The Seitenkyuu temple traces it's origins to the mysterious ancient past of 1995.

Taoism was historicaly more of a major influence rather than an organized religion in Japan.

Taoism is a belief system of Chinese origin that incorporates elements of religion, philosophy, medicine, craftsmanship, astrology and magic. It's the third religion present in the world of Touhou. In the outside world, the religious aspects of Taoism have had a much smaller presence in Japan than Shinto and Buddhism. However, the various other aspects of Taoism have had an immense impact on all of East Asian culture, Japanese culture included.

Early Taoist texts largely lacked liturgical elements and explicitly supernatural ontology or references to particular deities. This allowed Taoism to be adapted to different cultures and circumstances, sometimes as a philosophy, sometimes as a set of practices, sometimes as a religion and sometimes as all of this and more. While Taoism is very diverse, common goals in it include self-cultivation, deeper appreciation of the Tao and a more harmonious existence.

History and core ideas

Taoism traces its existence to ancient times. It was born out of Chinese folk religion, shamanism and the observation of natural systems, the workings of the human body and human society. Over time these beliefs and observations became codified into written works. Tao Te Ching is considered the foundational work of Taoism. It illuminates the Taoist worldview and the ideas of the Tao, effortless action and te, virtue. Oldest known portions of it are from the 4th century BCE. This work is attributed to the possibly mythological Laozi, ”old master”. Zhuangzhi is another foundational work, written in the late Warring States period (476-221 BCE). The text seeks to illuminate arbitrariness of dichotomies and praises human freedom and following nature. This text is attributed to Zhuang Zhou. Neiye, from 2nd century BCE contains the earliest known references to Taoist meditation and the various life and spirit energies of qi, jin and shen.

Taoism takes its name from its central concept, the Tao. This term can be translated as ”the Way” In Chinese, it’s still used in its literal meaning to signify “road”. It has been described as the natural order that enables everything to exist and as ”the most abstract concept”. It can be seen as the source of all existence, unnamable mystery, all-pervading sacred presence and the universe as a cosmological process. Tao Te Ching famously opens with ”the Tao that can be named is not the true Tao”. Indeed, the exact nature of this ”dark, indistinct, obscure and silent” idea is thought to be impossible for humans to name or fully comprehend. Instead, the Tao can be observed by observing its myriad manifestations, including the observer themself. It can be seen in the rhythms and patterns of the natural world. Change is seen as the fundamental nature of all things, and it's the Tao that enables and manifests in these changes.

Te, often translated as ”virtue” or ”internal character”, is another important Taoist concept. As most Taoists see human nature as inherently good, this te is thought to emerge from living and cultivating the Tao. Te can include conventional ethical virtue, but also a kind of sagely, spontaneous virtue that comes from wu-wei, effortless action. Action is seen to be effortless when it's not against the Tao, the nature of things. In practice this includes things like letting go of egoistic concerns and forceful, disruptive methods that cause tension. Instead, gentleness, adaptation and ease are to be followed. Taoist ethics treasure effortlessness, naturalness, spontaneity and simplicity. Taoism als has its own ”three treasures” of compassion, frugality and humility.

Taoism's great interest in the observation of nature and the human body led to the emergence of astrology, medicine and meditation. The observation of patterns also gave rise to the concepts and practices we would consider spiritual and magical such as divination and spellcraft. These different fields interlink with each other in ways rarely seen in other systems of spirituality. The ideas of yin-yang, the five Wu Xing phase changes, and the trigrams of the Bagua, the hexagrams of the I Ching and various forms of energy act as conceptual links and correspondences between these various fields. We will explore these ideas closer next.

Emanations, patterns and energies

There are forms of Taoist explanations for the birth of the world that are emanationist in nature, describing how the functioning of the universe in the broadest possible sense, the taiji, proceeds from a kind of infinite singularity to the ”myriad beings” which define the world as we perceive it to be. In the beginning there is wuji, the non-polar all-encompassing infinity. The wuji gives rise to yin and yang, two opposing yet complementary forces that serve as the basis for further patterning of energy, matter and interactions. Yin is associated with things like passivity, retraction, contraction and darkness while yang is associated with their opposite: activity, repelling, expansion and light. These two forces are interconnected and exist in a kind of active, opposing balancing act and can be conceptualized as two polarities of energy, sometimes even called the ”negative” and ”positive” energy. When one of these forces reaches its peak in some phenomena, it begins to dwindle. An easy to understand example would be the fact that after the sun reaches its peak during the day, it starts to set.

Often yin and yang are also thought to represent feminine and masculine qualities, but some strains of Taoist thought see that all humans can manifest either of these qualities. Others see men as having an external yang essence, but an internal ying one, and vice versa. Yin and yang are frequently referred to with the symbol ☯ , but this symbol, instantly recognizable to all Touhou fans, is actually a simple taijitu, taiji diagram, depiction of the universe encompassing both it's dual and monistic features. I will however refer to it as ”yin yang symbol” for the sake of clarity later on.

The interactions between yin and yang are seen to give rise to more refined, divided patterns via a process of transformation and coupling. Yin and yang can transform into each other and be present in different phenomena and objects in different quantities. This makes all kinds of yin-yang combinations possible, which gives rise to the concepts of younger and elder yin and yang, related to the Bagua trigrams. Younger forms of yin and yang possess some of the other, while the elder, mature forms are purer. These are often represented by combinations of two lines, ⚊ unbroken for yang and ⚋ broken for ying. They form the combinations of ⚌ elder yang, ⚍ younger yin, ⚎ younger yang ⚏ elder yin. These four combinations are also known as the Four Faces of God or Four Images of God.

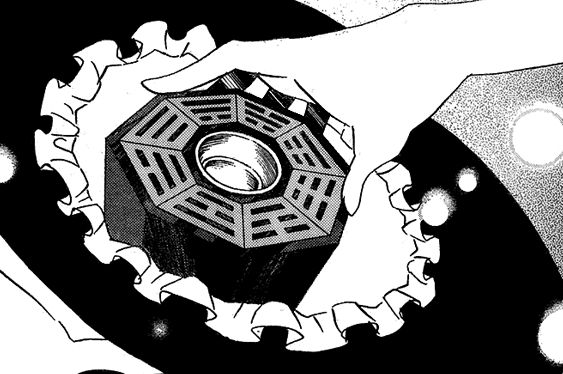

These combinations of yin and yang are capable of self-generation, and when they generate a further ”line”, they give rise to the eight Bagua trigrams formed out of three lines of yin and yang. Bagua can be roughly translated as something like ”Eight Revelations”, and considering their connection to I Ching divination, this translation seems quite apt. These eight trigrams are thought to encapsulate the fundamental nature of all matter. These trigrams are massively important to Taoism and wider Chinese culture, and they have correspondences in astrology, medicine, divination, astronomy, geography, anatomy, arts, feng shui geomancy and martial arts.

The eight trigrams and their associated qualities are:

☰ Heaven – Qián – Expansive energy, the sky.

☴ Wind – Xùn – Gentle penetration, flexibility.

☵ Water – Kǎn – Danger, rapid rivers, the abyss, the moon.

☶ Mountain – Gèn – Stillness, immovability.

☷ Earth – Kūn – Receptive energy, that which yields.

☳ Thunder – Zhèn – Excitation, revolution, division.

☲ Fire – Lí – Rapid movement, radiance, the sun.

☱ Lake – Duì – Joy, satisfaction, stagnation.

These trigrams are traditionally arranged in two different ways: the ”primordial Bagua” or earlier heaven arrangement of Fuxi, and the later heaven arrangement of King Wen. Fuxi was a mythological first emperor of China, who along with his sister-wife Nüwa are attributed with the creation of humanity and giving them many gifts of culture, the earlier heaven arrangement of Bagua included. King Wen of Zhou is an important figure in Chinese history, but for our interests here, he is credited with the creation of the I Ching hexagrams. The later heaven arrangement of the Bagua was revealed to him while he was imprisoned by King Zhou of Shang who was afraid of his growing power.

These two arrangements use the same trigrams, but they are arranged differently and are thought to represent different aspects of reality in the various arts and practices where they are used. The earlier heaven arrangement is arranged using the He Tu mystic square, sometimes called the Yellow River Map because of its association with the myth of Yu the Great who saved China from the Great Flood. In fact, the ”river” of the map is the Milky Way, and it's a map of the constellations. This arrangement is thought to reveal the innate flow of yin and yang, and in Chinese medicine the earlier heaven arrangement refers to conditions that affect one before birth. The Luo Shu mystic square is used to arrange the King Wen later heaven arrangement, and it is thought to demarcate the key patterns of change of yin and yang. By knowing this arrangement, the sage could have control over the four directions, the four elements and space and time. In traditional Chinese medicine, this arrangement refers to conditions which affect one after birth.

As mentioned before, King Wen of Zhou is attributed with creating the I Ching hexagrams by stacking the trigrams of Bagua while in imprisonment. The I Ching is richly deserving of an entire section of it's own and I will not delve too deeply in there. It has been used as a practical divination tool, whether it be in the hands of ancient sages or folk fortune tellers, but also used as a form of moral guidance and even enjoyed as literature in itself. The I Ching consists of 64 stacks of six lines, hexagrams, and each of them is associated with a short narrative. These narratives can be thought of as a kind of a stock of archetypes of events. The hexagrams too can transmute from one to another, and it's thought that this process of transmutation reveals much in the context of divination.

Before we move on to the five elements, it's quite worth noting that this system of constructing increasingly elaborate information from binary alterations has some similarities with modern binary code representations of information. Some have even drawn parallels between the constituent parts of human DNA and the Four Images of God combinations of yin and yang lines. The idea of the universe being patterned around alterations of yin and yang gives rise to a kind of cyclical, spiral-like view of the world. In many ways this is simply factually true – the natural world goes through cycles and growth and decay, and human societies too seem to follow patterns that may not repeat exactly the same seem like elaborations on old themes. It's also remarkable how common spiral structures are in nature, up to them being a rather common galaxy shape.

We finally arrive at the five phase changes, Wu Xing, sometimes also called the Five Elements. The Wu Xing are sometimes thought to represent five phases of change energy undergoes as it transforms into matter, and sometimes it's thought to encompass more physical characteristics too. Overall, what divides it from the Western idea of elements is that it's concerned with process and quality rather than substance. ”Tree” is not literal trees, it's rather ”the quality of trees” such as growth and flexibility that is also found in other things.

The Wu Xing originally referred to the five planets of the Solar system visible to the naked eye (Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars) which along with the Sun (yang) and the Moon (yin) were seen as creating the five forces of life on Earth. From there it became generalized and abstracted into the five phase changes.

The phase changes and some of the features and correspondences attributed them are as follows:

Wood – Growth & Renewal – Jupiter – ☳ Thunder & ☴ Wind – Spring – East.

Fire – Expansion & Assertion – Mars – ☲ Fire – Summer – South.

Earth – Equilibrium & Stability – Saturn – ☶ Mountain & ☷ Earth – Intermediate - Center.

Metal – Harvesting & Gathering – Venus – ☰ Heaven & ☱ Lake – Autumn – West.

Water – Contracting & Retreating – Mercury – ☵ Water – Winter – North.

The Wu Xing can further be divided into yin and yang versions of each other, and each of the Wu Xing have a rather long list of correspondences in the various fields where they are utilized, be it medicine, astrology, geomancy, martial arts... Listing all of them here would make this rather long section much longer. The things of interest to note here is how heavily reliant Taoist and the broader Chinese thought is on various correspondences, and how Fire and Water phase changes are both associated with singular trigrams. While this might seem just an annoying asymmetry to some, I suspect it has something to do with the role of Fire and Water in Chinese mythology and spirituality. It was the clash of gods of fire and water that caused the great flood and forced the reconstruction of the world.

Before we move on, there is one last important feature of the Wu Xing. They are thought to exist in a variety of cycles, the most commonly known ones being the inter-promoting and weakening cycles. In the inter-promoting cycle, wood feeds fire, fire produces earth, earth beats metal and water nourishes wood. In the weakening cycle, wood depletes water, water rusts metal, metal impoverishes earth, earth smothers fire and fire burns wood. This underlines the dynamic nature of the system – it really is a process of change. Furthermore, in the various fields where the idea of Wu Xing is applied, it's thought that deficiencies in certain areas can be supported by bringing in things with qualities from the supporting cycles. For example, if an astrological analysis revealed Fire as the birth phase, but the person had a lot of other factors and circumstances dampening this phase, one could bring in things with wood-qualities to ”fuel” this birth phase of fire.

The interplay of the five phase changes and how energy becomes patterned via them gives rise to the ”myriad things” that is the final step in Taoist emanationist thought. These myriad things are all the separate things that we perceive as making up the universe as we know it.

But what is this energy that gets patterned in this increasingly complex process? The Taoists would call it qi. It literally means ”vapor”, ”air” or ”breath”. Broadly speaking, qi is seen as the fundamental thing that makes up the universe and all the things in it, and back to which all the things eventually dissipate into. It's thought that as qi becomes patterned by the processes of patterning and change, its fractions acquire different characteristics such a coarseness or heaviness. The most ethereal fraction of qi was thought to be the qi that gave life to living things.

It's indeed this qi of life that is perhaps most well known, and within Taoist thought, this qi is divided into various forms of qi. There is the primordial qi, acquired from parents, the qi of air, the qi of food... The human body in general is seen as having both corporeal and incorporeal aspects, organs and parts, elixir fields, inner substances, animating forces and energy channels. Beyond qi we also have shen, which is a spiritual force that is responsible for power, agency and capacity to connect with the spiritual aspects of reality. There is also the jing, which is a kind of personal life force, some of it acquired from parents at birth, some of it acquired later in life via metabolizing qi. Jing is continuously consumed by everyday life, and can be consumed in excess by things like stress, illness, substance abuse and excessive sexuality.

A wide range of practices aimed at cultivating, purifying and alchemizing these life energies developed around Taoist thinking. These practices are known as qigong, internal arts and internal alchemy. They range widely in aims and qualities, from the accessible to extremely demanding and esoteric. It's thought that it's possible to improve health, extend life and even cultivate supernatural talents and a form of consciousness that can survive bodily death using such techniques. Ideas derived from Taoist thought regarding the life energies and qi have also made their way into the ”hard”, external arts, or martial arts as they are more widely known.

Sic Mundus Creatus Est, as the ancient Westerners would have said.

These elaborate conceptualizations of energy and its patterning and the correspondences that follow also form the basis for the rich Taoist spiritual and magical traditions. Taoist thought shares the idea of microcosm and macrocosm with Western esoteric thought, the idea that there are aspects in humans that correspond to the external world and vice versa. This leaves open the possibility of using indirect means to influence both things happening in the external world and within humans through processes that alter the flow, quantity and patterning of energy.

These emanationist ideas have sometimes been represented as a historically process of elaboration that would almost in a way mirror the emanation itself. First comes the idea of the Tao. Then the ideas of how the Tao manifests in the world became more and more elaborated upon over time. First came the yin and yang, the two cosmological opposing principles which nevertheless are interconnected in a self-perpetuating cycle. From this interplay of yin and yang emerged the five wu xing phase changes and the eight symbols of the Bagua system. The trigrams of the Bagua system were put into use in the I Ching system of divination. All of these linked to Taoist astrology. Magic and medicine emerged and observation of the self became meditation. These practices found their most extreme expression in the pursuit of immortality, be it a literal elixir or a spiritual process of change.

However, historically it seems that things like the Bagua and Wu Xing were initially separate systems that only later – and not perhaps quite perfectly, as we see from the Wu Xing – Bagua correspondences – became unified into a framework. Up to this day, there are disagreements when it comes to certain correspondences, and the most popular emanationist taijitu model is based on the model created by Zhao Huiqian in the 1370s. Still, it's quite remarkable how well the system fits together, and how Taoism has produced, if nothing else, a symbolic language capable of linking together seemingly extremely disparate fields. It's also interesting to note that many other traditions have independently developed emanationistic models for the functioning of the world. But in Taoism, rather than it being a process of degradation, it's a process of elaboration.

Influence of Taoism on Japanese culture

Taoism arrived into Japan around the 5th century, when Japan started to seek outside influences to enrich the cultural life of the country. It arrived alongside Buddhism and Confucianism. Where Buddhism would go on to become a major religion and Confucianism impacted the political and social culture, Taoist ideas had a very wide, diffuse influence on culture. With Taoism came philosophy, traditional Chinese medicine, astrology and knowledge on various crafts and magic associated with it. These ideas strongly influenced both the cultural elite as well as became part of various folk beliefs over time.

The arrival of new ideas of Chinese origin forced the Japanese to articulate their own native ideas, and this led to the birth of the idea of Shinto. With no previous other religions present, there had been no need to name the religious practices present. The process of codifying Shinto included the emergence of texts such as Kojiki and Nihon Shoki which for the first time contained Shinto mythology and legends in a written form. The potential influence of Taoism can be seen in these accounts. There is yin-yang symbolism present, and the kami responsible for the creation of the world are associated with the Big Dipper, as are the creator gods associated in Taoism. We will return to the notable part the Big Dipper plays in Taoism later.p>

Onmyodo, Shinto-Taoist syncreticism

Taoism and Shinto found a fruitful synthesis in the onmyodo magic. One part of the cultural importation process was the establishment of the ”bureau of yin and yang”. The onmyodo were mages influenced by various Taoist ideas who worked there. The observance of various calendrical taboos and geomantic practices formed a big part of what they did. One can find onmyodo in scattered pieces within Touhou.

Chen and Ran are notable examples, as they are described as being shikigami. The concept of shikigami came from onmyodo. They are conjured spirit entities that fulfill the role of familiars. They are often tasked with doing things that are too risky for their master, such as spying or stealing. The shikigami are directly connected to the spiritual force of their master. Skilled masters can have shikigami which are capable of possessing animals or even people. On the other hand, there is a risk of shikigami developing a will and personality of their own and getting out of control and even killing their own master. This is reminiscent of the Tibetan tales of tulpas.

Hakurei Reimu is said to be trained in onmyodo magic, which she uses in her job as a youkai exterminator and conflict resolver. While Reimu is a miko, a part of a Shinto institution, her powers as described in the print works actually veers very close to Taoist thought. She can ”float over life”, which manifests as her being nearly unstoppable and capable of avoiding grave danger as long as she sticks to the right path. However, she constantly finds herself distracted by selfish motives and loses her edge. One can't of course forget the most obvious Taoist symbol present in the game, the ubiquitous taijitu, or yin-yang. Touhou frequently uses a white and red version of the symbol. These colors are considered lucky in Japan. These colors are also widely seen as symbolizing chthonic and celestial forces.

If Reimu is a Shinto character using Taoism-influenced magic, the Mononobe no Futo is a Taoist character using magic influenced by Shinto. While she uses the Taoist art of feng shui, geomancy based on the idea of directing the flow of qi, her spellcards refer to various Shinto myths. Perhaps she is invoking some other power than qi via the kami? Or maybe she uses qi to power her spells and the references to Shinto mythology are tools for shaping how the power will manifest?

While Mononobe no Futo is not described as an onmyodo, her outfit is based on the classical depiction of the outside world Onmyodo. This and the colored ribbons, referring to the idea of Wu Xing phase changes, are a strong visual reference to her Taoist affiliation. She is described as being a shikaisen, a type of an immortal who has cheated death by substituting an enchanted object for her corpse. In her case it's said to be a plate.

Toyosatomimi no Miko's Taoist clique in Touhou

Futo is a member of the Taoist clique surrounding Toyosatomimi no Miko. They are the most identifiable expressions of Taoism within Gensokyo. Miko herself is based on the historical prince Shotoku, who historically was a scholar and a prince who greatly advanced the Buddhist cause in Japan. He was also well-versed in other forms of Chinese learning, which would have included Taoism.

In Touhou, Miko had hatched a plot where the social elite would have followed Taoism, and the people would have been following Buddhism as a form of social control. This might be commentary on the popularity of Taoist practices among the court and the influence that Taoism had on the development of East Asian Buddhism. Miko, like Futo, is also a shikaisen. Her object of choice is a sword that is a type of Taoist ritual sword that we will return to later. Miko's in-game appearance is a reference to a legend where she could understand ten conversations at once. ZUN also wanted to give her a striking, modern appearance because the image of historical prince Shotoku is so established.

Soga no Tojiko is a failed shikaisen, whose attempt at reaching immortality was foiled by Futo. The Mononobes and Sogas were historically enemies, so this reflects the real history of conflict. Her powers of thunder are partly a reference to a type of Taoist exorcism known as Thunder Rites. The idea that vengeful spirits can cause thunder is also present in Japanese culture. She's an example of ZUN finding parallels in ideas from different traditions.

Seiga Kaku is the teacher of the Taoist clique. She is described as being a ”wicked hermit” who practices a self-centered, sociopathic interpretation of Taoism. There have indeed been some very individualistic, even anarchistic interpretations of Taoism. The idea of spiritually powerful hermits is a prominent idea in Chinese culture. There is a strand of Taoist thought which sees almost all human activity taking place within the context of an organized society as complicating and corrupting. The world of humanity is filled with all kinds of desires, distractions and temptations which can drain one's energies. Many Taoist mystics thus historically secluded themselves to minimize external interference and to be closer to nature, and over time a system Taoist monasteries formed. In some Taoist traditions Laozi himself is seen as having been a hermit.

Seiga's spellcards feature many esoteric Taoist concepts, including yang xiaogui (use of dead spirits as tools), guhun yegui (abandoned wild ghost), zouhou rumo (a frenzied state caused by mismanagement of vital energy), tongling (spirit linking) and tongjing (a ritual where a person gets possessed by a divine spirit). Her ”Dao Fetal Movement” has sometimes been interpreted as use of aborted fetuses, but it might also be related to the idea of cultivating a kind of ”spirit embryo” in some Taoist immortality techniques.

It's impossible to speak of Seiga's presence in Touhou without speaking of Miyako Yoshika, who is Seiga's servant and a jiang shi. The jiang shi are a type of Chinese zombie. While the Taoist clique outside of Seiga at the very least tolerates her presence, real life Taoist religious institutions dread the undead so much that jiang shi cosplayers are not allowed on temple premises.

Wu Xing, Bagua and Qi in Touhou

The Taoist clique might be the most prominent representation of Taoist ideas in Touhou, but they are not the only one. Beyond Futo's geomancy, the Wu Xing system is also referred to elsewhere in Touhou. Patchouli Wisdom is described as an ”Eastern style Western magician” who uses these phase changes as one would use the fantasy interpretation of Western elements in her elemental magic. Patchouli can also use the ”elements” of Sun and Moon, a double reference to the celestial origins of the Wu Xing and the fact that weekdays in Japan are named after the Wu Xing and the Sun and Moon.

There are also references to the Bagua system trigrams and the I Ching hexagrams derived from them in Touhou. The most prominent use of them is Yukari Yakumo's tabard, which has the trigrams for Lake and Earth. Together these form the hexagram ”Ts'ui”. It has the meaning of gathering together to persevere for a goal. This hexagram also signifies great wisdom which is necessary for leadership when directing an assembly together to create overall prosperity for everyone. Whether one thinks of Yukari, this is certainly a hexagram that someone who sees herself as the overseer of Gensokyo would like to display.

Another character whose outfit incorporates the trigrams is Eirin Yagokoro. Her skirt features the trigrams for Heaven, Wind, Fire, Mountain, Earth and a sixth one which is obstructed. What this sequence is meant to communicate is up to your interpretation. Is it a sequence of changes? Three hexagrams waiting to be stacked?

The trigrams of the Bagua are often arranged in an octagonal pattern. Marisa Kirisame’s Mini-Hakkero, the miniature alchemical furnace she uses for spellcasting, is patterned after this arrangement. In fact, the name translates into something like “Mini Eight Trigram Furnace”. Taoist alchemy, both internal and external, uses the Bagua trigrams as conceptual tools, which is likely why she has a tool like this. Another instance of the full octagonal arrangement of the Bagua trigrams making their appearance is Hakurei Reimu’s sigil in Touhou Hisoutensoku. It’s depicted in the primordial Bagua of Fuxi arrangement.

Another reference to the Bagua is how Kanako-sama and Suwako-sama are described as being able to create ”heavenliness” and ”earthliness”. These are a reference to the Bagua trigrams of Heaven and Earth, and their corresponding I Ching hexagrams. The Heaven, Qián, is an active, pure yang force while the Earth, Kūn, is a receptive, pure yin force. These Heaven and Earth have a particular lore in Taoism and wider traditional Chinese beliefs. They are thought to be two of the poles that maintain the three realms of reality. These three realms are the Heaven of the celestial deities, the middle realm of humanity and the chthonic underworld of Earth occupied by ghostly and demonic entities. Rather than being opposed, Heaven and Earth are complementary forces, and themes of the union of the two maintain a very central role in Taoist spirituality.

A considerably more obscure character featuring the trigrams is the ”Moonlight's Anti-Soul” Hourai Girl. The Hourai Girls were a series of characters that ZUN drew between the PC-98 and Windows era Touhou games, which share design features with later Touhou characters. Miss Moonlight's Anti-Soul has the trigram for Water on her chest, fitting her association with the Moon. On her cap she has the trigrams for Wind, Earth and Fire. While not perhaps Taoist per say, the name Hourai comes from Chinese myths about an island of immortals somewhere in the Eastern seas. Later Japanese re-interpretations gave it a considerably less paradisiacal interpretation, painting it as a cold island inhabited by fairies.

A final and slightly tenuous potential reference to Bagua is the name of the fifth Touhou game, Mystic Square. While all sorts of mystic and magic squares are featured in many different cultures, the He Tu and Lo Shu squares would be the ones closest to Japanese culture.

Touhou doesn't have many explicit references to qi, but the character Hong Meiling is described as being able to manipulate qi. She uses it in a way that is very consistent with other fantasy depictions of martial arts, projecting it outwards to attack her foes. These are based on real-life ideas about how powerful enough cultivators of chi can use it to perform tele- and pyrokinetic feats. Of some interest is that in Perfect Memento in Strict sense, Akyuu describes the ”strange slow dance” a villager saw Meiling performing as Tai Chi Chuan. This is the internal martial art more commonly known as Tai Chi in the West. While Tai Chi is on the least esoteric end of the internal arts, the belief in qi and how Tai Chi can improve its functioning within the human body forms part of its traditional worldview.

The Seven Stars

Touhou has several references to an extremely important part of Taoist theology, namely the part of the night sky which is thought to be the physically manifest part of Heaven. This is the Northern skies, and in particular the North Star and Big Dipper. In Taoism and various forms of Chinese traditional religion, The Big Dipper is thought to be the throne of the supreme deity, Shangdi. Shangdi himself is associated with the North Star. The origins of this belief can be traced back at least to the Shang dynasty, roughly 2000 years ago. In certain Taoist beliefs the Big Dipper is also associated with the creation of the universe, and this might have influenced the Japanese creation myths. It's also possible that the similarities reflect even older shared Ancient North Eurasian or Austronesian cultural heritage.

The Big Dipper's role in Taoism can be roughly split into four categories:

1) The Big Dipper indicates the proper direction for performing rituals or meditation through the movement of its ”handle” through the year. In the earliest forms of the Chinese calendrical system, the Big Dipper was the ”timekeeper” whose rotation determined the seasons.

2) The Big Dipper is believed to open the way to heaven via it's seventh star, Tianguan, Heavenly Pass, in rituals and meditation.

3) The Big Dipper is a recipient of invocations of forgiveness for one's sins and to have one's name erased from the ”registers of death”, siji.

4) The Big Dipper is believed to have strong exorcistic powers due to it being a divinity of the North, but also the underworld. The direction of the Big Dipper orientation determines from which direction the thunder is summoned in the exorcistic Thunder Rites.

As one can imagine from this multitude of roles, the Big Dipper was considered to be of utmost importance and vast power. Thus many practices for invoking its might came to be developed. An example of these are the Bugang rituals, a form of Taoist ritual dance. In one version of these rituals, the practitioner paces through a pattern made in the likeness of the Big Dipper. Many great benefits are thought to arise from this practice: the ability to avoid blame, weapons and death itself and command over vast spiritual powers and the ability to reach out to the gods.

As mentioned earlier, Toyosatomimi no Miko's shikaisen object is called a sword. This sword in question is a Seven Star Sword, which is a class of Taoist ritual swords that very much exist in real life too. The Seven Stars are of course a reference to the seven stars of the Big Dipper. She also has a spellcard named after these swords.

The much more visible bearer of the Seven Stars in Touhou is the Secret Ultimate Hidden God Matara Okina-sama. While her design is largely based on the highly ambiguous, most likely syncretistic medieval Buddhist and Shinto deity Matarajin, her depiction has number of features that link her with Taoist ideas regarding the Big Dipper. Whether these are merely due to the syncretic nature of Matarajin, ZUN wanting to make subtle nod towards Taoist ideas or some other form of inspiration is unknown. The most explicit nod towards Taoism in her case is the fact that she too has a spellcard refering the Seven Star Swords.

Okina-sama's involvement in the creation of Gensokyo is likely a reference to the Japanese and Chinese mythologies about the Big Dipper and deities dwelling there being involved in the creation of the world. Matarajin, for all his roles, was not thought to be a creator deity. It's also noteworthy that the plot of Hidden Star in Four Seasons involves abnormalities of the seasonal cycle – something that the Taoists, among other cultures, associated with the Big Dipper.

Another possible Taoist influence of her origin and depiction is how Shangdi was portrayed in Chinese culture – or rather lack of it. Shangdi was thought to be more transcendent than immanent, too distant for ordinary people to reach out to, and instead working his will through the hierarchy of lesser deities he lords over. Shangdi wasn't ever represented with direct iconography either. This would be fitting of a ”Secret Ultimate Hidden God”.

The potential Shangdi connection is strengthened by the fact that in Chinese culture it was thought that Shangdi also had a female manifestation. This manifestation is known as Doumu, ”Mother of the Big Dipper”. In esoteric Taoism she is equated with several powerful figures, including the powerful hero Jinling Shengmu, Jiutian Xuannu who is a goddess of war, longevity, magic and sex, and Xiwangmu, Queen Mother of the West, who is a goddess with a paradisical palace that has an orchard of peaches of immortality. If such powerful syncretisms and associations were not enough, the Buddhists also associated Doumu with the deity and boddhisattva Marici. Of Marici's depictions most interest here are the Japanese ones as Marishiten, where she was associated with light, mirages and invisibility.

Okina-sama's two companions who come from Matarajin being depicted with two douji are likely of Taoist origin too. In Taoist belief, it's thought that the Big Dipper actually has nine stars, but two of them are invisible. This is a likely origin not only for Matarajin being depicted with two douji, but also the reason why Doumu is thought to have two sons. Marishiten too was thought to have two companion deities, but of more equal terms. One of the rewards from diligently performing the Bugang ritual was believed to be the companionship of ”divine lads”, which ”douji” have sometimes been translated as. It's also quite noteworthy to state here that while the Big Dipper was thought to be the throne of Shangdi, the deity itself was frequently associated with the Pole Star. This is very remarkable for the topic at hand for the reason that Polaris is actually a trinary star system. The ancient Chinese, as far as I know, would have lacked the kind of telescopes required to perceive the two smaller companion stars...

As for the powers of manipulation of ”life energy” and ”mental energy” that Okina-sama is depicted as having in Touhou, there is a likely Taoist connection there too. As stated before, the cultivation and manipulation of various vital and spiritual energies is of interest to Taoist practice, and these too have a connection to the Big Dipper. The direction towards which the Big Dipper points to is known as the Gate of the Vital Force, or mingmen. Because the Chinese too believed that as above, so below, this mingmen is also found in the human body, between the kidneys as an acupuncture point. It's thought to have an important role in the energetic ”metabolism” of the human body. Here it might also be noteworthy to say that it was thought that Doumu was the mother of the immortal ”red infant” within humans. This cultivation of this embryonal spirit into a soul capable of surviving physical death is the goal of internal alchemy aimed at attaining immortality.

One final note is related to the depiction of Okina-sama as a god of the crippled. The Bugang ritual is a part of a class of rituals known as Yubu. These rituals involve a dance – by now you had probably forgotten Okina-sama is also associated with the performing arts... – in which the performer drags one foot after another. This is a reference to Yu the Great, an ancient legendary king of China who crippled himself through overexertion while he was restoring order after the Great Flood.

Conclusion

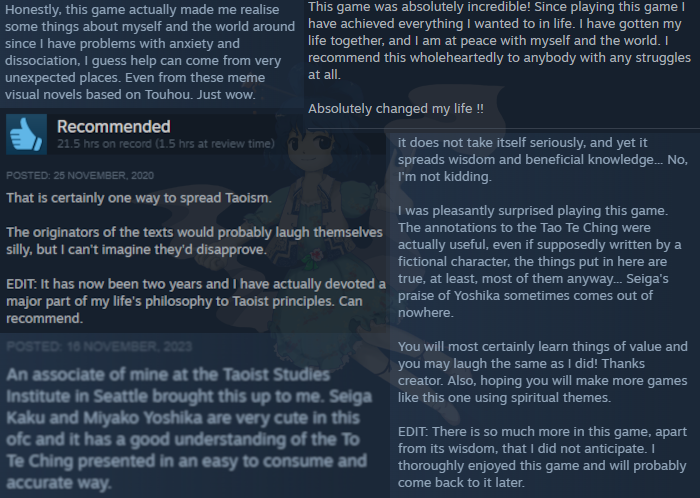

Overall, Touhou, much like East Asian culture, is rife with Taoist ideas. In particular Touhou highlights some of the more fantastical, stranger aspects of Taoism that get overshadowed by things like tai chi and acupuncture in real life. Overshadowed as they may be, these aspects of Taoism have refused to pass into fantasy. You are only one YouTube rabbithole away from stumbling into Taoist sorcery being practiced to this day, here in the outside world. For those who are interested in less fantastical things, Taoism offers a fascinating philosophical system that challenges common assumptions – including assumptions about East Asian culture.

Even slight exposure to Taoism can be life-changing.