Part of the Suwa Grand Shrine, a venerable Shinto institution that is very relevant to the Lore of Touhou.

Numerous Touhou fans have made a pilgrimmage to there.

Born in Japan in ancient times, formulated from the 5th century onwards, Shinto has been variously described as an animistic religion, tradition or worldview. This is partly because Shinto defies western understanding of religion, lacking a singular founder or definitive body of holy texts. Another part of it is that due to very complex cultural reasons, the word ”religion” has in Japan acquired a meaning almost what ”cult” means in the West. A third factor why some do not see a Shinto as a religion is its extreme focus on doing things rather than belief itself. So while in the West many identify as Christian but never go to the church, in Japan many don't consider themselves religious at all yet attend all the core matsuri (Shinto festivals) and visit the shrines.

Shinto representation in Touhou

Influence from Shinto ideas, beliefs and mythology saturates all of Touhou. Our red and white default protagonist is a shrine maiden (miko) taking care of a shrine (jinja). While in real life the miko mostly work in assisting roles to the priests (kannushi) and perform certain special rituals, Reimu seems to be stuck taking care of the Hakurei shrine by her lonesome. ZUN, curiously enough, calls himself ”the Kannushi of Hakurei shrine”. The two of them apparently have some kind of an unique arrangement where ZUN takes care of shrine business in the outside world and Reimu in Gensokyo.

While miko do not ”exterminate youkai” in real life, youkai in itself are part of the Shinto view of the world. Youkai are strange spirit creatures of ambigious but often fearful and hostile nature. They are often thought to be spirits that could not be successfully appeased or who became irreversibly scorned. The category of youkai is fluid: youkai can turn to kami, kami can turn to youkai, humans can turn to youkai and not all youkai are hostile. And while the miko may not be flinging iron needles or ofuda at youkai in real life, historically Shinto purification rituals were thought to keep youkai at bay.

The Hakurei Shrine is not the only Shinto institution in Gensokyo. There is also the Moriya Shrine, the important characters within there drawing heavily from the lore of the Suwa Grand Shrine, a very real, very old Shinto shrine. The Aki sisters, Hina-sama, Keiki-sama and Chimata-sama are all based on Shinto deities or amalgamations of them. The lore connected to the Moon features many Shinto kami very prominently. Touhou's idea of fairies who are born and reborn with natural cycles and who represent various natural phenomena is also very much in line with Shinto thinking, even if they are not part of the Shinto worldview.

The kami

At the heart of Shinto is the belief in kami, which is a concept with no direct translation. It appears to be variously interpreted as the spirits of things, or just a kind of awe-inducing quality that things possess. In Shinto, there are an innumerable amount of kami: a tree can be a kami, a revered object can be a kami, a human can be a kami, a force of nature can be a kami, and there is even at least one case of a fictional character becoming enshrined as a kami. Some kami are very abstract or local while some appear to be closer to gods in many other religions in how they are portrayed. The Shinto mythology has its share of human-like, but immensely powerful, kami living out drama reminiscent of many other polytheistic religions.

The kami are neither evil or good by nature, but rather have both a gentle and a rough side to them. A rain can water the crops or bring a devastating flood and the sun can sustain life but also destroy it via droughts. In Shinto it is thought that it's possible to cultivate a relationship between humanity and the kami where the kami become favorable to humans. This is done via various rituals, offerings and prayers.

Over time the relationship between humans and kami can become such that it's possible to ask the kami for favors. For example, in real life Tenjin was originally Sugawara no Michizane, an influential scholar and statesman of the Heian period. After his death in exile, he became revered as a kami to prevent him from imposing his wrath beyond the grave. Over time this reverence shifted, and he became to be regarded as patron of scholarship. These days it's very common for students to make offerings and pray to him in pursuit of academic success. In Touhou, Kanako-sama's ambition of becoming a kami of technological progress is perhaps an intentional, self-directed form of this process.

It should be noted that the Touhou canon contains references to some of these anthropomorphized Shinto kami in an unfictionalized way. In particular Silent Sinner in Blue contains numerous references to these kami. These include relatively obscure ones such as Ooguninushi no Mikoto and Izunome, but also very well known ones such as Ame no Uzume no Mikoto and even Amaterasu Oomikami herself. The kami and other ideas to Shinto feature very prominently in Silent Sinner, and there are also entirely unseen and more abstract or monstrous depictions of the kami within there too.

A selection of anthropomorphic kami from Silent Sinner in Blue whom Watatsuki no Yorihime calls to aid her.

Form left to right: Izunome, Ame no Uzume no Mikoto and Amaterasu Oomikami.

Kegare and harae

Doing this veneration of the kami the right way is crucial to Shinto. This veneration includes acts of purification (harae) to remove kegare, a kind of both literal and metaphysical dirtiness. Accumulation of kegare is thought to lead to all kinds of negative things such as diseases, disharmony and bad luck. What exactly kegare is and consists of is difficult to pin down, as it includes both very literal dirt and more metaphysical ”contagion” that is caused by things like misfortune, childbirth and death.

You can accumulate kegare by your own actions, but also by accident. These actions can include essentially harmless things or even positive things (such as getting dirty from work), but also a particular type of kegare called tsumikegare which is accumulated from doing tsumi, a kind of ”sin”. The idea of tsumi includes things like damaging rice fields, certain types of incest, zoophilia and ”skinning an animal backwards” but also things like getting struck by lightning, having tumors and being bitten by snakes. Tsumi leaves an impression that it's mostly things that would have been disruptive to an agricultural society. There are also elements of fear of sorcery and things believed to be infectious such as disease and bad luck in there too.

Kegare is overall a very vague concept, as not only people but also places can accumulate it. It's therefore very fortunate that kegare can be, and is, routinely purified. It should however be noted though that historically certain groups such as lepers, people with tumors and the oppressed burakumin minority were considered permanently impure.

Over time interpretations around kegare have shifted, and there exists a diversity of opinion regarding what exactly it is. Some interpretations are closer to ideas of ”metaphysical impurity”, some see it perhaps in a way as some people speak of ”negative energies”, while some see kegare as something that cuts off people from their original state of being and connection to the surrounding world.

These ideas of kegare and harae are also found in Touhou. In particular, the Lunarians are obsessed with purity and kegare causes them to weaken and age. It was the fact that Earth was so full of kegare that caused them to leave for the Moon in the first place. In Touhou, kegare is described as something that is born from predation, conflict and violence. This also includes entirely natural things such as animals hunting other animals for sustenance. This makes life itself a source of kegare.

One can also find references to Shinto purification rituals in Mountain of Faith. Yasaka Kanako-sama's large shimenawa hoop is likely partly a reference to the large chinowa reed loops used during the oharae, ”great purification” ritual. It's a very important ritual held twice a year, generally during summer and winter. Part of this ritual involves the shrine visitors being given paper dolls known as hitogata. It's thought that the hitogata will take the person's kegare. If there is a body of water nearby, the hitogata are deposited there at the end. This ties this ritual to the character of Hina Kagiyama. She is described as a nagashi-bina, a type of doll associated with another matsuri known as hinamatsuri, but there are similarities between the two festivals. She is also described as creating paper dolls in Symposium of Post-Mysticism, a likely reference to hitogata.

Prayers, offerings and matsuri

After a purification has been done offerings and prayers can be presented to the kami. Offerings depend on the situation and purpose, but include money or food items, most commonly rice, water, salt and sake. After the offering has been made, the kami can be asked for favors. These favors are of worldly nature, health, prosperity for family, success at education or work and finding love. Shinto very intentionaly took on a more worldly approach during the medieval period as a way to distinguish itself from Buddhism.

The kami also enjoy offerings of a kind many in the West would not think about. This offering is the company and joy of humans. This is why the various matsuri festivals form an important part of Shinto. While many Japanese regard these largely as irreligious communal festivities, there is still a core of a ritual at them. The participants of a matsuri at a shrine receive harae and prayers are read to the kami. Often offerings of sake to the kami are also shared with the participants of the matsuri. There's a small number of common Shinto matsuri including saitansai, setsubun and oharae. There are also an innumerable amount of local matsuri held by the various shrines. These local matsuri are known as reitaisai. Coincidentaly or not, there is a also popular annual Touhou fan event in Japan called Reitaisai.

The many forms of Shinto

As one would expect of an essentially animistic belief system, there are a great many local variations of Shinto. It has been presented that there are multiple layers or manifestations of Shinto. These include forms of Shinto centered around the imperial family and the major deities, forms of Shinto centered around worship in the shrines and forms of Shinto practiced outside of the shrines as folk religion. It's very much possible for a person to engage in all of these. There are also a number of discrete sects of Shinto. Some purport to be purist, traditionalist forms that go back to Shinto without external influences, others incorporate practices found in other traditions such as breathing exercises.

This split into layers is also reflected in Shinto beliefs and mythology. It's considered that there are three types of kami: the amatsukami of heavenly realm, the kunitsukami of the earthly realm and the ya-o-yorozu no kami, or ”countless kami” which are everywhere and in every thing. ZUN has stated that in Touhou, the amatsukami live on the Moon. This would make the anthropomorphic kami found in Gensokyo kunitsukami or ya-o-yorozu no kami. This is in line with certain folk religion aspects present in Touhou, such as references to very local deities and the idea of ”native faith”. In one interview ZUN recalls how surprised he was to learn that almost nobody outside of Nagano knew of the deities of Suwa, which were very important to the culture of his childhood surroundings.

Sacred objects and locations

Shinto is very tied to very real, concrete locations in Japan where the kami are thought to reside and be enshrined in. In fact, often the people do not so much revere a kami than rather all the kami in a shrine. While Shinto is practiced in many forms, it's widely thought that a person should revere the kami of at least two shrines: the shrine nearest to them and the Jingu. The nearest shrine (ujigami jinja) is thought to contain the kami that are most directly involved with protecting the individual and the Jingu enshrines Amaterasu Omikami who is thought to protect all Japanese. One can, and often does, revere kami from more than those two shrines. This can be done at the shrines itself, or then one can get ofuda (charms that in some way contain the kami) from the shrines and place them at the kamidana (home altar, ”kami shelf”) at their home.

A very important and particular category of sacred objects – and locations – in Shinto are the go-shintai. These are physical objects which are thought to be able to temporarily house the kami. These objects can be artificial such as gohei wands or shinzo sculptures of kami, but also natural objects such as trees, rocks, waterfall and mountains.

While Mt. Fuji is Japan's most famous go-shintai, the mountain that is the object of worship at Suwa Grand Shrine gave Mountain of Faith it's name. Reimu and Sanae both of course use gohei wands. The idea of go-shintai also most likely influenced the belief in tsukumogami, the idea that beloved items can develop a soul of their own. The Tsukumo sisters and Raiko Horikawa from Double Dealing Character are a reference to this belief. Go-shintai are also very straightforwardly referenced to in Wily Beast and the Weakest Creature, where Keiki-sama is described as creating items that can hold souls. She also offers to create a go-shintai of Reimu, apparently seeing Reimu as being a kami herself.

A very common type of go-shintai are objects modeled after the three treasures of the Japanese imperial family, the sword, the mirror and the magatama jewel. All of thes three are commonly found in shrines, and small mirrors and magatama jewels are often also used at kamidana at home. These items are tied to the legend of Amaterasu Oomikami hiding in a cave and plunging the world into a darkness. The mirror and magatama were used in luring her out, and the sword was given to her by Susanoo-no-Mikoto as a reconciliatory gift. In Touhou, several of Keine Kamishirasawa's spellcards refer to these imperial treasures. The magatama are also featured prominently on Keiki-sama and Misumaru-sama.

An unusual feature of Shinto is that sometimes what exactly is enshrined at a shrine is completely unknown! Several factors contribute to this. The first is that Shinto is simply extremely ancient, and at times records have simply become lost over time. The second is that if the go-shintai is a small physical object, it is wrapped under increasingly layers of fabric and stored in increasing layers of boxes. Over time it's original nature simply becomes forgotten. The third factor is the Shinto tendency to place more focus on the shrines itself, as they can house multiple kami. In Touhou, this is reflected by the Hakurei god being essentially unknown.

Living kami and shamanic maidens

In many shrines the position of a priest is a hereditary position, and only ordained priests or miko can perform many of the rituals. The idea of hereditary priestly lines is present in the Kochiyas, and possibly the Hakureis. Sanae-sama also represents a Shinto idea that ZUN thinks has passed into fantasy, the idea of a human being as a living deity. The most famous example of these living deities were historically the emperors of Japan. After World War II Showa Tenno (Emperor Hirohito) declared that he is not an arahitogami, or a "presently manifest human kami". In Touhou, Keine's spellcards that refer to events related to the imperial family might reflect this aspect of them "passing into fantasy". The imperial family and it's lineage still maintains an important role in Shinto by participating in certain rituals. The imperial family however isn't the only family in Japan thought to have a divine lineage - and ultimately all humans are seen to be children of the kami. Of particular relevance to Touhou though is the fact that one family that is thought to have divine lineage include the priests of Suwa Grand Shrine.

An element of shamanism persists in Shinto. The miko originally filled a shamanic role, going into trance states through intense dancing. One of Reimu's spellcards in UFO is a reference to this, as are the dances she is forced to perform at the end of Cage in Lunatic Runagate. The kagura dances that are performed for the kami are a remnant of this. Some more explicitly shamanic practices persist at the fringes of society to this day.

Local or universal?

Since Shinto is extremely tied to Japan, physical locations there and it's culture, many see Shinto as an indigenous, if not an ethnic Japanese religion that can not effectively or meaningfully be practiced outside of Japan - or by non-Japanese. The shrines in Japan do welcome all people who perform the harae and behave themselves, so it's not exclusionary in that sense. The fact remains that practicing Shinto as an outsider, especially outside of Japan is difficult. For example, a proper home shrine is thought to require ofuda from an ordained Shinto priest. For those interested in practicing Shinto outside of Japan, performing yohai is probably the best option.

There however do exist certain Shinto sects (which some might consider separate religions) that have a more international presence, and for example the network of Inari Ookami worshippers facilitate access to proper kamidana and ofuda even for people outside of Japan. There are also a small handful of Shinto shrines outside of Japan. So perhaps rather than being entirely "ethnic" religion, Shinto requires one to join the community of followers, perhaps as one would expect from such a community-oriented religion. This contrasts with certain "new religions" in the West, which many think of being very individualistic and self-identity based.

However, there have been certain modern movements, minority as they may be, making the argument that there are universal elements within Shinto that transcend the boundaries of nations and even religions. It has been argued that a certain kind of "natural religion", a spontaneous awareness of divine that can be found by observing nature and it's patterns, is at the core of Shinto. This can certainly be cultivated in any place, in any culture. While Shinto is often said to be sparse on ethics, it does encourage sincerity, honesty, dedicated work and gratefulness towards not only other people, but everything that makes human life possible. These too are values that can be cultivated by everybody regardless of place or culture.

Conclusion

The idea of hidden, unknown kami, the rich menagerie of spirits, the way the world itself is seen as being alive and the intense focus on location, lineage and ritual give Shinto a kind of esoteric air about it. At the same time, anyone who partakes in the purification rites, gives an offering and behaves is welcome to visit a Shinto shrine. From the Western perspective, it's a truly unusual mix of the hidden and welcoming, perhaps much like Touhou itself is.

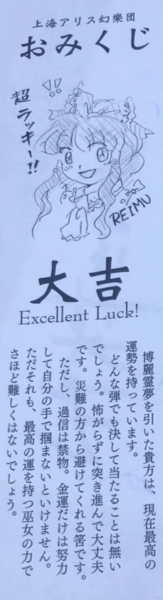

An omikuji, fortune telling paper strip, produced by the Head Priest of Hakurei Shrine himself.

You may draw your own omikuji here!