in Western context ”magic” was simply spiritual practices not aproved by Christianity. The Taoist internal arts already veer into what many would consider magical or at least supernatural. As many of the practices described in this section were and are practiced by Taoist clergy, they could just as well be seen as forms of religious practice. Many of these practices and ideas have however also escaped the confines of formal religious Taoism. Furthermore, these practices share notable similarities with Western ideas of ”magic”, hence the idea of Taoist magic is aproriate.

Taoist thought has a fractal-like nature, and the world is seen to be full of correspondences. This makes the Taoist worldview remarkably similar to the Western ideas of microcosm-macrocosm. This idea is essentially that there are aspects in humans that correspond to the external world and vice verse. Hence it becomes possible to influence humans through indirect external means, and for humans to influence the external world through indirect means. This microcosmic-macrocosmic idea forms the basis of not only the idea of energetic correspondences in Traditional Chinese Medicine, but also Taoist forms of symphatetic magic.

Symphatetic magic is the idea that things can be influenced indirectly by using some kind of perceived ”connection” or ”similarity” between two objects. An example from the Taoist magical tradition related to this would be crafting a talisman that is thought to carry specific energies in order to help someone to recover from an illness.

This crafting of talismans known as fulu talismans is an important part of the Taoist magical tradition. They are alkso an example of the Taoist magical tradition that influenced Japanese culture and Touhou. These talismans have magical symbols and incantations written in a script that is reminescent of Chinese but more often than not has no sematic meaning. The characters written distort, elongate and add non-character symbols to Chinese script. Sometimes they can be completely abstract, and sometimes they can include things such as constellations. The talismans are purposefully indecipherable. This tradition developed over time, perhaps as a measure to stop just any literate person (as rare as they were) from copying talismans. It has also been presented that the indecipherability and the scrip sitting at the borders of recognizability contributes the supernaturality of the talismans. The very act of calligraphy, once a skill of elite few, was thought to be spiritually charged on it’s own, and the high regard for this art contributed to Chinese resistance to moving to a different form of script.

The fulu talismans are created and used for a very wide range of purposes, including protection, healing and exorcism. These talismans made their way to Japan influenced the ofuda found in Japanese Shinto and Buddhism. It’s from the fulu where the paper strips that Reimu brandishes as exorcism tools come from. The various card-shaped projectiles are also likely influenced by fulu via ofuda. It’s also possible that the fulu influenced the very idea of ”spellcards” in Touhou. Since some fulu are written as instructions for spirit, perhaps akin to programming, it’s only a slight leap of logic if even that to conceptualize magical tools that would generate patterned energy bursts once invoked.

The talismanic practices of Taoism have a very interesting connection to the idea of human being a microcosm of the larger macrocosm. The process of making talismans has been conceptualized as a way for practitioners to communicate with the various spirits that inhabit one’s body. However, because the individual human is a microcosm, these spirits are also the spirits of the broader macrocosm. This act not only allows for magical attempts at controlling external forces, it in a way makes the microcosm-macrocosm visible. The art of making talismans is also an art of extracting the practitioner’s own image of the universe from inside onself. This image in turn is of course shaped by the Taoist tradition.

Taoist magical practices also include various incantations and hand gestures, similar to Buddhist mantras and mudras. A popular one in Japan which is of Taoist origin but crossed borders of religions very early on is the Kuji-In mantra and the associated Kuji-Kiri, or Nine Cuts, gestures. This nine syllable incantation was originally chanted before entering sacred mountains for protection. It’s basicaly a petition for ”all the soldiers” to assemble for the invoker, understood to be a reference to protective spirits. The nine syllables are all associated with particular hand gestures. Sometimes the incantation is used in whole, sometimes particular syllables and gestures are used. As the Kuji-In practice became part of Buddhism, certain forms of Shinto and various syncretic forms of practice, the particular syllables and gestures acquired further meanings. They became associated with particular concepts or supernatural powers and various buddhas, bodhisattvas and kami.

The associated Kuji-Kiri practice involves making nine cuts or strokes, alternating between vertical and horizontal ones. These form a grid. In this grid, a kanji representing something that the practitioner wishes to ”cut” is drawn, and the process is often closed with an extra tenth syllable. This ”cutting” can be done with one’s fingers against air, but also with a sword, or as strokes on a paper. The purpose of this act is to bring the target that is written within this grid under one’s control, or to destroy it. This practice has been used as an exorcism method, but also for spiritual healing.

Beyond esoteric Buddhism, Shinto, Onmyodo and Shugendo, these practices found their way into ninjutsu, where they were used depending on interpretation either as a source of genuine supernatural powers, or then as mnemonics for controlling high-stress situations. Because the Kuji-In and Kuji-Kiri so throughly satured the magical side of Japan, they are also frequently referenced in Japanese fantasy fiction. Touhou has several references to the kuji-kiri. Two of these references are rather old, as they appear in Highly Responsive to Prayers and Story of Eastern Wonderland. The nine syllables flash on the screen when Reimu uses her bomb in the game. The kanji also flash when Kongara’s last health bar is depleted. The third reference is Kochiya Sanae’s spellcard Nine Syllable Stabs from Subterranean Animism’s extra stage.